Nikolaos Platon

Biography of Nikolaos Platon

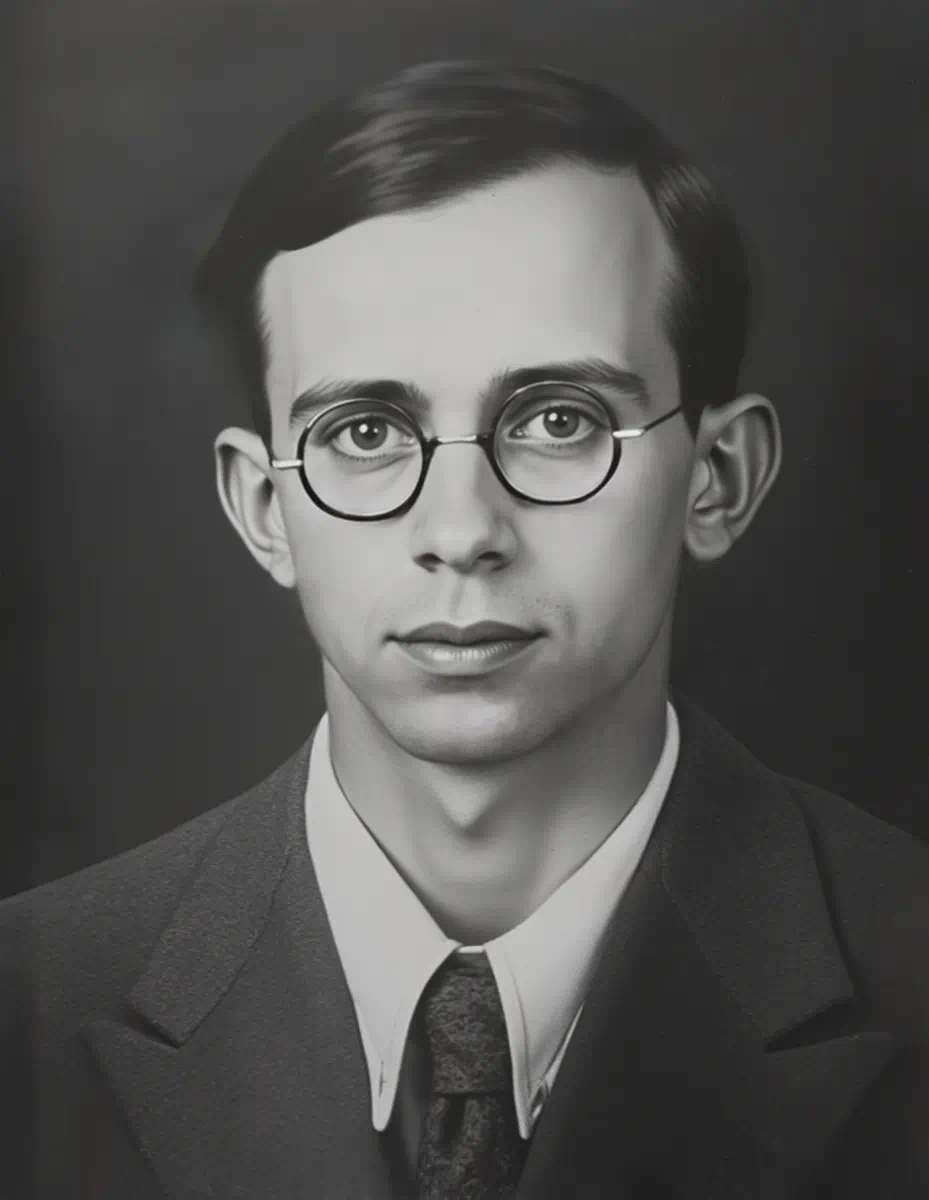

Nikolaos Platon (1909–1992) stands as one of the most influential Greek archaeologists of the 20th century, whose lifelong dedication profoundly shaped the modern understanding of the Minoan civilization of Bronze Age Crete. Born on January 8, 1909, in Kefalonia, and passing away in Athens on March 28, 1992, Platon’s career spanned a critical period of development in Aegean archaeology. His impact stemmed from a dual capacity: as a meticulous field excavator who brought to light one of Crete’s great Minoan palaces, and as a thoughtful theorist who challenged and refined the chronological framework for interpreting Minoan history.

