The Enduring Spirit of Cretan Resistance

The Strategic Heart of the Mediterranean

Crete’s geography has made it a strategic location in the Eastern Mediterranean for thousands of years. Its position at the commercial crossroads of the West and the Near East made it a valuable territory for any power seeking to control the region’s sea lanes and trade routes. This constant strategic importance explains its long history of foreign rule and, as a result, its long history of resistance. For the Republic of Venice, Crete, known as the Regno di Candia, was the most important part of its overseas empire, the Stato da Màr, and was necessary for protecting its trade connection to the Levant. For the Ottoman Empire that came after, the island was an important military base, a defense against Christian naval power, and a location for extending its own influence. For the Great Powers of the 19th century, it was a key factor in the politics of the “Eastern Question”. This ongoing strategic importance meant that Crete was rarely independent, and it also shaped a society defined by its continuous struggle against foreign control.

From Byzantine Province to Venetian Colony

The long period of Cretan revolutions began with a transaction that made the local population view foreign rule as illegitimate from the start. After the Fourth Crusade and the fall of Constantinople in 1204 CE, the Byzantine Empire was divided among the victorious Latin crusaders. Crete was initially given to Boniface of Montferrat, a leader of the Crusade. Lacking the ships to secure the island, he sold his claim to the Republic of Venice for 1,000 silver marks in August 1204 CE.

This sale treated the island and its people as property. It separated Crete from its long-standing political and cultural connection to Constantinople, where it had been a part of the Byzantine world since Arab forces were finally removed in 961 CE. The establishment of Venetian authority was the creation of a colonial government whose main purpose was the economic use of the island to benefit Venice. This act of purchase, rather than a traditional conquest, created strong resentment among the Cretan people and their local leaders, which became the basis for nearly five centuries of resistance.

The Evolving Nature of Revolution

The history of Cretan resistance shows an evolution in motive and goals over time. The revolts on the island can be separated into two periods, defined by the ruling power and the objectives of the rebels. The Cretan struggle transformed from conflicts led by aristocrats for social privileges under the Venetians to a unified, national fight for union (Enosis) with Greece under the Ottomans.

The uprisings during the Venetian era (1204-1669 CE) were primarily social in nature. They were driven by the practical ambitions of the island’s noble families, the archontes, not by Greek nationalism. These Greek-Byzantine aristocrats lost their lands and authority under the Venetian feudal system and fought to maintain their social status within the colonial power structure. Their revolts were a form of political negotiation, often concluding with treaties that granted them land and titles in exchange for loyalty to Venice.

In contrast, the uprisings of the Ottoman period (1669-1913 CE) were national liberation movements. Ottoman rule, with its heavy taxes and policy of Islamization, created a significant religious and cultural divide. This strengthened a unified Cretan-Hellenic identity in opposition to the Muslim rulers. The objective was no longer to gain feudal privileges but to remove the foreign government and integrate the island into the newly formed Greek state. This was a struggle for national self-determination to join the modern Greek nation, which lasted for over two centuries until it was successful in 1913 CE.

The Age of the Archons: Revolutions under Venetian Rule (1204-1669)

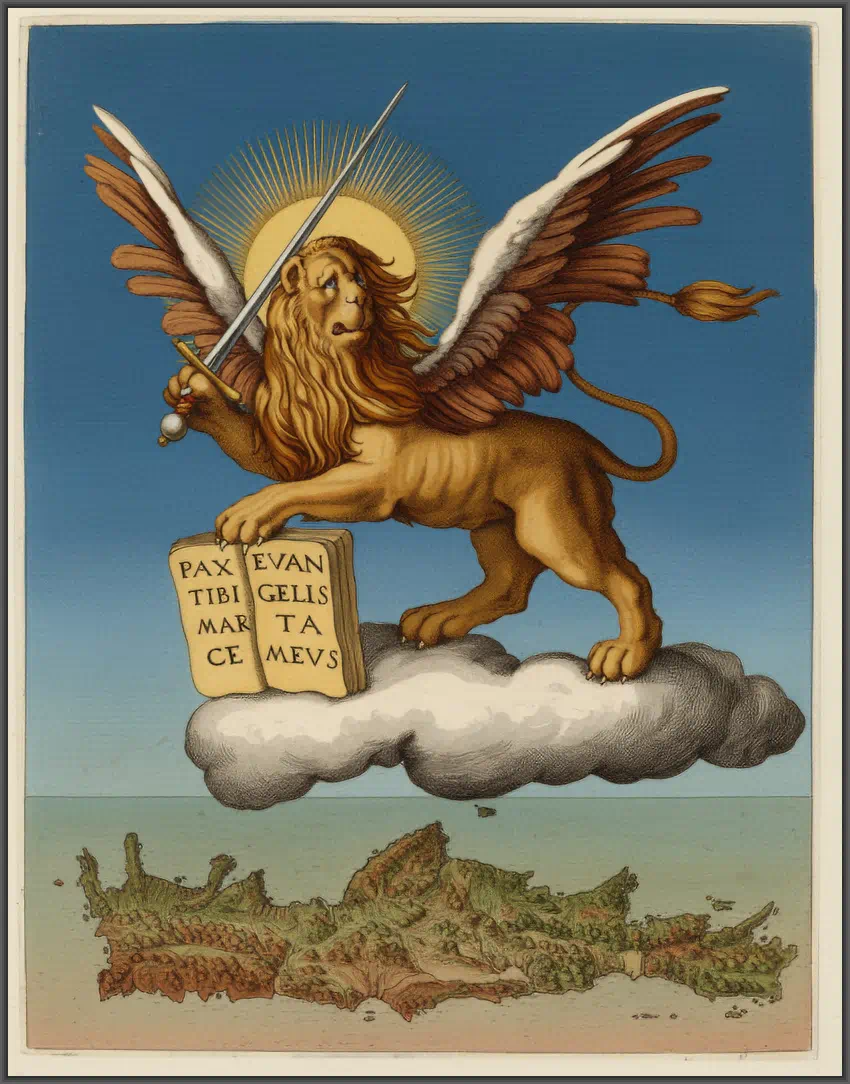

An engraving by the Venetian artist Marco Boschini depicts the Lion of Saint Mark standing over a map of Crete. Created in 1651 for Boschini’s book “Il Regno Tutto di Candia” (The Entire Kingdom of Candia).

Symbolism of the Lion of Saint Mark

The depiction of the Lion of Saint Mark in this engraving is rich with meaning:

- The Wings: The wings signify the divine blessing and protection of Saint Mark, the patron saint of Venice. They elevate the lion from a mere terrestrial beast to a symbol of spiritual authority and power.

- The Open Book: The book held by the lion is inscribed with the Latin phrase “PAX TIBI MARCE EVANGELISTA MEVS,” which translates to “Peace to you, Mark, my Evangelist.”

- The Sword: The prominently displayed sword represents Venice’s military might and its readiness to defend its territories.

- The Halo: The halo encircling the lion’s head further emphasizes the religious and sacred nature of Venice’s dominion, sanctioned by its patron saint.

