The Anatomy of Alienation: Overtourism and the Erosion of Place

Overtourism is not merely a matter of crowds, but a systemic crisis of values that leads to the profound alienation of host communities. By applying this framework directly to the Cretan context, it becomes clear that the visible conflicts are symptoms of a deeper struggle over the very meaning of home and the right to inhabit one’s own world.

The Global Engine of Overtourism: A Crisis of Consumption

Overtourism is a significant challenge to the sustainability of communities and ecosystems globally. It results from a system that values economic returns more than cultural integrity and environmental health. It is defined as a situation where locals or visitors feel that there are too many people and that the quality of life or the visitor experience has declined unacceptably. This definition focuses on the experience of people rather than visitor numbers. Overtourism occurs when a destination’s “carrying capacity”—its ability to handle tourism without major negative effects on its infrastructure, environment, and society—is exceeded. While related to mass tourism, which involves large, organized groups, overtourism specifically refers to the unacceptable decline that happens when a destination can no longer cope with the volume of visitors.

The increase in overtourism results from several connected factors. The growth in global tourist numbers, which passed 1 billion in 2012 and was expected to nearly double by 2030, created more potential visitors. This demand was supported by more affordable travel options, especially the increase in low-cost airlines that made long-distance travel more accessible. This trend is supported by an economic growth mindset in both government and the private sector, which sees tourism as a key tool for economic development. This often leads to a short-term focus on increasing visitor numbers and revenue without enough planning for long-term effects. Technology has helped concentrate this global demand on specific popular destinations. The growth of Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) like Booking.com has given consumers more power but has also increased competition and encouraged higher visitor volumes. The “sharing economy,” with platforms like Airbnb, has added many accommodation options in residential areas. While this is presented as a way for locals to make money, it has had significant negative effects on local housing. It has increased rental prices, lowered the availability of long-term housing, and caused residents to be displaced, a process known as “tourist gentrification.” Social media platforms like Instagram direct large numbers of visitors to the same locations, causing congestion and turning cultural sites into settings for photos.

This economic model creates significant costs for host communities while generating large profits for a small group of stakeholders. Global hotel chains have moved toward business models like franchising. This allows parent companies to grow globally and get consistent revenue while transferring investment costs and local risks to independent owners. The cruise line industry’s model takes more from the local economy. Cruise ships act as self-contained hotels and keep a large portion of visitor spending through their own excursions. They bring thousands of visitors to a location for short periods, which causes severe crowding and puts a strain on local infrastructure. This growth is supported by investment groups and financial institutions that fund large infrastructure projects like airports, cruise terminals, and resorts. This commits destinations to a long-term development strategy based on high numbers of tourists. Government and semi-governmental groups like Destination Marketing Organizations (DMOs) have traditionally defined success by visitor numbers and spending. This creates an institutional preference for promotion instead of management. This group of interests supports the current situation, where the immediate financial benefits of the overtourism economy are given priority over the long-term costs to the local community and environment.

The Right to the City, and Place Alienation

The theories of French philosopher and sociologist Henri Lefebvre help explain the conflicts caused by overtourism. He applied the concept of alienation, traditionally used for industrial labor, to the creation of social space. Lefebvre stated that in modern capitalism, space has become a key commodity. In the same way that private ownership of production separates workers from what they create, the private ownership and commercialization of city land separates residents from their city. Residents help create the social character of a place through their daily lives. However, they find their living space is shaped by real estate markets, government planning, and tourism rather than by their own needs.

Lefebvre’s idea of “The Right to the City” is key to his framework. It is a demand for residents to have control over their urban environment, not just access to its resources. This means prioritizing its function as a community (‘use value’) over its value as a product for tourism and real estate (‘exchange value’). A tourism-focused economy turns the city from a community space into a product for tourists to consume. For residents in many destinations, this results in the ongoing loss of their right to the city.