His most celebrated achievement remains the discovery and subsequent decades-long excavation of the Minoan palace complex at Kato Zakros in eastern Crete, beginning in the early 1960s. Unlike the other major Minoan palatial centres, Zakros was found remarkably unlooted, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the final moments of Neopalatial Crete around 1450 BCE. Beyond this monumental fieldwork, Platon made a significant theoretical contribution by proposing an alternative system for Minoan chronology, structuring the island’s Bronze Age history around the construction, destruction, and rebuilding phases of its major palaces – the Prepalatial, Protopalatial, Neopalatial, and Postpalatial periods. This framework, while complementing the dominant pottery-based system established by Sir Arthur Evans, offered a new lens focused on major architectural and societal shifts.

Platon’s career serves as a crucial bridge in the history of Cretan archaeology. He entered the field when the “pioneer era” of figures like Evans was still dominant, yet his own major work, particularly at Zakros, was conducted with more modern methodologies. His contributions extended beyond excavation and theory; he played a vital role in safeguarding Crete’s heritage during World War II as Director of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum and held numerous influential positions within the Greek Archaeological Service throughout his long and distinguished career.

Formative Years and Early Career (1909 – c. 1940)

Nikolaos Eleftheriou Platon was born on the Ionian island of Kefalonia on January 8, 1909. His family relocated to Heraklion, Crete, during his youth, a move that proved formative for his future career. His father, Eleftherios Platon, served as the director of the state Chemical Laboratory in Heraklion. It was in Heraklion that Nikolaos completed his primary and secondary education, distinguishing himself as a diligent and disciplined student, graduating high school with the gold medal for excellence. His early exposure to the rich archaeological landscape of Crete undoubtedly fueled his academic interests.

He pursued higher education at the University of Athens, studying Literature and Archaeology within the Philosophical School. Seeking further specialization, he undertook doctoral studies in Paris at the prestigious École pratique des hautes études. This combination of a strong foundation in Greek academia and advanced training abroad provided him with a comprehensive perspective that would inform his later work. His early career path suggests a deliberate strategy to build a well-rounded expertise, grounding deep local knowledge of Crete within broader European academic standards, a contrast to some earlier excavators whose focus might have been more narrowly site-specific.

Platon embarked on his professional archaeological journey in 1930, securing a position as an assistant at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. Here, he worked under the guidance of Spyridon Marinatos, another towering figure in Aegean archaeology, who was then Ephor (Curator) of Antiquities. This early association placed Platon within the orbit of influential archaeological practice and debate from the outset. While sources differ on the exact timing of an early mainland appointment, one account places him as Ephor of Antiquities in Thebes (Boeotia) around 1935, before his more definitive return to Crete in a leadership role. This potential early experience outside Crete would have further broadened his understanding of Greek prehistory, encompassing the Mycenaean world alongside the Minoan.

During the 1930s, Platon gained crucial fieldwork experience in Crete. His most notable early project was assisting Spyridon Marinatos in the 1934–1935 excavations of the Arkalochori Cave in central Crete. This site yielded one of the richest Minoan metal hoards ever discovered, comprising a remarkable collection of bronze swords and daggers, copper ingots, and numerous double axes made of bronze, silver, and gold, including a unique axe inscribed with Cretan Hieroglyphic signs. These finds were interpreted as votive offerings deposited in a sacred cave, possibly dedicated to a war deity. Platon’s role as ‘epimelitis’ (assistant or supervisor) alongside Marinatos provided invaluable training in excavation techniques and the interpretation of complex ritual deposits. This collaboration likely shaped his early methodological approaches, though his later development of a distinct chronological system indicates an independent intellectual trajectory.

Evidence for Platon’s specific involvement in excavations at Poros-Katsampas, the harbour town of Knossos, before the 1940s is less direct in the available documentation. However, his later work involving Knossian material and his authority in inviting the British School to investigate nearby tombs in 1960 demonstrate his deep familiarity with the Knossos area developed over his career. His early fieldwork, particularly at Arkalochori, contributed significantly to the understanding of Minoan metallurgy, trade connections (implied by the metals), and religious practices during the period preceding the major palace excavations that would later define his career.

