Arthur Evans

Biography of Arthur Evans

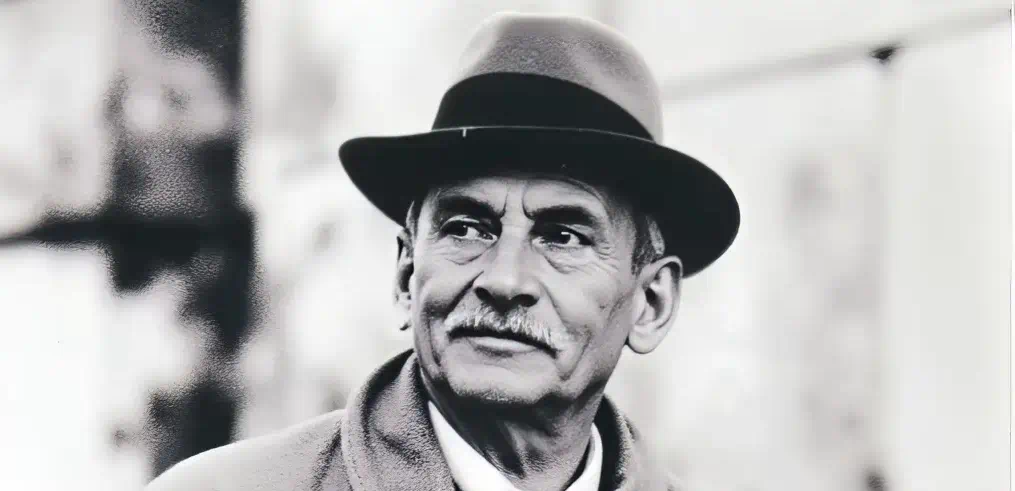

Sir Arthur John Evans (1851–1941) was a prominent British archaeologist best known for his extensive excavations at Knossos on the island of Crete. Starting around 1900, his work uncovered the remains of a significant Bronze Age civilization, which he named “Minoan” after the mythical King Minos. This term and the concept of Minoan civilization fundamentally shaped the 20th-century understanding of European prehistory, revealing a complex society predating Classical Greece with distinct art, architecture, and writing systems.

Evans’s legacy is complex. His archaeological discoveries laid the foundation for studying Bronze Age Crete, but his interpretations and physical reconstructions at Knossos have generated significant controversy. He did not simply find the ruins; he actively constructed a narrative for the civilization, linking it directly to Greek mythology through the name “Minoan.” This interpretive approach, evident from the beginning, highlights his role in shaping the perception of the culture he brought to light.

Formative Years: Family, Education, and Early Pursuits (1851-1884)

Arthur John Evans was born on July 8, 1851, in Nash Mills, Hertfordshire, England. His father, Sir John Evans, was both a successful paper manufacturer and a respected antiquarian, numismatist, geologist, and archaeologist. This background provided Arthur with financial security and early exposure to archaeology, collecting, and intellectual circles. His mother, Harriet Ann Dickinson, died when he was seven. He was educated at Harrow School (1865-1870) and Brasenose College, Oxford, graduating in 1874 with first-class honours in Modern History.

Even during his studies, Evans favored archaeological exploration and travel. He visited sites in Austria and France and journeyed through the Carpathians, Lapland, Finland, and Sweden, documenting observations and artifacts. A short period at the University of Göttingen proved unsatisfactory, and he returned to the Balkans.

His early career involved significant engagement with Balkan politics. He traveled through Bosnia and Herzegovina during periods of insurrection against Ottoman rule (1871, 1875), sympathizing with the South Slavs. His book, Through Bosnia and the Herzegovina on Foot (1876), established him as a regional expert. In 1877, he became the Balkan correspondent for the Manchester Guardian, based in Ragusa (Dubrovnik). His critical reporting led to his arrest by Austrian authorities in 1882 and expulsion from the region. In 1878, he married Margaret Freeman, daughter of historian Edward Augustus Freeman; she died in 1893. During this period, he continued his antiquarian pursuits, locating Roman sites, conducting small excavations, and collecting coins and gems. His near-sightedness reportedly aided his examination of small details.

These early years show Evans’s preference for fieldwork over formal academia, his strong political convictions intertwined with scholarly interests, and his independent nature. This approach foreshadowed his later work in Crete.

