Matala’s Historical Context and Counter-Cultural Emergence

Matala’s ancient significance

Located on the southern coast of Crete, the village of Matala has a history that extends beyond its known 20th-century counter-cultural phase. In ancient times, its natural harbor was an important port for the Minoan city of Phaistos, for trade and maritime activities during the Bronze Age. This coastal position maintained Matala’s importance through different historical periods, connecting it to Cretan and Mediterranean civilization long before it became known for a bohemian lifestyle.

The most notable features from Matala’s ancient past are the many caves carved into the sandstone cliffs around its bay. Although these caves are often associated mainly with their 1960s inhabitants, they originated in the Roman era. During this period, the caves were excavated and used mainly as burial sites – tombs for the dead. This earlier use of the caves is very different from their later use, but it is an important part of the long and varied history of this Cretan place.

Setting the stage for the 1960s.

After its earlier importance, Matala was a traditional Cretan fishing village for many centuries. However, by the mid-20th century, particularly in the 1950s, the village’s landscape and its seclusion began to draw different visitors. Small groups of early individuals seeking lifestyles different from the mainstream, often linked to the Beatnik movement, came to Matala and used its ancient caves for basic shelter. This initial arrival of people was an early sign, preparing the way and giving Matala a quiet reputation long before the larger 1960s international counter-culture movement found and changed this remote Cretan area.

The Matala Commune: Life and Culture in the 1960s Hippie Haven

Establishment and Foundational Characteristics

Matala underwent a significant transformation in the 1960s, as its ancient sandstone caves became the focal point for an emerging international hippie community. The principal attraction was these unique, man-made grottoes, historically Roman tombs, which offered free, unconventional shelter and symbolized a departure from modern materialism. This phenomenon did not arise in isolation; Beatniks had reportedly frequented the caves in the 1950s, and a local Cretan counter-culture had also been noted, laying a nascent foundation for alternative lifestyles. The community’s growth was largely organic, propagated through word-of-mouth within burgeoning counter-cultural networks. Matala became an informal yet recognized stop on the “hippie trail,” its reputation evidenced by anecdotes of travellers being directed with phrases such as “Sheepy, sheepy, Matala, Matala,” indicating its established presence in the counter-cultural geography.

Drawn by this growing renown, a diverse cohort of predominantly young individuals from Europe and North America converged on Matala. These arrivals, often characterized as free thinkers, artists, and travellers, were typically disillusioned with the prevailing social conventions and consumerist values of their societies of origin. In Matala, they sought freedom, peace, and a communal existence, perceiving the village’s unspoiled natural environment and the rudimentary conditions of the caves not as deterrents, but as integral to their liberation from societal constraints. The international composition of this community, uniting varied backgrounds and experiences, became a defining characteristic of Matala’s distinctive hippie enclave.

Daily Life, Artistic Expression, and Communal Hubs

Daily existence for the cave dwellers in Matala was a conscious renunciation of mainstream materialism, characterized by a spartan lifestyle deeply intertwined with the natural surroundings. The rhythm of life revolved around simple pursuits: sunbathing, swimming, exploring the coastline, and engaging in communal activities. While some attempted subsistence living, the nearby village provided essential amenities, including groceries and a bakery whose fresh yogurt and bread became dietary staples. Despite the primitive setting, practical needs were sometimes addressed through collective efforts, such as the reported installation of a diesel pump for water. This pursuit of an untethered existence was not without its challenges; Joni Mitchell, a notable resident, provided a nuanced account, acknowledging the “often rough” realities of cave life, such as hard sleeping surfaces and fleas, an austerity that likely reinforced the commitment of those who chose to remain.

Artistic expression formed the cultural core of the Matala community, with music holding a particularly central role. Evenings were frequently animated by the sounds of psychedelic rock played on battery-powered turntables or the shared melodies of guitars around beach bonfires, an atmosphere Mitchell captured in her lyrics describing “that scratchy rock and roll, beneath the Matala Moon.” Her own musical contributions, often featuring the Appalachian dulcimer, were significant, and informal gatherings like the “Matala Hippie Convention” in April 1970 underscored music’s vital function in fostering communal spirit. Visual arts also found expression, with cave walls serving as canvases for paintings, some reportedly utilizing glow-in-the-dark paints, thereby integrating art directly into their unconventional living spaces, though much of this work was inherently ephemeral.

Beyond the individual caves, local establishments such as the Mermaid Café, operated by Stelios Xagorarakis, evolved into crucial social epicenters. This café transcended its function as a mere refreshment stop, becoming a “kind of headquarters” where the community congregated, exchanged ideas, and forged connections. Its importance was immortalized in Joni Mitchell’s song “Carey,” written for fellow cave-dweller and café worker Cary Raditz. The critical role of such hubs was starkly highlighted in 1969 when the Mermaid Café was forcibly closed, an act that dismantled a key social institution of the Matala scene and presaged increasing external pressures. These intertwined elements—communal living, artistic fervour, the influence of key figures, and the reliance on local meeting points—collectively defined the unique character of Matala’s 1960s counter-cultural zenith.