Wartime Service and the Heraklion Museum (c. 1939 – 1952)

The outbreak of World War II presented unprecedented challenges for the preservation of Greece’s archaeological heritage. Nikolaos Platon, appointed Director of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum and Ephor of Antiquities of Eastern Crete in 1939, found himself at the forefront of efforts to protect the invaluable Minoan collections under his care. His actions during this period demonstrated remarkable courage, dedication, and strategic thinking.

In 1941, while serving as a soldier on the Albanian front following Italy’s invasion of Greece, Platon received news of the German invasion and the subsequent Battle of Crete (May 1941). Deeply concerned for the safety of the museum’s artifacts, he made a determined effort to return to the occupied island. Displaying considerable resourcefulness, he reportedly utilized his connection with the German archaeologist Kurt Gebauer at the German Archaeological Institute in Athens to secure permission for a flight back to Crete, a perilous journey undertaken with the express purpose of safeguarding the island’s cultural treasures from anticipated Nazi looting and wartime destruction.

Upon his return, Platon orchestrated a comprehensive plan to hide the museum’s most significant objects. The newly constructed museum building fortunately possessed a spacious, reinforced concrete basement shelter. Although not impervious to heavy bombing, it offered the best available protection for delicate and irreplaceable antiquities that could not be buried outdoors. Due to space limitations, a rigorous selection process was necessary. Platon supervised the careful packing of these chosen artifacts; some were placed in specially constructed wooden crates, occasionally lined with tin for extra protection, while others, owing to wartime shortages, received more rudimentary packing. The shelter was filled densely, floor to ceiling. For larger, less fragile items, such as sculptures, trenches were dug within the museum grounds, and the objects were buried. These meticulous and brave efforts, undertaken amidst the dangers of occupation and Allied bombing raids (which did hit the museum building, though after German military material had reportedly been moved elsewhere), proved successful. Thanks to Platon’s exertions, the core collection of the Heraklion Museum survived the war intact. His ability to navigate the complexities of occupation, even leveraging connections with individuals on the opposing side for the sake of cultural preservation, highlights a strategic pragmatism that likely bolstered his reputation within the Greek Archaeological Service in the post-war era. His success in safeguarding Heraklion’s treasures stood as a testament to his commitment and competence.

Following the liberation, Platon faced the enormous task of overseeing the recovery and restoration of the museum’s collections. He supervised the painstaking process of locating, unpacking, conserving, and re-exhibiting the thousands of artifacts that had been hidden. This intensive period of re-engagement with the entirety of the museum’s holdings, encompassing material from Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and numerous other Minoan sites, provided Platon with an unparalleled synoptic overview of Minoan material culture across different regions and time periods. This deep immersion, lasting until the museum finally reopened its doors to the public in 1952, likely served as crucial intellectual groundwork for his later formulation of the palace-based chronological system. It allowed him to perceive overarching patterns in architectural development and destruction sequences across the island, moving beyond the site-specific focus of earlier excavators and laying the foundation for a more integrated historical framework.

Post-War Leadership and the Path to Zakros (1945 – 1961)

In the aftermath of World War II, Nikolaos Platon emerged as a central figure in Cretan archaeology. In 1945, his responsibilities were expanded, and he was appointed Ephor of Antiquities for the entirety of Crete, a position of significant authority that he held until 1962. This island-wide oversight represented a consolidation of archaeological administration compared to earlier divisions, enabling Platon to direct resources, grant permits for excavations, and pursue a more unified approach to the study and preservation of Crete’s past. This centralized role undoubtedly facilitated the planning and execution of major archaeological initiatives in the subsequent decades.

He continued to serve as Director of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum through the initial post-war years, overseeing its reopening in 1952 and its operations until Stylianos Alexiou eventually took over the directorship following the addition of a new wing in 1964.

Platon remained active in fieldwork and restoration projects during this period. He directed restoration efforts at the Minoan palace of Malia between 1954 and 1962. Significantly, during conservation and restoration work within the Palace of Knossos between 1955 and 1957, he conducted targeted test excavations. These soundings yielded important, well-stratified early Prepalatial pottery (dating to Early Minoan I – Early Minoan IIB) and a rare clay sealing from an EM IIB context. This material provided valuable new evidence regarding the extent, scale, and external contacts (including the Cyclades and other parts of Crete) of the settlement at Knossos during its earliest phases. This work demonstrates Platon’s continued engagement with Crete’s primary Minoan site, integrating research objectives with necessary conservation activities and employing targeted excavation to answer specific questions about the site’s history—a methodologically nuanced approach. It highlights his respect for Knossos’s importance while simultaneously gathering data that would inform his broader, multi-site chronological framework.