This general alienation leads to a more specific issue known as ‘place alienation’. Studies in Crete show that it is hard for residents to build community and find meaning when their environment is treated as a product for sale. The connections an individual has to their community are broken, which causes a feeling of separation from one’s own neighborhood. Although the physical space is unchanged, it feels like it belongs to visitors, investors, and markets instead of the residents. This feeling of loss is not just economic but also psychological, causing frustration and anger. Research in Chania, Crete, shows this, with one elderly resident describing a ‘feeling of depression’ from the loss of neighborhood connections and feeling forced out.

Urban and Rural Alienation

Alienation and dispossession are not just urban issues but affect the entire island of Crete. This is caused by economic and political factors across the island. Officially ranked as one of the ten most “overcrowded EU tourism NUTS-2 regions,” Crete has an economy that depends heavily on a single industry. Tourism and related activities make up over 50% of the island’s Gross Domestic Product. This has created an economy dependent on a single industry, where growth is prioritized over social and environmental concerns. The main causes of overtourism, including state policies favoring capital investment, the global financial influence on real estate, and a focus on tourism, affect both urban and rural areas. While alienation appears in different forms, the basic process of losing control and property is the same.

A Tale of Two Crises: Housing and Commons

A comparison shows that key signs of alienation are similar in urban and rural areas. The housing crisis is a clear symptom of overtourism in both settings.

- In Urban Chania, the “Airbnb trend” has led to a major decrease in available long-term rentals because landlords can make more money from tourists. This has created a severe housing shortage for students, seasonal workers, and low-income residents. This crisis is also seen in rural and coastal communities across Crete, where essential workers like doctors and teachers cannot find affordable year-round housing in the areas where they work. 🏘️

- In Rural Crete, Cretans from cities and foreign investors are renovating old family homes in villages to rent to tourists on platforms like Airbnb. This turns heritage into commercial products, weakening village communities and reducing the housing available to locals.

The system’s lack of resilience is shown by the migrant crisis. An increase in arrivals has strained the island’s housing and social services, which are set up for tourism, not community needs. This has increased competition for housing.

The takeover of common areas is another parallel.

- In cities, public spaces are commercialized. For example, community benches were removed from Splantzia Square in Chania after complaints from tourist shop owners, removing access for a vulnerable group to favor businesses. Sidewalks and squares are often taken over by commercial tables and chairs, turning public areas into private commercial zones.

- In rural areas, the common areas are the natural landscapes. The “beach towel movement” in Crete and other Greek islands is the rural equivalent of this urban issue. Protesters oppose the illegal expansion of businesses onto public beaches, which by law are public goods. This action effectively makes the coastline private and blocks free access. The local effort to stop a large hotel from being built on the protected Falasarna beach was described as a defense of “natural commons” from corporate takeover, showing the same type of resistance.

The Erosion of Identity

Finally, the loss of community and identity is similar in both areas.

In Chania, residents describe the “disneyfication” of the historic center, where the city’s character is replaced by a generic landscape for tourists. This causes a significant loss of identity and a feeling of being disconnected from their history.

This is similar to the “heritagization” of rural culture, where tradition is simplified and marketed for tourists. This can lead to an “erasure of evidence on hardship and oppression” when a historic home is changed into a rental property without its original context. As the year-round population in villages decreases, the social life of the village is replaced by interactions with tourists. This leads to seasonal alienation, where locals feel like “strangers in my own village.” These similar struggles show a shared experience of alienation across the island.

The Devaluation of Heritage: A Tale of Two State Decisions

The Greek government’s recent actions are not isolated policy choices but reflect a coherent, systemic worldview that subordinates the intrinsic and common value of cultural heritage to the logic of commercialization and strategic development. The verdict on Papoura Hill and the new national ticketing policy for archaeological sites serve as two powerful case studies, revealing a consistent ideological stance where heritage is viewed through an instrumental lens—either as a commodity to be monetized or as an obstacle to be sacrificed.