The Ashmolean Keepership and the Path to Crete (1884-1900)

In 1884, Evans was appointed Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford, a position he held until 1908. He significantly transformed the museum, expanding its archaeological collections, securing donations, and overseeing its move to a larger building in 1894. Later, he facilitated the transfer of the Bodleian Library’s coin collection to the Ashmolean.

Around 1893-1894, Evans’s focus shifted to Crete, sparked by his interest in small engraved seal stones from the island bearing symbols he believed represented a pre-alphabetic script. He hypothesized these were evidence of a lost Aegean civilization predating the Mycenaeans. His ideas were published in Cretan Pictographs and Prae-Phoenician Script (1895).

He first visited Crete in 1894, traveling extensively over the next few years to collect seal stones and other evidence. During his 1894 trip, he visited the Kephala hill near Heraklion, the site of Knossos. He observed ruins and met Minos Kalokairinos, who had conducted trial digs there in 1878. Convinced of the site’s importance, Evans decided to excavate it himself.

Acquiring excavation rights was difficult under Ottoman rule. Heinrich Schliemann had previously failed to buy the site. Evans, however, was persistent. He built local contacts and anticipated political changes. Following the establishment of the autonomous Cretan State in 1898, the process became easier. Evans had already begun purchasing parts of the Kephala hill. In 1899, he established the Cretan Exploration Fund, largely financed by his family wealth, possibly as a way to navigate ownership rules. By early 1900, he had purchased the entire Knossos site and secured the excavation permit. His position at the Ashmolean provided institutional credibility, relevant experience in managing large projects, and a base for his research and collections.

Excavating Knossos: Unearthing a Civilization (1900-1931)

Evans began excavating Knossos on March 23, 1900. The initial years (1900-1905) saw rapid progress, uncovering most of the palace complex. Work continued intermittently under his direction until 1931. The excavation employed a large local workforce.

Duncan Mackenzie served as Evans’s field director during the crucial early seasons. Mackenzie managed the daily operations and maintained detailed excavation records (‘Daybooks’), which provided essential stratigraphic and contextual data for Evans’s interpretations and publications, including The Palace of Minos. Mackenzie made key contributions to understanding Minoan pottery sequences and site chronology. Although Evans held ultimate authority, Mackenzie provided methodological rigor.

The excavation methods involved stratigraphic analysis, which was advanced for the time, focusing on pottery sequences for relative chronology. However, large-scale clearances aimed at revealing architecture sometimes compromised the detailed recording of find contexts by modern standards. The project was primarily funded by Evans’s personal and family wealth, channeled partly through the Cretan Exploration Fund.

Discoveries at Knossos included:

- The Palace Complex: A large, multi-story structure around a Central Court, its complex plan associated by Evans with the Labyrinth myth. It featured advanced architecture like ashlar masonry, timber framing, distinctive columns, and water management systems.

- The Throne Room: Found in 1900, featuring a gypsum throne, benches, griffin frescoes, and a sunken basin. Evans interpreted it as King Minos’s seat.

- Frescoes: Numerous wall paintings depicting scenes like bull-leaping, processions, nature motifs (dolphins, monkeys, plants), and the composite “Priest-King” figure. These were conserved and often extensively restored by artists like Émile Gilliéron père et fils.

- Snake Goddess Figurines: Faience figures found in 1903 in the “Temple Repositories,” depicting females with snakes. Significantly restored, Evans interpreted them as a Mother Goddess and priestess.

- Linear A and Linear B Tablets: Thousands of clay tablets inscribed with two unknown scripts. Evans recognized them as distinct writing systems used for administration. Linear B was later deciphered as early Greek.

- Other Artifacts: Large quantities of pottery (e.g., Kamares ware, Marine Style), stone vases, seals, storage jars (pithoi), and evidence of metalworking.