His authority as Ephor is further evidenced by his invitation to the British School at Athens, represented by Sinclair Hood, to investigate a group of Middle and Late Minoan tombs (site KSP/60) that had been accidentally exposed near Knossos in 1960. He also undertook initial excavations at the remote site of Lissos in southwestern Crete between 1957 and 1961, focusing primarily on the sanctuary of Asclepius, and conducted significant work at Onythe Gouledianon in Rethymno in the mid-1950s.

It was during this period of post-war leadership and renewed archaeological activity that Platon formally proposed his influential revision of Minoan chronology. Building on the insights likely gained during the intensive re-examination of the Heraklion Museum collections and his ongoing fieldwork, he presented his system based on palatial phases in 1958 (some sources cite 1961), offering a new framework for understanding the broad sweep of Minoan history. This theoretical work, combined with his extensive practical experience and administrative authority, set the stage for his most famous undertaking: the excavation of Zakros.

Other Cretan Sites

While Nikolaos Platon is most renowned for his decades-long excavation of the palace at Kato Zakros, his archaeological activities in Crete extended to other significant, albeit less monumental, sites. These explorations demonstrate his broad engagement with the island’s past, spanning different periods and site types, reflecting the wide scope of his responsibilities as Ephor of Antiquities.

Arkalochori Cave: As mentioned earlier, one of Platon’s formative fieldwork experiences was assisting Spyridon Marinatos in the 1934-1935 excavations of the Arkalochori Cave. This sacred cave yielded an exceptional hoard of Minoan metalwork, including bronze weapons and votive double axes, providing crucial insights into Minoan religion and metallurgy. Platon’s role here, early in his career, exposed him to the richness of non-palatial Minoan contexts.

Onythe Gouledianon (Rethymno): In the mid-1950s (specifically continuing work in 1955), Platon excavated at Onythe, the site of an ancient city possibly identifiable as Phalanna. This work was prompted by the discovery of impressive Archaic relief pithoi (large storage jars) decorated with animals and mythical creatures, dating to the late 7th century BCE. His excavations uncovered substantial Archaic houses (designated House A and House B). House A, measuring 21×36 meters, was extensively investigated, revealing multiple rooms, including storerooms filled with pithoi and smaller vessels, a room yielding the relief pithoi fragments, and another containing a marble basin with a lion-head spout. House B appeared even larger but was not fully excavated at the time. The finds confirmed a relatively short occupation period for House A in the late 7th and early 6th centuries BCE. Platon noted these were among the largest Archaic Greek houses excavated in Crete up to that point. In the same vicinity (Kera Onythe), Platon also excavated a significant Paleochristian basilica, dating probably to the late 5th or late 6th century CE. This basilica featured elaborate geometric mosaic floors, distinct pastophoria (side chambers near the altar), and a synthronon (bench for clergy) in the apse.

Lissos: Between 1957 and 1961, Platon conducted the first systematic excavations at the remote ancient site of Lissos in southwestern Crete. Lissos was known in antiquity as an important healing center. Platon’s work focused primarily on uncovering the Sanctuary of Asclepius, the Greek god of healing. His excavations revealed the temple structure, which had been destroyed by an earthquake, sealing a significant collection of Hellenistic sculptures (including statues of Asclepius and Hygieia), votive offerings, and inscriptions. These finds attested to the sanctuary’s importance and prosperity. Platon’s work also identified other features of the town, including Roman baths and a Greco-Roman necropolis. Recent excavations (starting 2022) have focused on uncovering a small Roman-era theater/odeon near the sanctuary, building directly on Platon’s pioneering investigations.

These examples illustrate that Platon’s archaeological interests and responsibilities in Crete were not confined solely to the great Minoan palaces. His work encompassed sacred caves, Archaic cities, later Classical and Roman sanctuaries, and early Christian basilicas, contributing to a more rounded picture of Crete’s long and complex history across various regions and time periods.