Venetian rule in Crete, which lasted for 450 years, had several major rebellions, particularly during the first 150 years. These were not continuous wars for national freedom but a repeating cycle of resistance by nobles, suppression by Venice, and political agreements. The local Cretan nobility, the archontoromaioi, who were descendants of Byzantine nobles, had their power and property taken by the new colonial government. They fought back, not always to remove the Venetians entirely, but to force Venice to recognize their status and give them a share of the island’s power and wealth. In turn, Venice used a strategy that mixed military action with political cooperation, gradually making its strongest opponents into partners in the Venetian colonial system.

The Establishment of Venetian Dominion and Early Cretan Resistance (1211-1261)

The Venetian Conquest and Colonization

The Venetian takeover of Crete was neither immediate nor uncontested. Following the purchase of the island in 1204, Venice’s first challenge came from its perennial maritime rival, the Republic of Genoa. The Genoese pirate and Count of Malta, Enrico Pescatore, with the support of the local population, seized control of central and eastern Crete in 1206 and held it for several years. It was not until 1217, after a prolonged and costly war, that Venice finally secured the island, evicting the last Genoese holdouts.

To consolidate its rule over a hostile population, Venice implemented a systematic policy of military colonization. The first wave of colonists, comprising 132 nobles (knights) and 48 commoners (foot soldiers), was dispatched from Venice in 1211-1212. Subsequent waves followed in 1222, 1233, and 1252, with the last group founding the city of Chania upon the ruins of ancient Kydonia. By the end of the 13th century, an estimated 10,000 Venetians had settled on the island. These colonists were granted feudal estates (féuda), carved from the most fertile Cretan lands, in exchange for compulsory military service and loyalty to the Republic. This policy served a dual purpose: it created a loyal Latin military class capable of defending the island and suppressing internal dissent, and it systematically dispossessed the native Cretan aristocracy and the Orthodox Church, seizing their lands and wealth. This direct expropriation of property and power was the primary and immediate catalyst for the first wave of Cretan revolts.

The First Revolution (1211)

The very act of colonization provoked the first major uprising. The arrival of the initial Venetian settlers in 1211 and the concurrent “seizure of Church property and wealth from prominent Cretan families” served as the direct cause for rebellion. This was a fundamental challenge to the economic and social foundation of the local elite.

The revolt was led by the Agiostephanites (or Argyropouloi) family, who rallied their forces in the strategic Lasithi plateau. This high, fertile plain, encircled by mountains, offered a natural fortress and a reliable source of provisions, establishing a pattern that would see Lasithi serve as a revolutionary sanctuary for centuries to come. The rebellion spread rapidly throughout eastern Crete, with the insurgents capturing the key Venetian fortresses of Siteia and Mirabello. The Duke of Crete, Iacopo Tiepolo, found his forces insufficient to contain the uprising and was compelled to seek external assistance from Marco Sanudo, the formidable Duke of the Aegean. Sanudo, an ambitious Venetian nobleman who had carved out his own island empire in the Cyclades, intervened with a strong military force and successfully suppressed the revolt. However, the aftermath revealed the complex rivalries among the Latin rulers themselves, as Tiepolo and Sanudo subsequently fell into a four-year-long conflict over the promised rewards for Sanudo’s intervention.

The Revolutions of the “Two Syvritos” (1217-1228)

The two decades that followed were dominated by a series of three fierce revolts that were instrumental in shaping the long-term relationship between the Cretan aristocracy and their Venetian overlords. These uprisings originated in the mountainous and fiercely independent provinces of Rethymno known as Apano Syvritos (Upper Syvritos, in the Amari Valley) and Kato Syvritos (Lower Syvritos), rugged regions that, like Sfakia and Lasithi, were natural strongholds for guerrilla warfare.

The revolts were spearheaded by two of the most powerful Cretan noble families, the Skordilides and the Melissinoi. The first revolt (1217-1219) was triggered not by a grand political grievance but by a personal affront that underscores the honor-bound nature of aristocratic society. The Venetian castellan of Monopari fortress, Pietro Filicanevo, allowed his men to steal horses and livestock from the estates of the Skordilides family. When the notoriously harsh Duke Paolo Quirino failed to deliver justice, the families rose in revolt under the leadership of Konstantinos Sevastos Skordilis and the brothers Theodoros and Michail Melissinos. After the Venetian forces suffered repeated defeats, the Republic recognized that military suppression was untenable. Quirino was replaced by the more diplomatic Domenico Delfino, who negotiated a treaty on September 13, 1219. This treaty established a crucial precedent: in exchange for an oath of loyalty, the rebel leaders were granted knightly feuds and other privileges, effectively integrating them into the Venetian feudal system. The revolt had become a successful, albeit violent, means of negotiation.

This pattern repeated itself. A new wave of Venetian settlers in 1222 sparked a second, brief revolt led by the Melissinoi brothers, which ended with a 1223 treaty granting them two additional feuds. A third, more widespread revolution erupted in 1228, with the Skordilides and Melissinoi being joined by the Arkoleoi and Drakontopouloi families. This conflict took on a significant geopolitical dimension when the Cretan leaders appealed for aid to the Byzantine Emperor-in-exile at Nicaea, John III Doukas Vatatzes. The emperor, eager to challenge Venetian power, responded by sending a fleet of 33 ships and a military contingent to the island. Despite initial successes, including the capture of several fortresses, the Byzantine fleet was threatened by superior Venetian naval power and withdrew. The revolt concluded with a series of treaties in 1234 and 1236, which again granted more feuds and privileges to the Cretan archons, solidifying their status as a recognized, landed nobility within the Regno di Candia. These early revolts were not primarily about national liberation but were a pragmatic struggle by the dispossessed Archontoromaioi to reclaim their power and property within the new Venetian feudal framework. Venice, for its part, astutely recognized that co-opting these powerful local leaders was more effective in the long run than attempting to annihilate them, a strategy that would ensure a degree of stability for centuries.

The Revolution of 1261

The character of Cretan resistance shifted markedly in 1261. The recapture of Constantinople from the Latins by the Nicaean general Alexios Strategopoulos and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos sent a shockwave through the Greek world. For the first time since the Venetian conquest, the prospect of reunification with a restored and legitimate Byzantine Empire seemed possible. This event directly inspired a new revolt in Crete, which took on a distinctly “national character”.

Emperor Michael VIII, seeking to reclaim lost imperial territories, dispatched an envoy named Stengos to Crete to foment rebellion. Stengos made contact with leading Cretan nobles, including Georgios Chortatzis and Michael Skordilis Psaromilingos, and the revolt was soon joined by the powerful Skordilides, Chortatzides, and Melissinoi families. The uprising enjoyed broad popular support, as the populace saw in the emperor the legitimate sovereign and the only power capable of restoring the Orthodox Church on the island to its pre-conquest status.