The Spread of Reputation and Its Profound Impact

Matala’s reputation as a unique counter-cultural haven spread through both informal networks and significant media exposure, fundamentally altering its trajectory. Word-of-mouth, exemplified by the “Sheepy, sheepy, Matala, Matala” directive, initially guided like-minded individuals to the remote Cretan village, fostering its organic growth as a stop on the “hippie trail.” This informal dissemination established Matala within the counter-cultural consciousness before it gained wider recognition.

Matala’s reputation as a unique counter-cultural haven spread through both informal networks and significant media exposure, fundamentally altering its trajectory. Word-of-mouth, exemplified by the “Sheepy, sheepy, Matala, Matala” directive, initially guided like-minded individuals to the remote Cretan village, fostering its organic growth as a stop on the “hippie trail.” This informal dissemination established Matala within the counter-cultural consciousness before it gained wider recognition.

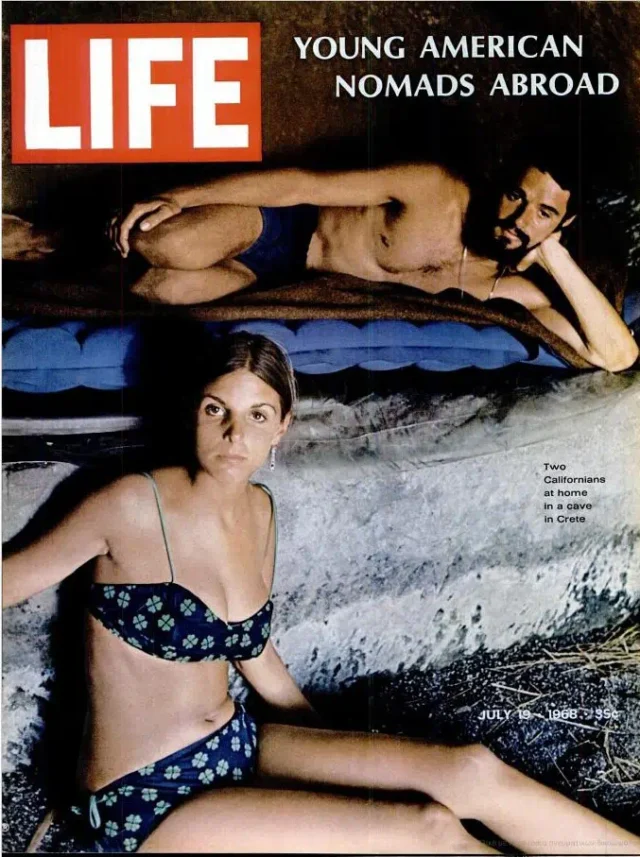

A pivotal moment in the amplification of Matala’s fame occurred with the publication of an article in Life Magazine in July 1968. This feature, titled “Young American nomads on Crete,” complete with evocative photographs by Denis Cameron, brought the secluded cave community to widespread international attention. The article profiled several individuals, offering a glimpse into their unconventional lifestyles and instantly transforming Matala from a relatively obscure sanctuary into a publicized “hippie destination.”

The impact of this heightened visibility was immediate and multifaceted. It triggered a significant surge in visitors, as individuals inspired by the romanticized portrayal sought to experience the Matala lifestyle firsthand. This influx, however, began to strain the informal structures of the community and the limited resources of the small village. More critically, the international spotlight brought Matala under the sustained and intensified scrutiny of Greek authorities. The once-overlooked enclave became a conspicuous symbol of non-conformity, attracting official concern that would contribute significantly to the pressures leading to the eventual dissolution of the original hippie commune. Thus, the very fame that cemented Matala’s legend also sowed the seeds of its transformation and the end of its initial freewheeling era.

The Decline and Dispersal: Societal Tensions and Authoritative Intervention

The period marking the decline and eventual dispersal of Matala’s hippie community was characterized by escalating societal friction and decisive intervention from Greek authorities, driven by a complex interplay of cultural, religious, and political pressures.

Growing Friction with Local Cretan Society

While initial interactions between the hippies and local Cretan villagers were reportedly marked by a degree of “warm welcome and hospitality,” this relationship deteriorated over time. As the hippie population grew and their presence became more entrenched, fundamental cultural incompatibilities surfaced. The unconventional appearance, behaviours, and lifestyle of the “flower children”—including public nudity and perceived moral laxity—clashed profoundly with the conservative, traditional values of the rural fishing village. What was seen as liberating self-expression by the newcomers was often perceived as disrespectful or morally corrosive by segments of the host community. This divergence in worldviews fostered resentment and a local backlash, contributing to calls for the hippies’ removal and illustrating a deep-seated cultural friction.

