The Hellenistic Crucible: Conflict, Piracy, and Intervention (c. 323-67 BCE)

The era following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE plunged the Greek world into a century and a half of large-scale warfare between his successor kingdoms. For Crete, this new geopolitical landscape amplified its existing tendencies toward conflict, transforming the island into a volatile arena of internal strife, foreign intervention, and rampant piracy.

The Collapse of the Old Order

The endemic warfare of the Classical period escalated dramatically in the Hellenistic age. The traditional aristocratic order in many cities began to collapse under the pressure of constant infighting, and the island’s economy was severely weakened by the destruction wrought by these prolonged wars. The Lyttian War of c. 220 BCE serves as a prime example of the era’s chaos. This was not a simple conflict between two cities but a complex island-wide struggle between two major coalitions—one led by Knossos and Gortyn, the other by Lyttos and Polyrrhenia. The war quickly drew in outside powers, including the Aetolian League and the Macedonian kingdom, demonstrating the complete fragmentation of the Cretan political scene and its vulnerability to foreign manipulation.

A Pawn in Great Power Politics

Crete’s strategic location, combined with its status as the preeminent recruiting ground for elite mercenary archers, made it an object of intense interest for the great Hellenistic powers. The Ptolemies of Egypt, the Antigonids of Macedon, and the formidable naval republic of Rhodes all vied for influence over the island. They interfered constantly in Cretan affairs, offering military and financial support to different factions, establishing garrisons in allied cities, and recruiting thousands of Cretan soldiers for their own armies. This perpetual foreign intervention fueled the cycle of local conflict, preventing any single Cretan power from achieving stability and hegemony.

The Pirate’s Haven

In the turbulent, contested seas of the Hellenistic Mediterranean, Crete gained a notorious reputation as a primary base for pirates. This was not merely the work of independent freebooters; piracy was an extension of state policy. Cretan cities, lacking powerful navies for formal warfare, sponsored piratical raids against the shipping and coastlines of their rivals.

This activity was a logical and profitable adaptation of Crete’s long-standing military traditions. The skills of ambush, swift raiding, and naval expertise, honed over centuries of inter-city conflict and mercenary service, were perfectly transferable to piracy. In a geopolitical environment where no single power could police the seas and where the great kingdoms themselves sometimes employed pirates as irregular naval forces, piracy became a lucrative enterprise. It was a primary engine of the Hellenistic economy, supplying the massive demand for slaves in markets across the Aegean and generating plunder that funded the cities’ endless wars. This state-sanctioned piracy, however, would ultimately prove disastrous, as it directly threatened the interests of the Mediterranean’s rising superpower, Rome, and made a Roman intervention inevitable.

Towards Unification?: The Cretan Koinon

In a belated response to the escalating chaos, many Cretan cities joined together to form a loose federation known as the Koinon of the Cretans. This league provided a framework for diplomacy and aimed to promote cooperation and peace. However, it was ultimately too weak to overcome the deep-seated rivalries among its powerful members and failed to end the cycle of internal warfare that was tearing the island apart.

The Cities

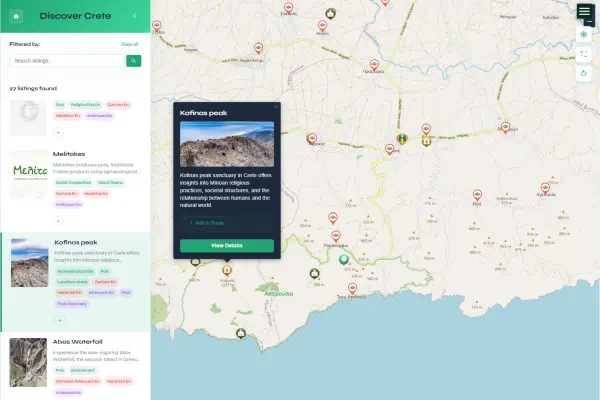

During the Hellenistic period, Crete was divided into numerous city-states, each with its own laws, government, and institutions. Some of the most prominent cities during this time included:

- Knossos

- Gortyn

- Lyttos

- Hierapytna

- Kydonia (Chania)

- Hyrtakina

- Polyrrhenia

- Eleutherna

- Olous

- Praisos

- Itanos

- Lappa

These cities were often engaged in power struggles and conflicts, as they sought to expand their territories and influence.

Economy

The Cretan economy during the Hellenistic period was largely based on agriculture and trade. The fertile plains and valleys of the island produced a variety of crops, including grain, olives, and grapes. The Cretans also raised livestock, such as sheep, goats, and pigs.

Trade was an important part of the Cretan economy, as the island was strategically located on the trade routes between Greece, Egypt, and Asia Minor. Cretan cities exported agricultural products, timber, and other goods to these regions. They also imported luxury items, such as pottery, jewelry, and textiles.