The rebellion raged for four bloody years. However, its ultimate failure was determined by two critical factors. Firstly, Michael VIII, embroiled in conflicts on multiple fronts to secure his newly restored empire, was unable to provide the sustained military support he had promised. Secondly, and more decisively, the most powerful Cretan archon on the island, Alexios Kallergis, refused to join the uprising. Motivated by a desire to protect the extensive privileges he had already secured from Venice, Kallergis maintained an “overtly pro-Venetian stance,” fatally dividing the Cretan leadership. Isolated and without external aid, the rebel leaders were forced to negotiate. The resulting treaty of 1265 granted a general amnesty and confirmed the existing privileges of the Cretan nobles, once again demonstrating the Venetian preference for accommodation over annihilation. The emperor’s envoy, Stengos, was granted safe passage from the island, and Michael VIII was compelled to formally recognize Venetian sovereignty over Crete. The revolt of 1261, while ultimately unsuccessful, revealed the deep-seated loyalty of many Cretans to the Byzantine imperial idea and highlighted the critical role that internal divisions, particularly the pragmatism of the Kallergis clan, would play in the future of Cretan resistance.

The Great Revolts and the Rise of the Kallergis Clan (1272-1299)

The last three decades of the 13th century were dominated by two of the largest and most significant rebellions in the history of Venetian Crete. These conflicts marked a turning point, leading to the final suppression of widespread, ideologically-driven national revolts and culminating in a landmark political settlement that would define the relationship between Venice and the Cretan aristocracy for the next century. Central to this entire period was the towering and ambiguous figure of Alexios Kallergis, a master of power politics who was, at different times, both Venice’s greatest ally and its most formidable foe.

The Revolution of the Chortatzides Brothers (1272-1278)

Described as the “first major revolution of a national character,” the Chortatzides uprising was not sparked by a dispute over feudal privilege but by an act of blatant injustice that inflamed popular sentiment. The murder of a Greek by two Venetians in Chandax (Heraklion), for which the authorities failed to provide redress, ignited a widespread revolt. This shift from aristocratic grievance to a broader sense of communal outrage gave the rebellion its uncompromising, liberationist character.

The leadership was assumed by the brothers Georgios and Theodoros Chortatzis, renowned for their bravery and patriotism. They established their primary base of operations in the defensible highlands of the Lasithi plateau, from where they launched attacks across eastern Crete. The revolt achieved significant successes, including a major victory in the Messara plain where the Duke of Crete himself was killed, and Georgios Chortatzis even managed to lay siege to the capital, Chandax.

The ultimate failure of this powerful movement can be attributed directly to the calculated actions of Alexios Kallergis. Seeking to eliminate his chief rivals and establish himself as the sole, undisputed leader of the Cretan people, Kallergis made a strategic alliance with the Venetians. He raised an army of his own followers and mercenaries and joined the Venetian forces in their campaign against the Chortatzides. The combined army decisively defeated the rebels near Hersonissos, forcing them back to their mountain strongholds. The combination of internal betrayal, a lack of supplies, and the arrival of fresh Venetian troops under a new duke, Marino Gradenigo, led to the final suppression of the revolt in 1278. Unlike previous uprisings, this one did not end in a negotiated treaty. Its explicitly national and liberationist aims were incompatible with compromise. The Chortatzides brothers were declared outlaws and, to escape capture, fled to Asia Minor. Venice unleashed a wave of “terrible and harsh reprisals” to make an example of the rebels and deter future uprisings. Through his collaboration, Alexios Kallergis had successfully eliminated his main competitors, leaving him as the preeminent Cretan archon, the “undisputed master of the island”.

The Revolution of Alexios Kallergis (1282-1299)

In a remarkable turn of events, just four years after helping Venice crush the Chortatzides, Alexios Kallergis himself instigated the “fiercest and largest-scale revolution of the Cretan aristocracy against the Venetians”. The primary cause was Venice’s attempt to curtail the immense power that Kallergis had accumulated—a power they themselves had helped to create. Having used him to eliminate their other enemies, the Venetians now saw Kallergis as a threat to their own authority.

The timing of the revolt was also significant. It began in 1282, the same year as the Sicilian Vespers, a massive uprising that expelled the Angevin French from Sicily and threw the geopolitical balance of the Mediterranean into turmoil. It is highly probable that the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, a master of diplomacy and intrigue, encouraged Kallergis’s revolt as a strategic diversion to keep Venice, a potential ally of the Angevins, occupied and prevent it from intervening in Sicily.

The revolution, which lasted for an unprecedented 17 years, was a grueling war of attrition. Led by Kallergis from his family stronghold in the province of Mylopotamos, and supported by other prominent families such as the Varouches, Gavalades, and Vlastoi, the conflict took the form of widespread guerrilla warfare. The Venetians responded with brutal tactics, destroying monasteries, torturing prisoners, and declaring the revolutionary heartland of the Lasithi plateau an uninhabited zone, even forbidding the grazing of flocks there. Despite a decade of inconclusive battles and continuous Venetian reinforcements, no decisive outcome was achieved. A critical moment came in 1296 when the Genoese admiral Lamba Doria attacked and burned Chania, attempting to form an alliance with Kallergis. However, Kallergis, perhaps seeing the war had reached a stalemate and leaning towards a settlement with Venice, refused to join forces with the Genoese.

After nearly two decades of exhausting conflict, both sides were ready for a settlement. The result was the “Peace of Alexios Kallergis,” a landmark treaty signed on April 28, 1299, that fundamentally reshaped the political landscape of Crete. This was not a mere surrender or a simple grant of amnesty; it was a comprehensive political accord that institutionalized the power of the Kallergis family as the de facto co-rulers of the island’s Orthodox population. The key terms of the 33-article treaty were extraordinary :

- Territorial and Feudal Power: Kallergis was not only granted amnesty and the return of all his confiscated lands but was also given four additional knightly feuds. Crucially, he was granted the right to bestow feuds and privileges upon his own followers, a power previously reserved for the Venetian Duke.

- Social and Legal Rights: Intermarriage between Cretans and Latins was officially permitted, breaking down a key barrier of the colonial system. Furthermore, the decisions of the courts that Kallergis had established in rebel-held territory during the war were recognized as valid.

- Religious Authority: In a major concession, Kallergis was granted the right to appoint an Orthodox bishop to the Diocese of Arios (which was renamed Kallergoupolis) and to lease the revenues of other dioceses. This effectively made him the official patron and protector of the Orthodox Church in a large part of Crete.

The “Pax Alexii Callergi” (April 28, 1299)

The “Pax Alexii Callergi” was a masterstroke of Venetian pragmatism. By formally recognizing Kallergis as the hereditary leader of the Orthodox Cretans and deeply integrating him and his family into the colonial power structure, Venice transformed its most dangerous adversary into its most powerful local ally. The treaty was so effective that it stabilized Venetian-Cretan relations for a century. Kallergis and his descendants became guarantors of the Venetian order, and as the subsequent revolts of the 14th century would show, the Kallergis family would more often be found suppressing rebellions than leading them. The era of large-scale, unified aristocratic revolts was effectively over.