The Discovery and Excavation of Zakros (1961 onwards)

The culmination of Nikolaos Platon’s long engagement with Cretan archaeology arrived with the excavation of the Minoan palace at Kato Zakros. Situated in a sheltered bay on the far eastern coast of Crete, south of Palaikastro, Zakros occupied a strategic position often described as the Minoan “Gateway to the East”. While the site’s potential had been recognized since the 19th century by travellers and early researchers like T.A.B. Spratt, F. Halbherr, and L. Mariani, and preliminary excavations of surrounding houses were undertaken by David G. Hogarth of the British School at Athens in 1901, the palace itself remained undiscovered.

In 1961 or 1962, Nikolaos Platon, then Ephor of Cretan Antiquities, initiated new excavations at Kato Zakros. His work quickly led to the uncovering of the fourth major Minoan palace found on Crete, launching an extensive research project that would continue under his direction for decades, with annual reports appearing regularly in the Praktika tes Archaiologikes Etaireias. The excavation is widely regarded as one of the most significant Minoan archaeological projects undertaken since World War II.

Two factors made the Zakros excavation exceptionally important. Firstly, unlike Knossos, Phaistos, and Malia, the palace at Zakros was found largely unlooted. Its destruction, dated to the Late Minoan IB period (around 1450 BCE) and likely caused by a sudden, catastrophic event—possibly earthquake and fire linked to the eruption of the Thera volcano—effectively sealed the site, preserving its contents in situ. This provided archaeologists with a unique “time capsule” of Neopalatial life. Secondly, the excavation benefited from the advancements in archaeological methodology that had occurred since the pioneering work at the other palaces some 60 years earlier. Platon and his team were able to employ more modern and scientific techniques in excavation and recording. This combination of exceptional preservation and improved methodology allowed Zakros to provide a crucial comparative dataset, offering a clearer, less disturbed picture of a Minoan palace at the height of its development than was possible at the earlier, sometimes heavily reconstructed sites like Knossos. The clear stratigraphy and undisturbed finds at Zakros provided unambiguous evidence for the state of a major centre at a specific destruction horizon, directly relevant to the Neopalatial/Postpalatial transition in Platon’s own chronological scheme.

The palace itself, though smaller than Knossos, was a substantial complex covering over 8,000 square meters and containing an estimated 300 rooms and spaces across multiple levels. It featured the characteristic elements of Minoan palatial architecture: a large Central Court (approximately 30 x 12 meters), around which were arranged distinct wings with specialized functions. The West Wing housed the main shrine areas, storerooms, and administrative archives; the East Wing contained royal apartments and further administrative spaces; the South Wing included a complex of workshops; and the North Wing featured storage areas and a lustral basin. Evidence of sophisticated features like drainage systems, light wells, and elaborate decoration including frescoes was also uncovered.

The unplundered nature of the site yielded an extraordinary wealth of artifacts. Among the most significant discoveries were:

- The Linear A Archive: Located in an archive room (XVI) in the West Wing, Platon unearthed clay tablets inscribed in the still-undeciphered Linear A script, stored in wooden boxes on shelves. These provide invaluable, albeit enigmatic, evidence for Minoan administration, economy, and language.

- The Treasury: A room designated as the “Treasury of the Shrine” (XXV) contained a spectacular collection of ritual vessels (rhyta, chalices, ewers) crafted from luxurious and often imported materials. Masterpieces included the famous chlorite Bull’s Head rhyton, a serpentine rhyton depicting a peak sanctuary, and an exquisite rhyton carved from rock crystal with a beaded handle and gold-leaf decoration. Other vessels were made of Egyptian alabaster, faience, obsidian, basalt, and limestone. Numerous bronze double axes were also found here.

- Evidence of Trade: Discoveries such as elephant tusks, copper oxhide ingots (raw copper likely from Cyprus), and Canaanite storage jars confirmed Zakros’s role as a major hub for international trade, particularly with the Near East, Egypt, and potentially Africa.

- Workshops: The South Wing revealed evidence of specialized craft production, including workshops for faience, stone vase making, and possibly perfumery. Loom weights indicated textile production, and a large furnace near the harbour road suggested metalworking capabilities.

- Burials: Numerous Minoan tombs, primarily cave burials, were excavated in the dramatic gorge leading to the site, aptly named the “Gorge of the Dead” by Platon himself after these discoveries.

