The harbor of Heraklion is more than just a port; it is a layered storybook of history, where successive empires have written their legacy in stone and water. From its ancient origins to its bustling present, the port has been a stage for pirates, admirals, merchants, and soldiers. Its identity has been shaped by a constant struggle between its immense strategic value and the challenging forces of nature. Today, it lives a double life: a vital hub for modern Greek commerce and travel, and a cherished, living monument to its rich and turbulent past.

Early Origins: From Minoan Seaport to Arab Stronghold

The story of the port begins long before the Venetians. In the Minoan era, this coastline served the great Palace of Knossos, with a harbor located at the modern site of Poros-Katsambas. This ancient port was the gateway for Minoan trade across the Mediterranean. Later, during the Roman period, the historian Strabo noted that a town named “Heraklion” was the seaport for Knossos.

The city and port as we know them today were truly founded around 824 CE by Arab conquerors. They built a fortified city surrounded by a deep defensive trench, or khandaq, giving the city its new name: Rabdh el Khandaq. This name would evolve into “Candia,” the name used for centuries. For the Arabs, the port was not primarily for trade but was a heavily fortified base for pirates raiding Byzantine shipping routes.

When the Byzantine Empire recaptured Crete in 961 CE, they rebuilt the city but left little record of major works on the port itself. It remained a functional but relatively minor harbor, setting the stage for its radical transformation under Venetian rule.

The Venetian Port of Candia: The Jewel of the Realm

When the Republic of Venice took control of Crete in the 13th century, the city, now called Candia, became the capital of their new realm. The port was the heart of Venice’s power on the island—a critical naval base and the main point of export for Cretan goods like wheat, oil, and wine. However, the port was plagued by natural problems, including constant silting and exposure to harsh northern winds. For centuries, Venice poured immense resources into a constant battle against the elements, building and rebuilding the structures that would come to define the harbor.

The Great Guardian: The Rocca a Mare (Koules Fortress)

The most iconic symbol of the Venetian harbor is its massive sea fortress, known to the Venetians as the Rocca a Mare (“Fort on the Sea”) and later nicknamed Koules by the Ottomans.

- Construction and Purpose: Built between 1523 and 1540, it replaced an older, smaller tower that was destroyed by an earthquake. Its primary purpose was to guard the harbor entrance and the entire bay from enemy attack. The foundation was ingeniously created by sinking old ships filled with stones brought from the nearby islands of Dia and Fraskia.

- A Fortress of Two Floors: The fortress is a massive two-story structure covering an area of about 3,600 square meters, with outer walls nearly 9 meters thick in some places to withstand cannon fire.

- The Ground Floor: The dark, vaulted ground floor was a maze of 26 separate rooms. These chambers served as storerooms for food, water, and ammunition, ensuring the fortress could withstand a long siege. Several rooms were also used as grim prison cells, where Cretan rebels were held.

- The Upper Floor: A wide, sloping ramp, built to haul cannons, leads to the upper level. This floor was a self-sufficient military headquarters, containing the living quarters for the fortress commander and his officers, as well as a bakery, a mill, and a small church.

- Defenses and Decoration: The fortress was a formidable weapon. In the 17th century, it was armed with 18 large cannons on the ground floor and another 25 on the rooftop ramparts. As a final touch of Venetian pride, three large marble reliefs of the Winged Lion of St. Mark, the symbol of Venice, were embedded in its outer walls, gazing out to sea.

The Little Koules

For even greater security, the Ottomans later built a smaller, secondary fort known as the Little Koules (Küçük Kale in Turkish). It stood on the opposite side of the harbor entrance, near where the Port Authority building is today. Together, the two fortresses created a deadly chokepoint. The entrance could be sealed off at night with a massive chain stretching between them, making the harbor impenetrable. The Little Koules stood for centuries before it was demolished in 1936 in the name of “modernization”.

The Engine of the Fleet: The Venetian Shipyards (Neoria)

The harbor was not just a fortress but also a major industrial center. Along the waterfront, the Venetians built impressive shipyards, known as the Neoria or arsenals.

- Function: These were the service stations of the Venetian navy. Here, the Republic’s powerful galleys were built, repaired, and stored, especially during the winter months.

- Structure: The Neoria consisted of long, massive stone buildings with high, vaulted roofs. Each arched bay was designed to house a single galley, protecting it from the elements. At their peak, there were three separate complexes of shipyards, totaling 19 bays.