Table 1: Key Discoveries by Arthur Evans at Knossos (c. 1900-1931)

Discovery/Feature | Approx. Date | Significance / Initial Interpretation by Evans |

Throne Room | 1900 | Interpreted as King Minos’s seat; ceremonial/political center. Gypsum throne, griffin frescoes. |

Linear B Tablets | 1900 onwards | Thousands found; recognized as administrative script; Evans believed it recorded the Minoan language. |

Palace Complex Layout | 1900-1905 | Vast, multi-storied; seen as evidence for Labyrinth myth; indicated complex, centralized society. |

Bull-Leaping Fresco | c. 1900-1901 | Depicted figures vaulting over a bull; interpreted as ritual sport/ceremony. |

Snake Goddess Figurines | 1903 | Faience figures from “Temple Repositories”; interpreted as Great Mother Goddess and priestess. |

Grand Staircase | c. 1901-1904 | Impressive multi-storied staircase; showed sophisticated architecture; required major reconstruction. |

“Priest-King” Fresco | Early finds | Reconstructed figure interpreted as ruler/priest; now known to be a composite of unrelated fragments. |

Linear A Script | Found early | Recognized as an earlier, distinct script, also undeciphered by Evans. |

Defining “Minoan”: Chronology, Culture, and Interpretation

Evans coined the term “Minoan,” drawing on the myth of King Minos and the Labyrinth, to name the civilization discovered at Knossos and distinguish it from mainland Mycenaean culture. This name immediately framed the findings within mythology.

He established a chronological framework based mainly on pottery styles studied by Mackenzie: Early Minoan (EM), Middle Minoan (MM), and Late Minoan (LM), each subdivided (I, II, III). This system was correlated with Egyptian chronology using artifact cross-finds. While refined and debated, the EM-MM-LM structure remains fundamental to Minoan archaeology.

Evans characterized Minoan culture as highly artistic, naturalistic, and distinct from Mycenaean or Near Eastern traditions. He interpreted Minoan society as largely peaceful (a Pax Minoica), possibly maintained by a strong navy (thalassocracy). Based on female depictions, he speculated about prominent roles for women, potentially suggesting a matriarchal society. He envisioned rule by “Priest-Kings” combining secular and religious power.

In Evans’s view, Minoan religion centered on a “Great Mother Goddess,” represented by the Snake Goddess figurines and associated with symbols like the double axe (labrys) and horns of consecration. This interpretation aligned with contemporary anthropological theories (e.g., Frazer, Bachofen).

This vision of Minoans—peaceful, artistic, nature-focused, goddess-worshipping—was appealing but has been challenged. Evidence for pacifism is debated, matriarchy remains speculative, and the single Mother Goddess concept is questioned. Evans’s synthesis appears influenced by the archaeological data, contemporary intellectual trends, his own ideals, and perhaps personal factors.

Reconstruction, Controversy, and Legacy

Evans undertook extensive physical reconstruction at Knossos after 1905, aiming to preserve the site and make its multi-story structure understandable. He argued interventions were needed to protect fragile materials like mudbrick and frescoes and prevent structural collapse. Architects Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, and later Piet de Jong were involved.

Reinforced concrete, a new material at the time, was widely used to replace wooden elements (beams, columns), build upper levels, and consolidate walls. Steel joists were also used. This created a mix of ancient ruins and early 20th-century construction.

These reconstructions drew heavy criticism from archaeologists. Critics argued they were speculative, inaccurate, used irreversible modern materials that obscured original features, and reflected Evans’s personal vision more than Minoan reality. Some compared the aesthetic negatively to modern structures. Early conservation methods for artifacts have also been questioned.

Evans’s interpretations also sparked debate. His insistence on Minoan cultural dominance over the mainland was challenged by archaeologists Alan Wace and Carl Blegen. Based on mainland excavations, Wace and Blegen argued for greater Mycenaean autonomy and proposed later dates for key monuments, suggesting Mycenaeans eventually controlled Knossos. The dispute became heated, with accusations that Evans used his influence to hinder Wace’s career. The decipherment of Linear B as early Greek in 1952 by Michael Ventris largely supported Wace and Blegen’s view of Greek speakers controlling Knossos in its final phase.

Despite controversies, Evans’s influence remained significant. He was knighted in 1911. His multi-volume work, The Palace of Minos at Knossos (1921-1936), became the foundational text on his discoveries. He held positions as Honorary Keeper of the Ashmolean and Extraordinary Professor at Oxford. He died on July 11, 1941, shortly after his 90th birthday, dividing his later years between England and his Villa Ariadne near Knossos.

The Knossos reconstructions remain controversial but have contributed to the site’s preservation and popularity, making the Bronze Age palace accessible, albeit through the lens of its excavator’s vision.