The discoveries at Zakros fundamentally altered the understanding of Minoan Crete. They confirmed the existence of a powerful administrative and economic centre in the far east of the island, strategically positioned to control maritime trade routes. The sheer quality and quantity of the finds, often described as “royal” and superior in craftsmanship to those from other palaces, highlighted the wealth and sophistication of this eastern outpost. This concentration of luxury goods, imported materials, and evidence for specialized production, despite the palace’s relatively modest size compared to Knossos, strongly suggests a specialized function focused on international exchange, perhaps playing a role disproportionate to its physical scale within the broader Minoan political and economic landscape. Furthermore, the close physical proximity of the administrative archive, the religious treasury, and the workshops within the palace complex underscores the deeply integrated nature of political authority, economic production, and religious ideology in the Minoan palatial system, challenging models that might attempt to rigidly separate these spheres of activity.

Platon’s Chronological Framework

Beyond his contributions as an excavator, Nikolaos Platon made a lasting impact on Minoan studies through his proposal of an alternative chronological system. Introduced formally around 1958 or 1961, this framework offered a different way to structure Minoan history compared to the long-established system developed by Sir Arthur Evans based primarily on pottery styles.

Platon’s system is rooted in the major architectural phases and historical events observed in the stratigraphy of the principal Minoan palaces: Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and, later incorporated, his own site of Kato Zakros. It divides the Minoan Bronze Age into four main periods based on the life cycles of these central complexes:

- Prepalatial Period: The era before the construction of the first palaces, corresponding roughly to Evans’s Early Minoan (EM) I, EM II, EM III, and Middle Minoan (MM) IA phases (c. 3100–1925 BCE).

- Protopalatial Period (Old Palace Period): From the initial construction of the first palaces to their widespread destruction, aligning with MM IB and MM II (c. 1925–1700 BCE).

- Neopalatial Period (New Palace Period): The era of the rebuilt, often more elaborate palaces, considered the zenith of Minoan civilization, ending with another wave of destructions. This corresponds to MM III, Late Minoan (LM) IA, and LM IB (c. 1700–1450 BCE).

- Postpalatial Period: The period following the final destruction or abandonment of most palace centres (except perhaps for a final phase at Knossos), during which Minoan culture continued, often under Mycenaean influence. This covers LM II, LM IIIA, LM IIIB, and LM IIIC (c. 1450–1075 BCE). Some scholars insert a “Final Palatial” or “Monopalatial” period for LM II Knossos.

The rationale behind Platon’s system was to provide a chronological framework grounded in major, observable historical events—the building, destruction, and rebuilding of the palaces—which presumably reflected significant societal shifts, political changes, or widespread natural disasters. This contrasted with Evans’s system, which relied on the evolution of pottery styles. While pottery is ubiquitous and allows for fine dating, its stylistic changes might not always perfectly align with major historical turning points and could be subject to regional variations or time lags in adoption. Furthermore, Evans’s system was developed primarily at Knossos and was sometimes seen as an awkward fit for the sequences at other sites. Platon aimed for a structure based on events with potentially island-wide significance, reflected directly in the architectural stratigraphy of multiple key centres.

Platon’s palatial chronology was widely accepted by the scholarly community, not as a replacement for Evans’s system, but as a valuable complementary framework. The two systems are largely commensurate, meaning their period boundaries align reasonably well, and they are often used side-by-side in archaeological literature. Platon’s system offers a lens that emphasizes architectural development, socio-political organization, and major historical events, while Evans’s system provides finer chronological resolution based on the ubiquitous and well-studied ceramic evidence.

The following table illustrates the correlation between the two systems and key characteristics of each period:

Table 1: Comparative Minoan Chronological Frameworks

Approximate Dates (BCE) | Platon’s Palatial Period | Evans’s Ceramic Period | Key Characteristics / Events |

c. 3100–2650 | Prepalatial | EM I | Introduction of copper; painted pottery; growth of settlements. |

c. 2650–2200 | Prepalatial | EM II | Increased trade (Egypt, Syria); seals adopted; monumental buildings appear at future palace sites; Vasiliki ware. |

c. 2200–1925 | Prepalatial | EM III / MM IA | Population growth at major sites (Knossos, Phaistos, Malia); major construction projects; polychrome handmade pottery (MM IA start). |