Case Study: The Papoura Hill “Monument-Sandwich”

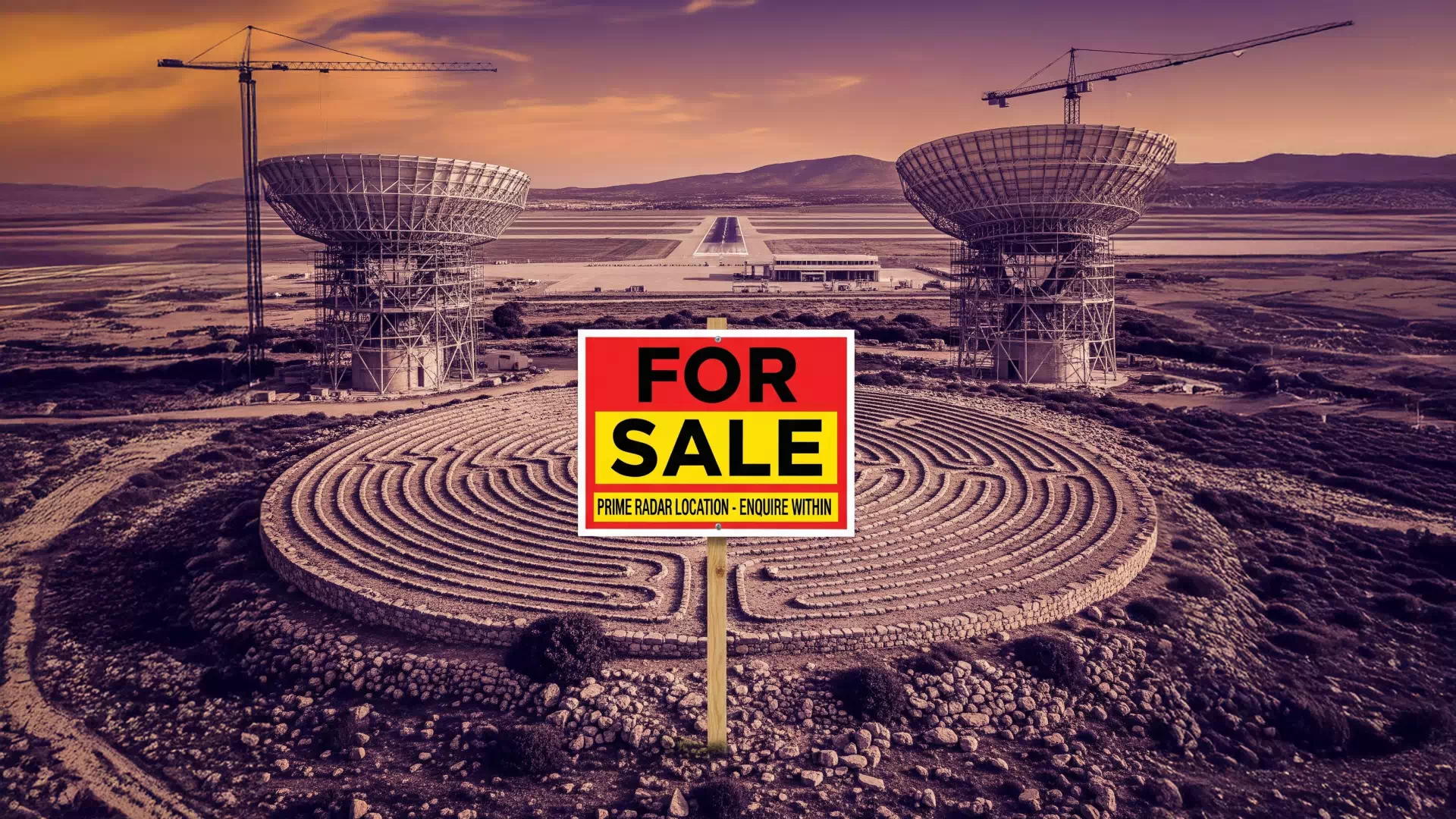

The situation at Papoura Hill in Crete highlights a direct clash between protecting priceless heritage and pushing forward a major development project backed by powerful interests.