Shifting Alliances and Internal Strife in the 14th Century

The 14th century marked a significant shift in the dynamics of Cretan resistance. The comprehensive settlement of the “Pax Alexii Callergi” had successfully co-opted the most powerful Cretan family into the Venetian power structure, effectively neutralizing the main engine of the great 13th-century rebellions. Consequently, the resistance movements of this period were more fragmented, often characterized by internal divisions within the Cretan nobility itself, and even saw the unprecedented spectacle of Venetian colonists rebelling against their own motherland.

The Kallergis Dynasty in Conflict

The success of Venice’s strategy was immediately apparent. The Kallergis family, now bound by treaty and privilege to the Venetian regime, became an instrument for suppressing further dissent.

- The Sfakia Revolution (1319): This uprising began in the perennially rebellious region of Sfakia, a mountainous and inaccessible area whose inhabitants had never been fully subjugated. The cause was a classic matter of aristocratic honor: a Venetian castellan named Capelletto insulted a daughter of the powerful Skordilides family, reportedly by cutting her hair after she rebuffed his advances. Her relatives retaliated by killing the castellan and his garrison, sparking a revolt. The rebels fortified themselves in the Samaria Gorge, but the uprising was decisively crushed with the active military assistance of Alexios Kallergis, who honored his treaty obligations to Venice.

- The Revolution of Vardas Kallergis (1333-1334): This revolt demonstrates the deep fractures that were beginning to appear within the Kallergis clan itself. It was sparked by the imposition of a new extraordinary tax by Duke Viago Zeno to fund the construction of galleys for anti-piracy operations. The protest began in the village of Margarites in Mylopotamos and was led by a dissident member of the family, Vardas Kallergis, along with Nikolaos Prikosiridis and the Syropouloi brothers. In a stark display of the family’s divided loyalties, the revolt was suppressed with the “highly treacherous” help of Georgios Kallergis, the son and heir of Alexios. The rebellion was crushed in 1334, its leaders were executed, and their families were exiled.

- The Revolution of Leon Kallergis (1341-1347): Another uprising was led by a patriotic member of the family, Leon Kallergis, who secretly instigated a revolt in Apokoronas and Sfakia. He garnered support from major traditional families, including the Melissinoi, Skordilides, and Psaromilingoi. However, the movement was betrayed. Leon was captured by the Venetians through trickery and executed by being thrown into the sea in a sack. The rebellion was continued with great passion by his relatives, the brothers Ioannis and Michail Psaromilingoi (also known as the Kapsokalyves). After a series of fierce battles, the revolt was finally crushed in a decisive battle in the Messara plain in 1347, where Ioannis was killed and Michail, wounded, ordered his own decapitation to prevent being captured alive.

The Apostasy of Saint Titus (1363-1366)

This engraving, titled “Leonardo Dandolo che tenta coraggiosamente di sedare i ribelli di Candia (9 Agosto 1363),” which translates to “Leonardo Dandolo courageously attempting to quell the rebels of Candia (9 August 1363),” captures a pivotal moment in the history of Venetian-ruled Crete.

The artist, G. Letterini, has dramatized the scene to emphasize the bravery of the Venetian governor in the face of a dangerous insurrection. The work is part of a series on Venetian history (“histoire venitienne”), and as such, it tells the story from a Venetian perspective, highlighting the courage of its representative.

One of the most remarkable events in the history of Venetian Crete was a rebellion initiated not by the native Greeks, but by the Venetian feudal colonists themselves. Known as the Revolt or Apostasy of Saint Titus, this uprising revealed the emergence of a distinct colonial identity among the Venetian settlers, whose local interests had begun to diverge from those of the metropolis.

The primary cause was economic. The Venetian feudal lords in Crete felt they were being oppressed by heavy taxation imposed by Venice and that they were treated as second-class nobles compared to the aristocracy of the mother city. The final trigger was a new tax levied in 1363 to finance repairs to the port of Candia (Heraklion). The feudatories, led by the prominent Gradenigo and Venier families, refused to pay, arrested the Venetian Duke Leonardo Dandolo, and declared Crete an independent republic under the patronage of the island’s patron saint, Saint Titus—the “Republic of Saint Titus”.

To secure the crucial support of the Greek population, the Venetian rebels made unprecedented concessions. They allied with Cretan nobles, including the Kallergides, and promised full equality between the Orthodox and Catholic Churches, abolishing all restrictions on the ordination of Orthodox priests. This alliance of Latin colonists and Greek natives against the central government was a profound shift in the island’s social dynamics. However, the independent republic was short-lived. Venice, viewing the secession of its most valuable colony as an existential threat, responded with overwhelming force. A large expeditionary army of mercenaries was dispatched, which landed in May 1364 and recaptured Candia with little resistance. The leaders of the revolt were summarily executed, and their families were stripped of their nobility and exiled.

Revolution of the Kallergides (1364-1367)

The suppression of the Venetian colonists’ revolt did not end the conflict. The Cretan nobles who had allied with them, primarily the Kallergis brothers (Ioannis, Georgios, and Alexios), were declared outlaws with bounties on their heads. They responded by launching a new revolution in August 1364, which was a direct continuation of the previous struggle but now had a purely Greek and nationalist character. The rebels fought under the Byzantine flag, proclaiming their goal was liberation from Latin rule.

The revolt began in Mylopotamos and quickly spread throughout the island. The rebels gained control of most of western Crete and even received encouragement from the Byzantine Emperor John V Palaiologos, who sent the Metropolitan of Athens, Anthimos, to the island as “President of Crete”. Venice, however, reacted with utmost determination. The Pope declared the war a crusade, and a massive military force, including Turkish mercenaries, was sent to the island. The war devolved into a brutal guerrilla conflict. Despite their tenacity, the rebels were worn down by famine and superior Venetian resources. After the Venetian leaders of the previous revolt were captured and executed, the rebellion was contained to its last stronghold: the mountains of Sfakia. In April 1367, a Venetian force crossed the mountains and, through betrayal, captured the Kallergis leaders. The Venetian retribution was horrific. The captured leaders were executed, and Anthimos was imprisoned, dying from his hardships in 1371. In an act of collective punishment, Venice ordered the complete evacuation of key rebel centers, including the Lasithi plateau and Anopolis in Sfakia. This brutal and final suppression marked the definitive end of the era of great Cretan revolutions against Venice.

The Twilight of Venetian Rule: Conspiracies and Final Uprisings

After the crushing defeat of the Kallergides in 1367, the nature of Cretan resistance underwent a fundamental change. The era of large-scale, aristocratic-led military campaigns came to an end. The subsequent period was marked by a long interval of relative peace and economic prosperity, but the spirit of resistance did not disappear entirely. Instead, it was channeled into clandestine conspiracies, often inspired by the fading memory of the Byzantine Empire, and smaller, more localized popular uprisings.