- What Remains: Like the Little Koules, most of the Neoria were demolished in the 20th century to make way for the modern coastal road. Today, only a few of these majestic stone arches survive, standing as silent witnesses to Heraklion’s past as a naval powerhouse.

Supporting Structures: Gates, Warehouses, and Water

The port was a fully integrated complex.

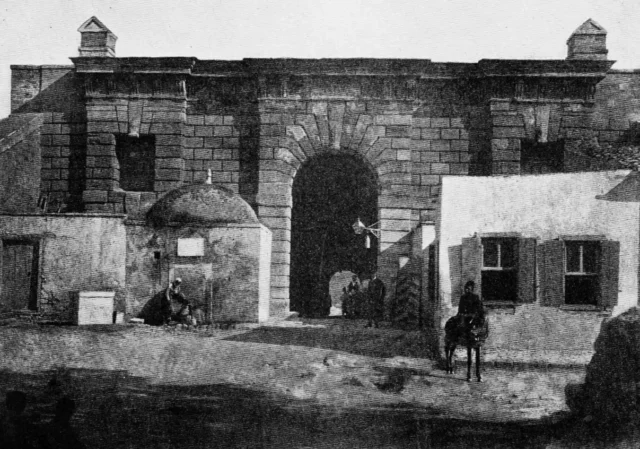

- The Gate of the Mole: To control traffic between the bustling city and the secure port, the Venetians built the Gate of the Mole (Porta del Molo). It stood at the beginning of what is now the pedestrianized 25th of August Street. This gate, too, was torn down during 20th-century modernization efforts.

- Salt Warehouse and Zane Reservoir: Near the shipyards stood other vital buildings. The Salt Warehouse was used to store precious salt, a key commodity in Venetian trade. Nearby, the large Zane Reservoir held thousands of barrels of fresh water to supply the departing ships.

Eras of Change: Ottoman Rule and 20th-Century Demolition

After a grueling 21-year siege, the city fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1669. Under Ottoman rule, the port’s commercial importance declined, as much of the sea trade shifted to Chania. The Ottomans made some repairs and additions, such as adding battlements and a small mosque inside the Koules, but largely maintained the Venetian structures they inherited.

The greatest destruction, however, came not from war but from peace. In the 20th century, a wave of “modernization” swept through Heraklion. Viewing the Venetian and Ottoman structures as relics of foreign occupation rather than part of their own heritage, city planners demolished many historic buildings to make way for modern roads and developments. In this period, the city lost the Little Koules, the Gate of the Mole, and the majority of the magnificent Venetian shipyards.

The Harbor Today: A Living Monument

Today, Heraklion’s harbor is a place of vibrant contrasts. The new, modern port is the third busiest in Greece, serving as a major gateway for ferries, cruise ships, and cargo vessels.

Adjacent to it, the old Venetian basin has been reborn as a picturesque marina for fishing boats and yachts. The historic harbor is now the social heart of the city. The long breakwater extending from the Koules is a favorite promenade for locals and tourists, who come to walk, fish, and enjoy the sea breeze. The waterfront is lined with cafes and tavernas, buzzing with life day and night.

The surviving monuments have been given new life. The Koules fortress has been restored and is now open to the public as a museum and cultural venue, hosting exhibitions and events. The remaining Neoria are also being restored to host cultural activities, ensuring that the echoes of the past continue to resonate in the modern city.

References

- Jacoby, David. “THE OPERATION OF THE CRETAN PORT OF CANDIA IN THE THIRTEENTH AND FIRST HALF OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY: SOURCES, SPECULATIONS AND FACTS.”

- Gratziou, Olga. “Venetian monuments in Crete: a controversial heritage.”

- AllinCrete Travel Guide. “Heraklion Old Venetian Port Harbour.”

- Cretan Beaches. “Koules Fort – Rocca al Mare at Heraklion Port.”

- Cretan Beaches. “Heraklion Venetian shipyards.”

- Cretan Beaches. “Venetian Harbor of Heraklion.”

- GTP Headlines. “Studies Underway to Restore Venetian Port of Heraklio.”

- Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports. “Venetian fortess at the harbour of Heraklion (Koules).”

- Heraklion Municipality. “Heraklion through the centuries.”

- Meet Crete. “Venetian Fortress Rocca a Mare (Koules) – Heraklion.”

- Wikipedia. “Heraklion.”

- Wikipedia. “Koules Fortress.”