c. 1925–1875 | Protopalatial | MM IB | First palaces constructed; potter’s wheel adopted; Kamares ware appears. |

c. 1875–1700 | Protopalatial | MM II | Development of writing systems (Cretan Hieroglyphic, Linear A); height of Kamares ware; ends with widespread destruction (earthquakes?). |

c. 1700–1625 | Neopalatial | MM III / LM IA | Palaces rebuilt, often larger/more complex; flourishing of frescoes, arts; Linear A script common; Thera eruption occurs near end of LM IA (c. 1600 BCE). |

c. 1625–1450 | Neopalatial | LM IB | Height of Minoan civilization; Marine Style pottery; extensive trade networks; ends with widespread destruction of most sites except Knossos. |

c. 1450–1420 | Postpalatial (Final Pal.) | LM II | Knossos remains occupied, likely under Mycenaean control; Linear B script appears at Knossos. |

c. 1420–1330 | Postpalatial | LM IIIA | Mycenaean influence widespread; Knossos destroyed (c. 1370 BCE?); rebuilding at some sites (e.g., Chania). |

c. 1330–1200 | Postpalatial | LM IIIB | Continued Mycenaean-style culture; decline in complexity at some sites. |

c. 1200–1075 | Postpalatial | LM IIIC | “Post-palatial” decline; refuge settlements; transition towards Iron Age. |

(Note: Dates are approximate and subject to ongoing refinement based on scientific dating methods like radiocarbon analysis and synchronisms with Egypt and the Near East)

By focusing on the shared histories of the major palatial centres, Platon’s system implicitly highlights the interconnectedness of Minoan Crete, suggesting that major events often had island-wide repercussions. This perspective aligns with archaeological evidence for phenomena like the widespread LM IB destructions. Furthermore, the development of this architecture- and event-based chronology reflects a broader shift in mid-20th-century archaeological thought, moving towards integrating stratigraphic and architectural evidence more centrally into historical interpretation, complementing the earlier primary reliance on artifact typology.

Later Career and Broader Contributions (1960s – 1992)

While the excavation of Zakros occupied much of Nikolaos Platon’s attention from the 1960s onwards, his career continued to be multifaceted, encompassing significant academic roles and responsibilities outside of Crete.

In 1965, he was appointed Professor of Prehistoric Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, bringing his extensive knowledge of the Aegean Bronze Age to a major academic institution. Later, in 1974, he became a professor at the newly established University of Rethymno on Crete, contributing to the development of archaeological studies within his adopted homeland.

His expertise was also called upon for high-profile positions on the Greek mainland. From 1960 to 1962, he served as the Director of the Archaeological Region of Athens and Director of the Acropolis Museum (then situated on the Acropolis itself). During this tenure, he grappled with the complex challenges of preserving the Acropolis monuments, addressing the detrimental effects of earlier restoration attempts (notably the use of rusting iron clamps) and the growing impact of atmospheric pollution. He initiated crucial conservation work, including on the Karyatids of the Erechtheion porch, and oversaw the creation of an exhaustive photographic and descriptive archive of the Acropolis monuments, a vital resource for future preservation efforts. His work during this period foreshadowed the major conservation concerns that would lead to the large-scale Acropolis Restoration Project decades later. In 1965, while still engaged with Acropolis matters, he conducted excavations on the South Slope, behind the Stoa of Eumenes, uncovering a Mycenaean chamber tomb, adding to the understanding of the site’s deep prehistoric roots.

Following his Athens directorship, in 1962, Platon was appointed head of the archaeological region of Boeotia, where he undertook excavations at the important Mycenaean centre of Thebes. This ability to operate at the highest levels of archaeological administration and research in both Minoan Crete and Classical/Mycenaean mainland Greece demonstrates a remarkable breadth of expertise and high standing within the entire Greek archaeological establishment, a versatility not common among specialists focused solely on one region or period.

Throughout his later career, Platon continued to publish extensively. His detailed annual excavation reports from Zakros appeared for many years in the Praktika tes Archaiologikes Etaireias (Proceedings of the Archaeological Society at Athens). He also authored numerous scholarly articles and several books, including major works synthesizing his findings at Zakros and his understanding of Minoan civilization.

Nikolaos Platon passed away in Athens on March 28, 1992, at the age of 83, leaving behind a rich legacy of discovery and scholarship.