Echoes of Byzantium (1453-1460)

The final Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 was a traumatic event for the entire Orthodox world, but it had a particularly profound impact on Crete, which was now one of the last major Greek-speaking territories under Christian rule. The event extinguished the last glimmer of hope for external liberation by a restored Byzantine Empire, a hope that had fueled many of the earlier revolts. In this new geopolitical reality, resistance became more ideological and desperate, taking the form of secret plots rather than open warfare.

- The Conspiracy of Sifis Vlastos (1453-1454): Just months after the fall of the Byzantine capital, a conspiracy was organized in Rethymno with the explicit goal of “reviving the Byzantine imperial idea”. The movement was not a popular uprising but a clandestine plot led by Sifis Vlastos, a man of significant local influence from a noble Rethymniot family. His collaborators included several Orthodox priests, such as Manassis Arkoleos and Pavlos Kalyvas, and other nobles, including Georgios Kallergis. The conspiracy was also a reaction against Venetian pressure to enforce the Union of the Churches decided at the Council of Florence, a policy deeply resented by the Orthodox clergy and populace. However, before the plan could be put into action, it was betrayed to the Venetian authorities by a priest, Ioannis Limas, and a Venetian citizen. The leaders were swiftly arrested in August 1454, tortured, and executed. As a punitive measure, Venice forbade the ordination of any new Orthodox priests for five years.

- The Conspiracy of 1460: A few years later, another conspiratorial movement emerged in Rethymno, involving the protopapas (archpriest) of the city, Petros Tzagkaropoulos, and refugees who had fled the Ottoman advance in mainland Greece. This plot also had an irredentist character, fueled by the influx of those who had lost their homes to the Turks. Like its predecessor, it was betrayed—by a Jewish man, David Mavrogonatos, and a Greek collaborator, Ioannis Limas—and the conspirators were arrested and executed before their plans could materialize.

The Last Stand: Revolution of Georgios Kantanoleon (1523-1527)

The last major revolutionary effort during the Venetian period marked a significant shift from the aristocratic conspiracies of the 15th century. The revolt of Georgios Kantanoleon, also known as Lysogiorgis, was not primarily an ideological movement but a popular uprising rooted in the economic grievances of the rural population. It represented a fusion of resistance from the “agrarian and pastoral populations” of western Crete against oppressive taxation and the various abuses of local Venetian officials.

The rebellion began in 1523 in the region of Kerameia, near Chania, with a force of 600 armed men. It quickly spread to the traditional heartlands of Cretan resistance, including Sfakia, Selino, and the mountainous areas of Kydonia. For several years, the rebels waged a guerrilla war against Venetian forces. The conflict came to a head in October 1527, when the Venetians launched a major military campaign to suppress the uprising. Within a month, the revolt was crushed. The Venetian retribution was characteristically swift and brutal. Entire villages that had supported the rebellion, such as Kerameia, Alikambos, and Meskla, were razed to the ground. Kantanoleos was captured through betrayal and executed. Thousands of inhabitants from the rebellious regions were exiled to prevent future uprisings. This revolt, with its popular, agrarian base, signaled the end of an era where rebellions were the exclusive domain of archons fighting for feudal rights. It foreshadowed the character of the future, broader-based national struggles that would come to define the Ottoman period.

The Struggle for Union (Enosis): Revolutions under Ottoman Rule (1669-1913)

The fall of Candia (Heraklion) to the Ottoman Empire in 1669 after a grueling 21-year siege marked the end of 465 years of Venetian rule and ushered in a new, harsher era of foreign domination. The nature of Cretan resistance was fundamentally transformed. The old struggles of the archons for feudal privileges within a shared Christian-Latin framework gave way to a unified, popular, and explicitly nationalistic fight for liberation and union (Enosis) with the emerging Greek nation-state. This new phase of revolution was defined by a shared Hellenic identity forged in opposition to Ottoman rule, the deep societal cleavage created by Islamization, and the complex geopolitical machinations of the European Great Powers as they contended with the decline of the Ottoman Empire—the so-called “Eastern Question.”

The Ottoman Conquest and the First Major Uprising

The Ottoman Conquest and the Nature of Turkish Rule

The Ottoman conquest plunged Crete into what was described as a “most onerous” servitude (epachthestati douleia). While Venetian rule had been exploitative, Ottoman administration introduced a new and profound challenge to Cretan identity: a policy of widespread Islamization. Economic and social pressures, including heavy taxation and the promise of privilege, led a significant portion of the Cretan population to convert to Islam over the subsequent centuries. This created a new social class known as “Turkocretans”—native, Greek-speaking Cretans who had adopted the Muslim faith. This religious division created a deep and often violent schism within Cretan society itself, transforming the struggle against foreign rule into a conflict that was simultaneously a national, religious, and at times, civil war. The distinction was no longer between Latin Catholic rulers and Greek Orthodox subjects, but between Greek Christians and a ruling power whose local representatives were often their former neighbors and kin. This dynamic imbued the subsequent revolutions with a new intensity and a clear, unifying goal: the preservation of their Christian faith and Hellenic identity through union with a free Greece.

The Daskalogiannis Revolt (1770-1771)

The first major uprising against Ottoman rule was not a spontaneous local affair but was directly instigated by external geopolitical forces. The revolt was an integral part of the Orlov Revolt (the Orlofika), a broader Russian-sponsored rebellion across the Greek lands intended to create a diversion during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774.

The leader of the Cretan front of this rebellion was Ioannis Vlachos, a wealthy and educated shipowner from the village of Anopolis in Sfakia. His learning earned him the name Daskalogiannis (“Teacher John”). During his travels, he came into contact with Russian emissaries, who persuaded him to lead an uprising in Crete with the promise of substantial Russian military and naval support.

The revolt was centered in the fiercely independent and rugged region of Sfakia, a mountainous bastion that had never been fully subjugated by either the Venetians or the Ottomans, making it the natural heartland for any Cretan rebellion. In the spring of 1770, Daskalogiannis, having gathered a force of around 2,000 men, refused to pay taxes and launched attacks against Turkish settlements in the surrounding provinces.

Despite some initial successes, the promised Russian fleet and soldiers never materialized. Left to face the full might of the Ottoman Empire alone, the Cretan cause was doomed. The Ottomans assembled an overwhelming force of 15,000 soldiers, which invaded and systematically devastated Sfakia, burning villages and enslaving the population. Faced with the annihilation of his people and hoping to secure lenient terms, Daskalogiannis made the fateful decision to surrender under a promise of amnesty. He was taken to Heraklion (Chandax), where the promise was betrayed. On June 17, 1771, he was publicly and brutally executed by being flayed alive, an act of terror designed to crush the Cretan spirit.

The Daskalogiannis revolt, though a catastrophic failure in military terms, was a pivotal moment. It marked the definitive entry of the Cretan struggle into the broader arena of European geopolitics and taught the Cretans a bitter but valuable lesson about the unreliability of foreign powers whose strategic interests did not align with their own. More importantly, the horrific martyrdom of Daskalogiannis transformed him into a foundational hero of the modern Cretan national identity. His sacrifice, immortalized in folk songs and oral tradition, became a powerful symbol of resistance and self-sacrifice for the national cause, providing a potent source of inspiration for the generations of revolutionaries who would follow in the 19th century.