The Influence of the Greek Orthodox Church and the Military Junta

Two powerful institutional forces played pivotal roles in the demise of the Matala commune: the Greek Orthodox Church and the military junta (1967-1974). The Church, a deeply influential body in Greek society, viewed the hippies’ alternative spiritualities, emphasis on free love, and perceived hedonism as a significant moral threat. Sources suggest the Church actively “spurred and organized” local opposition and lobbied the ruling junta for the hippies’ expulsion, leveraging its considerable influence, which was particularly strong during this period.

The broader political landscape was defined by the military junta, a right-wing dictatorship inherently opposed to the non-conformist and anti-authoritarian ethos of the hippie movement. While initially adopting a cautious stance, possibly due to concerns about international perception and the economic benefits of tourism, the junta’s tolerance waned as Matala’s fame grew. Mounting pressure from locals and the Church, coupled with increasing reports of drug use and perceived moral decay, alongside the junta’s own ideological opposition to such displays of libertarianism, created an environment ripe for intervention. The perceived disorder in Matala eventually became too conspicuous for the regime to ignore.

Official Actions and the End of an Era

The confluence of societal pressure and institutional opposition culminated in direct official actions to dismantle the Matala hippie community in the early 1970s. The authorities’ approach shifted from relative laissez-faire to increasing harassment and intervention. Police raids on the caves became more frequent, often justified by concerns over drug use but also enforcing conventional social norms. The pressure extended to local businesses perceived as supportive of the hippies, exemplified by the 1969 arrest of Stelios Xagorarakis, owner of the Mermaid Café, and the subsequent forced closure of his establishment, a key social hub.

The definitive end to the original hippie occupation came with a comprehensive crackdown. Police forced all hippies to vacate the caves, which were then officially closed to habitation, with entrances reportedly fenced off with barbed wire to prevent reoccupation. This final expulsion was carried out by the junta authorities, reportedly at the explicit request of the regional bishop, underscoring the collaborative pressure from state and religious institutions. Some hippies were arrested, while others were compelled to relocate. By the 1980s, the Greek state further regulated the area, declaring Matala a protected archaeological site, formalizing the prohibition of residing in the caves and marking the conclusive end of its celebrated hippie era.

Contemporary Matala

Matala Today: Remembering the Past, Living in the Present

After the hippies of the 1960s moved on, Matala changed. It became a popular place for tourists, but its story is still very much tied to that special time. The wild, free spirit of those who lived in the caves has mostly faded, replaced by a more organized and business-like feel. Even so, the memory of its “hippie paradise” days still calls to people. You can see this history all around the village: in shops with a retro theme, in little gift stores, and most clearly in the bright street art and murals. These paintings show peace signs, famous musicians from that time, and hopeful sayings like “Today is Life, Tomorrow Never Comes,” gently keeping the stories of that bohemian past alive for all to see.

The Matala Beach Festival: A Modern Echo

A big part of how Matala remembers this past is the yearly Matala Beach Festival, which started in 2011. It was created to honor the hippies and try to bring back some of that old feeling. The festival mixes music, art, and culture, celebrating ideas like freedom and being creative. Thousands of people come, and it’s free to get in – a nice touch that reminds us of how things were back then, less about money. But the festival today is a big, planned event, run by local officials, and it helps the town’s businesses a lot. This is quite different from the spontaneous, anti-establishment days of the 1960s. It makes one pause and wonder: while we enjoy this echo of the past, are we truly connecting with the real, sometimes messy, story, or are we seeing a simpler, perhaps more comfortable, version of it?

Finding the Heart of Matala’s Story

In the end, the Matala we see now is very different from the freewheeling, simple commune of the 1960s. That direct link, the way people lived and the way society was, has truly been changed by time. But this doesn’t mean that its unique past isn’t deeply important. The real challenge for Matala today is to see how much it has changed, while still holding onto and respecting its counter-cultural story with an open heart. This means doing more than just painting colorful pictures or selling souvenirs. It’s about weaving that history into the life of the community today in a real way, making sure that the memory honors not just the hippies who came and went, but also the lasting values and traditions of the Cretan people who call Matala home. Looking after the local character, encouraging tourism that is kind to the place and its people, and making sure everyone feels involved – these are the things that matter. The vibrant, untamed spirit of the 1960s can’t be perfectly copied, but by remembering and thoughtfully including this special time in its ongoing story, Matala can be a place that truly respects all parts of its rich history while building a warm, welcoming, and locally rooted future for everyone.