Legacy and Family

Nikolaos Platon’s legacy is firmly secured by his monumental contributions to Minoan archaeology, particularly the excavation of Zakros and the development of the palatial chronological system. He is widely recognized as a leading figure in 20th-century Greek archaeology. The discovery of the unlooted palace at Zakros provided an unprecedented window into Neopalatial society, revealing crucial evidence about administration, religion, trade, and daily life. His chronological framework offered a vital alternative and complementary perspective for interpreting the trajectory of Minoan civilization, shifting focus towards major historical events reflected in architecture. His courageous and effective actions during World War II ensured the preservation of irreplaceable cultural heritage. Furthermore, the application of more rigorous, modern excavation methods at Zakros marked a methodological advance compared to some earlier work in Crete.

Platon’s work effectively bridged the “pioneer era” of Cretan archaeology with later developments. While building on the foundations laid by figures like Evans and Hogarth, he moved beyond them through enhanced methodological rigor at Zakros and by proposing a theoretical framework that challenged the absolute primacy of the Knossos-centric, pottery-based chronology. His career demonstrated attention to stratigraphy, context, the potential of diverse site types (like Lissos and Onythe), and the integration of conservation with research. For his contributions, he received numerous accolades, including honours from the Academy of Athens, other academic institutions in Greece and abroad, the Italian state, and the Greek state (Order of the Phoenix).

The continuation of Platon’s work is also part of his legacy, notably through his family. His son, Lefteris (Eleftherios) Platon, followed in his father’s footsteps and is himself a prominent archaeologist specializing in the Aegean Bronze Age. Currently an Associate Professor at the University of Athens, Lefteris Platon directs the Zakros Project, which is dedicated to the ongoing study and final scientific publication of the vast amounts of material recovered during his father’s decades-long excavations. This familial continuity provides a direct mechanism for ensuring that Nikolaos Platon’s most significant fieldwork achieves full scholarly dissemination, addressing the common challenge of publishing large-scale, long-term archaeological projects. Lefteris Platon has published widely on Minoan subjects, including Zakros, Minoan presence on other islands like Karpathos, and aspects of Minoan religion and society.

While the initial query prompting this report mentioned the possibility of two of Nikolaos Platon’s children pursuing archaeology, the available documentation robustly confirms only Lefteris Platon in this role. One source mentions a Maria Platonos directing an excavation, but provides no information linking her to Nikolaos Platon. Therefore, based on the provided evidence, confirmation extends only to his son, Lefteris. This highlights the importance of verifying biographical details against reliable sources, as narratives surrounding well-known figures can sometimes incorporate unconfirmed information.

Nikolaos Platon’s Enduring Contributions to Aegean Archaeology

Nikolaos Platon’s career represents a paradigm of archaeological dedication, spanning fieldwork, theoretical innovation, museum curation, heritage protection, and academic teaching. From his early work assisting Marinatos at Arkalochori, through his excavations at Archaic Onythe and Hellenistic/Roman Lissos, to his decades-long directorship of the Zakros project, he consistently demonstrated meticulousness and a deep commitment to understanding Crete’s past across different eras. His wartime efforts to safeguard the Heraklion Museum’s treasures stand as a profound act of cultural stewardship.

His two most enduring contributions are undoubtedly the excavation of the unlooted Neopalatial palace of Zakros and the formulation of the palatial chronological system. Zakros provided an unparalleled, undisturbed view of Minoan palatial society at its height, revealing insights into its eastern trade connections, administrative complexity, religious practices, and artistic achievements. The palatial chronology, based on the life cycles of Crete’s major centres, offered a crucial framework for interpreting Minoan history through the lens of major architectural and societal events, complementing the established pottery-based system and stimulating new perspectives on the island’s development.

Nikolaos Platon can be seen as a pivotal transitional figure in Aegean archaeology. He mastered the knowledge accumulated by the pioneers who preceded him but significantly advanced the discipline through the application of more systematic methodologies, the development of broader theoretical frameworks that integrated evidence from multiple sites, and a lifelong dedication to the preservation, interpretation, and dissemination of Greece’s rich archaeological past. His legacy continues not only through the vast body of knowledge he generated but also through the ongoing research and publication efforts focused on his discoveries, ensuring his work remains central to the study of Minoan civilization and the broader history of Crete.