Crete in the Greek War of Independence (1821-1830)

The outbreak of the Greek War of Independence on the mainland in March 1821 inevitably and immediately spread to Crete. The island’s participation was not merely a peripheral theater but an integral and particularly bloody chapter of the national struggle. The Cretan revolution of 1821-1830 mirrored the broader conflict in its patterns of popular uprising, brutal reprisals, internal political factionalism, and attempts at modern state-building. However, its fate would ultimately be decided not by the immense sacrifices on the island, but by the cold calculus of Great Power geopolitics.

The Spark of Revolution (1821)

The revolutionary ideals that had been brewing on the mainland were actively disseminated in Crete by the Filiki Eteria (Society of Friends), the secret society that orchestrated the national uprising. Emissaries such as Emmanouil Vernardos traveled to the island to initiate prominent local leaders into the conspiracy. Among the most significant of these was Michail Kourmoulis, a powerful leader from Messara who was a “crypto-Christian”—a member of a family that had converted to Islam for social and economic reasons but secretly maintained its Christian faith and Greek identity. The willingness of figures like Kourmoulis to throw off their public disguise and join the rebellion highlights the deep-seated Hellenic consciousness that transcended religious lines.

Following preparatory assemblies in the traditional revolutionary heartland of Sfakia in April 1821, the war was officially declared on June 14, 1821, with an initial Cretan victory in a skirmish at Loulo, near Chania. The flame of revolution quickly spread throughout the island.

A War of Atrocities and Key Battles

The Ottoman response was immediate and savage, targeting both the clergy and the civilian population in an effort to terrorize the Greeks into submission. On June 19, the Bishop of Kissamos, Melchisedek Despotakis, was hanged in Chania. This was followed by the infamous “Great Arpentes” (the great slaughter) in Heraklion on June 24, 1821. An incited Muslim mob stormed the metropolitan cathedral, murdering the Metropolitan of Crete, Gerasimos Pardalis, along with five other bishops who had been summoned to the city and held as hostages. The massacre claimed over 800 Christian lives in and around the city.

Despite these atrocities, the rebellion gained momentum. Fierce battles raged across the island, particularly in the western provinces of Kerameia, Malaxa, Apokoronas, and Lakkoi, where Cretan chieftains like Georgios Daskalakis (Tselepis) and the Chalis brothers led their forces to several notable victories against the Turks of Chania and Rethymno. The mountainous terrain, familiar to the Cretan fighters and treacherous for the Ottoman regulars, allowed for effective guerrilla warfare.

Forging a State Amidst Chaos

As the revolution progressed, the need for a unified political and military command became apparent. The endemic factionalism among local chieftains, each with their own followers and ambitions, hampered a coordinated war effort. In an attempt to impose central authority, the leader of the mainland revolution, Dimitrios Ypsilantis, appointed Michail Komninos Afentoulis as “General Eparch and Commander-in-Chief of Crete.” Afentoulis arrived in November 1821, but his tenure (November 1821 – November 1822) was fraught with difficulty. A stranger to the island’s complex social dynamics and perceived as arrogant, he clashed repeatedly with the powerful Sfakian captains and suffered a number of military setbacks, including a failed siege of Rethymno in March 1822.

Despite these internal conflicts, a landmark attempt at modern state-building occurred in May 1822. A General Assembly of Cretans, comprising 40 representatives from across the island, convened in the village of Armenoi, Apokoronas. This assembly drafted and adopted a “Provisional Constitution of the island of Crete,” establishing a framework for a unified administration and formally linking the Cretan struggle to the provisional government on the mainland. This act demonstrated a clear political objective beyond mere rebellion: the creation of a modern, organized polity intended to be part of a free Greece.

The Egyptian Intervention (1822-1824)

By 1822, the Sultan, Mahmud II, unable to quell the rebellion with his own forces, was compelled to seek the aid of his powerful and ambitious vassal, Muhammad Ali of Egypt. In exchange for territorial gains, Muhammad Ali dispatched a modern, European-trained army and fleet to Greece. In May 1822, a formidable Egyptian fleet under the command of Hasan Pasha landed at Souda Bay, near Chania.

The arrival of the Egyptians dramatically shifted the military balance. Hasan Pasha launched a series of devastating campaigns across the island. His forces sacked and leveled key revolutionary centers, including the mountain village of Anogeia, and in late October 1822, they invaded and systematically destroyed every village on the Lasithi plateau. The Cretans, outmatched by the superior discipline and firepower of the Egyptian army, suffered a series of crushing defeats.

At the Cretans’ request, the unpopular Afentoulis was replaced in late 1822 by Emmanouil Tombazis, a naval captain from Hydra. Despite his efforts to rally the resistance, including holding an assembly at Arkoudaina in June 1823 to reconcile the local captains, the tide was irreversible. The main Cretan force of 3,000 men was annihilated by the Egyptian army, now under the command of Hussein Bey, at the battle of Amourgelles on August 20, 1823. By the spring of 1824, Hussein had suppressed all organized resistance, and Tombazis was forced to flee the island. The first phase of the Cretan revolution had been brutally crushed.

The Geopolitical Aftermath

Although the revolution in Crete was reignited in the later years of the war, its ultimate fate was sealed by the Great Powers (Britain, France, and Russia). Following their decisive intervention at the Battle of Navarino in 1827, which destroyed the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet, the Powers negotiated the terms of Greek independence. The London Protocol of February 1830, which formally established the independent Kingdom of Greece, explicitly excluded Crete, along with other regions with large Greek populations like Samos and Thessaly. In a bitter blow to the Cretans, the island was formally ceded to Muhammad Ali’s Egypt as a reward for his earlier intervention against the Greeks. This decision was a stark illustration of the “Eastern Question” in action. Great Britain, in particular, was adamant about preventing the strategically vital island from becoming part of a new Greek state that it feared would be susceptible to the influence of its rival, Russia. The security of Britain’s sea lanes to the eastern Mediterranean and India took precedence over the principle of self-determination for the Cretan people, whose nine years of immense sacrifice were ultimately ignored in the diplomatic salons of Europe.

The Long 19th Century: A Century of Revolution

The cession of Crete to Egypt in 1830, and its return to direct Ottoman rule in 1840, did not extinguish the Cretan desire for Enosis. Instead, it inaugurated a “long 19th century” of near-continuous revolutionary struggle. A series of major uprisings—in 1841, 1858, the “Great Cretan Revolution” of 1866–69, 1878, and the final revolt of 1897–98—marked an escalating campaign for union with Greece. Each revolt, though often suppressed militarily, created an international diplomatic crisis that forced the Ottoman Empire, under intense pressure from the European Great Powers, to grant ever-greater concessions. This cycle of rebellion and reform moved the island incrementally but inexorably away from Ottoman control and toward autonomy, setting the stage for its eventual unification with Greece. This entire process was deeply embedded in the broader context of the “Eastern Question”—the strategic competition among the Great Powers over the fate of the declining Ottoman Empire.

The Great Cretan Revolution (1866-1869)

The largest and most significant of these uprisings was the Great Cretan Revolution of 1866–1869. Its causes were twofold: the persistent failure of the Ottoman authorities to implement the reforms promised in the 1856 Hatt-ı Hümayun, which guaranteed civil and religious equality for Christians, and a fervent, renewed popular demand for union with Greece.

The revolution began in August 1866 and quickly spread throughout the island’s countryside. While the rebels were unable to capture the fortified northern cities, they established control over the mountainous interior. The defining moment of the revolution, and one that would resonate across the world, was the “Holocaust of Arkadi Monastery” in November 1866. The historic Arkadi Monastery, located near Rethymno, served as a headquarters for the rebellion. An overwhelming Ottoman force of 15,000 men laid siege to the monastery, where 259 fighters, along with over 700 women and children from surrounding villages, had taken refuge. After two days of fierce resistance, as Ottoman troops breached the walls, the defenders made a desperate, heroic choice. Rather than surrender to certain death or enslavement, the rebel leader Kostis Giaboudakis (or, according to other accounts, the abbot) ignited the gunpowder barrels stored in the monastery’s powder magazine. The massive explosion killed almost everyone inside—rebels, women, and children—along with hundreds of the attacking Ottoman soldiers.

This act of mass self-sacrifice, immediately dubbed the “Arkadi Holocaust,” became a powerful symbol of the Cretan struggle for freedom. News of the tragedy, transmitted rapidly by the newly available telegraph, caused a wave of shock and outrage across Europe and the United States. It galvanized philhellenic sentiment, drawing comparisons to the heroic fall of Missolonghi during the 1821 war, and transformed the Cretan revolt from a local conflict into an international humanitarian cause. Public committees were formed in major cities to raise funds and send volunteers, and diplomatic pressure on the Ottoman Empire intensified dramatically.

Although the revolution was eventually suppressed militarily by 1869, the international outcry over Arkadi made a simple return to the status quo impossible. To appease the European powers and pacify the island, the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Âli Pasha, personally oversaw the implementation of the Organic Law of 1868. This new constitution granted Crete a significant degree of self-government, establishing an elected assembly with a Christian majority and giving Christians a substantial role in the local administration. While falling short of Enosis, it was a major political victory won through armed struggle and international public opinion.

The Path to Freedom: The Pact of Halepa and the Cretan State

The Organic Law failed to satisfy the ultimate Cretan aspiration for union, and another major revolt erupted in 1878, timed to coincide with the broader Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78. This uprising again led to the intervention of the Great Powers, who, at the Congress of Berlin, pressured the Ottoman Empire into granting further concessions. The result was the Pact of Halepa in October 1878. This convention significantly expanded upon the Organic Law, granting a wider form of autonomy. It confirmed a Christian majority in the General Assembly, designated Greek as the official language of the assembly and the courts, and granted other financial and administrative freedoms. The Pact of Halepa represented the apex of liberal reform under Ottoman rule and a crucial step toward full self-government.

However, this autonomy was curtailed by the Sultan in 1889 following another period of unrest, leading to the final and decisive uprising of 1897-1898. This revolt was characterized by intense inter-communal violence between Christians and Muslims. The intervention of the Great Powers, who deployed an international naval squadron to blockade the island and occupy the main cities, failed to quell the fighting. The tipping point came in September 1898, when a Muslim mob in Heraklion, angered by the installation of a new customs service, rioted and massacred hundreds of local Christians, as well as the British vice-consul and 14 British soldiers.

This direct attack on European forces provoked an immediate and decisive response. The Great Powers issued an ultimatum to the Sultan, demanding the complete withdrawal of all Ottoman troops and administrators from the island. The Sultan complied, and in November 1898, the last Ottoman soldiers departed. The Powers then established the autonomous Cretan State (Kritiki Politeia). While still under the nominal suzerainty of the Sultan, the island was to be governed by a High Commissioner chosen by the Powers. In a move that made the path to Enosis clear, they appointed Prince George of Greece, the second son of the Greek king, to the post. The Cretan State, with its own government, gendarmerie, and flag, was effectively independent. This arrangement was a classic Great Power solution to a persistent problem within the “Eastern Question,” designed to pacify the region while preserving the fragile fiction of Ottoman territorial integrity. For the Cretans, however, it was merely the penultimate step before the final realization of their century-long struggle.

The Final Union

The establishment of the Cretan State in 1898 was a monumental achievement, but for the vast majority of Cretan Christians, it was an inherently temporary and unsatisfactory solution. Autonomy was not the goal; Enosis was. The final chapter of the revolutionary struggle was dominated by the political maneuvering required to overcome the last diplomatic obstacles to union, a process spearheaded by Crete’s most famous statesman, Eleftherios Venizelos.

The Theriso Revolt (1905)

The government of the Cretan State was placed in the hands of Prince George of Greece, who acted as High Commissioner on behalf of the Great Powers. While his appointment was initially seen as a step toward union, his autocratic style of rule and his perceived failure to advance the national cause quickly brought him into conflict with a faction of Cretan politicians led by Eleftherios Venizelos. Venizelos, who had served as Minister of Justice in the Prince’s government, resigned in 1901 after a series of disagreements over the Prince’s handling of both internal affairs and the question of union.

In March 1905, Venizelos launched the Theriso Revolt. This was not a full-scale war but a political and military challenge to the Prince’s authority. Venizelos and his followers established a rival “provisional government” in the village of Theriso, a traditional revolutionary stronghold in the foothills of the White Mountains. They hoisted the Greek flag and formally proclaimed Crete’s union with Greece, directly defying the authority of the High Commissioner and the mandate of the protecting Powers.

The revolt was a masterstroke of political strategy. Venizelos understood that he could not defeat the international forces militarily. Instead, his aim was to create a political crisis that would make the island ungovernable under Prince George, thereby forcing the Great Powers to reconsider the existing arrangement. The strategy worked. After months of skirmishes between the rebels and the Cretan Gendarmerie (which was supported by Russian troops), and faced with widespread popular support for Venizelos, the Great Powers intervened diplomatically. They negotiated a settlement that, while not granting immediate union, met most of the rebels’ demands. Prince George was forced to resign and was replaced by Alexandros Zaimis, a more moderate Greek politician. A new, more liberal constitution was drafted, and Greeks were permitted to take up officer positions in the Cretan Gendarmerie, further strengthening the island’s ties to the mainland. The Theriso Revolt had successfully removed the primary obstacle to union and made the eventual outcome all but inevitable.

The Balkan Wars and the Realization of a Dream (1912-1913)

The final opportunity for union came with the outbreak of the First Balkan War in October 1912. As an alliance of Balkan states, including Greece, declared war on the Ottoman Empire, the geopolitical landscape of the region was fundamentally altered. With the Ottoman Empire fighting for its survival in Thrace and Macedonia, and with the Great Powers preoccupied by the wider conflict, the diplomatic constraints that had held Crete in a state of autonomy finally dissolved.

Greece acted decisively. The Greek government, now led by Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, formally accepted the Cretan deputies into the Greek Parliament in Athens. The union, unilaterally declared by the Cretans in 1908 but never recognized, was now a political reality. The Great Powers tacitly acknowledged this by lowering their flags from the fortress at Souda Bay on February 14, 1913.

The formal international recognition came with the conclusion of the war. In the Treaty of London (May 1913), the defeated Ottoman Empire was forced to cede Crete, along with its other remaining European territories, to the victorious Balkan allies. Sultan Mehmed V officially relinquished all his rights of sovereignty over the island.

The centuries-long struggle reached its emotional and symbolic climax on December 1, 1913. At the Firka Fortress in Chania, the last vestiges of foreign authority were removed, and the Greek flag was officially raised in the presence of King Constantine I of Greece and Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, the Cretan who had done more than any other to bring about the fulfillment of the national dream. The union of Crete with Greece was finally, and irrevocably, complete.

From Feudal Ambition to National Identity

The seven-hundred-year saga of the Cretan revolutions represents one of the most sustained and tenacious struggles for freedom in European history. It is a narrative of profound evolution, tracing the transformation of a society’s motivations for resistance from the pragmatic and self-interested ambitions of a feudal aristocracy to the all-consuming and deeply ideological pursuit of national self-determination.

The early revolts against the Republic of Venice were, at their core, a violent negotiation for power and privilege. The Cretan archontes, the descendants of the Byzantine nobility, fought not to expel their new Latin masters but to force their way into the colonial power structure. Their rebellions were transactional; victory was measured in the acquisition of feuds, titles, and tax exemptions, as codified in the series of treaties that punctuated the 13th and 14th centuries. Venice, a pragmatic maritime empire, understood this dynamic and skillfully employed a strategy of co-option, transforming its most dangerous adversaries into vested stakeholders of the Regno di Candia. The “Pax Alexii Callergi” of 1299 stands as the ultimate expression of this policy, a settlement that purchased stability by granting immense power to a single Cretan family, effectively turning the leader of the resistance into a guarantor of the colonial order.

The Ottoman conquest in 1669 irrevocably altered this calculus. The imposition of a non-Christian ruling power and the subsequent policy of Islamization created a stark and non-negotiable divide. Resistance was no longer a matter of social status but of existential survival—the preservation of religious faith, cultural heritage, and Hellenic identity. The struggle against the Ottomans was, from the outset, a national one. The goal was not accommodation but liberation; the desired outcome was not a place within the imperial system but the complete dissolution of that system and union (Enosis) with the nascent Greek nation-state.

The revolts of the Ottoman period, from the tragic sacrifice of Daskalogiannis to the final, successful uprising of 1897, were chapters in a single, continuous war for national union. The Cretan revolutionaries learned to fight on two fronts: with guerrilla warfare in the island’s formidable mountains and with savvy diplomacy in the courts of Europe. They leveraged the strategic anxieties of the Great Powers during the “Eastern Question,” turning local events like the Holocaust of Arkadi into international causes célèbres that forced diplomatic intervention. Each uprising, even when militarily defeated, resulted in a political victory, wresting concessions—the Organic Law, the Pact of Halepa, and finally, the autonomous Cretan State—that progressively dismantled Ottoman authority.

The final union in 1913 was the culmination of this centuries-long process. It was achieved when the relentless, century-long struggle of the Cretan people finally coincided with a decisive shift in the regional balance of power brought about by the Balkan Wars. The raising of the Greek flag over Chania was not merely the end of a single conflict but the fulfillment of a historical destiny forged through countless rebellions, a testament to the unconquerable spirit of an island that refused to be subdued.

Related material and sources

Academic Works & Journals

- “Byzantina Symmeikta.” eJournals.

- “Crete and the 1897 War.” In The British and the Turks. Cambridge University Press.

- Peponakis, Manolis G. ΕΞΙΣΛΑΜΙΣΜΟΙ ΚΑΙ ΕΠΑΝΕΚΧΡΙΣΤΙΑΝΙΣΜΟΙ ΣΤΗΝ ΚΡΗΤΗ (1645-1899).

- Prior, David. “‘Crete the Opening Wedge’: International Affairs and American Worldviews during Reconstruction.” Boston University.

- Stavrinos, Miranda. “Palmerston and the Cretan Question, 1839-1841.” Project MUSE.

- “That Greece Might Still Be Free.” OpenEdition Books.

- “The Cretan Insurrection of 1866-69 as reported in the New York Times.” ResearchGate.

- “The geopolitics of the 1821 Greek Revolution.” ResearchGate.

- “The Therisso Uprising.” ResearchGate.

- Tserevelakis, Georgios T. ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ ΤΩΝ ΚΡΗΤΙΚΩΝ ΕΠΑΝΑΣΤΑΣΕΩΝ (Βενετοκρατία-Τουρκοκρατία).

- Tsougarakis, Nickiphoros I. “Prisons and Incarceration in Fourteenth-Century Venetian Crete.” Edge Hill University Research Archive.

Articles & News Sources

- “25 March 1821: The Greek War of Independence.” Marina of Agios Nikolaos.

- “Arkadi Monastery – Crete, Greece.” The Travelin Man.

- “Arkadi Monastery in Rethymno, Greece.” Greeka.

- “ATTEMPTS AT POLITICAL ORGANISATION AND ESTABLISHMENT OF ADMINISTRATIVE STRUCTURES.” Crete 1821 – 2021.

- “Crete’s Role in the Greek Revolution of 1821: A Story of Resistance and Sacrifice.” Rentcars-crete.com.

- “daskalogiannis.” Kretakultur.

- “Eastern Question.” Encyclopædia Britannica.

- “Eleftherios Venizelos.” Foundation of the Hellenic Parliament.

- “FOREIGN POLICY [1833-1897].” Foundation of the Hellenic World.

- “Pact of Halepa.” Encyclopædia Britannica.

- “Revolt Breaks Out in Crete.” Historycentral.

- “Sfakia.” Tourist Guides of Crete.

- “The Cretan Rebellion of 1897 and the Emigration of the Cretan Muslims.” Refugee History.

- “The Great Cretan Revolution Of 1866-1869.” YouTube.

- “The Revolt of St Tito in Fourteenth-Century Venetian Crete: A Reassessment.” Medievalists.net.

- “The revolutionary.” National Research Foundation “Eleftherios K. Venizelos”.

- Various articles from Wikipedia, including: “Kingdom of Candia,” “Lasithi Plateau,” “Sicilian Vespers,” “Sfakians,” “Revolt of Saint Titus,” “Conspiracy of Sifis Vlastos,” “Cretan Muslims,” “Orlov revolt,” “Greek War of Independence,” “Emmanouil Tombazis,” “Cretan revolt (1866–1869),” “Cretan State,” and “Theriso revolt.”

- “War of Independence and Crete.” WW2-Weapons.com.