A Clash of Values

On one side, you have a recently discovered, one-of-a-kind Minoan monument.

- Significance: Dated to 2000-1700 BCE, the 48-meter-wide circular structure is unique in Minoan archaeology—a true unicum. Its scale suggests it was a major ceremonial center for a large community. Experts believe that after study, it could qualify as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

On the other side is the new Kasteli International Airport.

- Significance: It’s one of Greece’s largest public works, designed to handle 18 million passengers. Critically, it’s being built next to a military airbase and its powerful radar will serve a dual military function, boosting Crete’s strategic importance for NATO. This gives the project a “national importance” status that tends to override other concerns.

The Controversial Decision

Just last month, on July 10, 2025, Greece’s Central Archaeological Council (KAS) voted 16-1 to approve the installation of the airport’s radar facilities right next to the monument.

The plan involves placing two large radar installations just 20-30 meters from the ancient structure, effectively creating a “monument-sandwich.” Critics argue the required construction will permanently damage the monument and its surrounding landscape.

Opponents, including the Association of Greek Archaeologists (SEA), claim the decision was deeply flawed and politically motivated.

- Flawed Process: The KAS meeting was described as a “tribunal” where archaeologists who protected the site were pressured to accept the plan.

- No Site Visit: Critically, the council refused to conduct an on-site inspection, a standard practice for such complex cases. This suggests the decision may have been made without a proper assessment.

- Illegal Procedure: Greek law requires that multiple alternative solutions be evaluated for major projects. However, KAS was presented with this as the “only technical solution,” which constitutes a serious procedural flaw.

- Political Interference: The outcome is widely seen as a “premeditated decision” to approve a political mandate. The Minister of Culture, Lina Mendoni, had made public statements supporting the outcome before the council even met, undermining its independence.7 To justify the radar’s placement, the Minister even proposed a speculative theory that the monument was an ancient beacon (phryctoria), creating a false historical link to the modern radar. Archaeologists have widely dismissed this claim as a cynical attempt to provide political cover.

Case Study: The 2025 Ticketing Policy Overhaul

The second case study, a significant overhaul of the ticketing policy for Greece’s 350 state-managed archaeological sites and museums effective April 1, 2025, further illuminates the government’s instrumental view of heritage.

From Public Good to Priced Commodity

The new policy replaced a complex nine-level system with a simplified five-tiered pricing structure, based primarily on annual visitor numbers. The most prominent change was a 50% increase in the standard admission fee for the Acropolis of Athens, which rose from €20 to a flat €30 year-round. Other major sites saw even more dramatic increases. The ticket for the Palace of Knossos in Crete rose from €15 to €20, while sites like the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens and the Archaeological Site of Mycenae saw their prices jump from €12 to €20.

However, the most significant structural change, with the greatest impact on accessibility for residents and budget-conscious travelers, was the abolition of two long-standing value-oriented policies. First, the 50% discount on admission fees during the winter low season (November 1 to March 31) was eliminated, establishing a single, high-season price year-round. This means that while the summer price for Knossos increased by 33.3%, the winter price increased by 150% (from €8 to €20). The winter price for the Temple of Olympian Zeus increased by a staggering 400% (from €4 to €20). Second, most multi-site combination tickets, such as the popular €30 Athens combo ticket that granted access to seven sites over five days, were abolished. Visiting those same seven sites now requires purchasing individual tickets that could total over €90, representing a massive effective price increase for visitors wishing to engage deeply with the city’s heritage.

The following table:

Site/Museum Name | Previous Price (Summer / Winter) | New Year-Round Price (April 2025) | % Increase (vs. Summer) | % Increase (vs. Winter) |

Acropolis of Athens | €20 / €10 | €30 | 50% | 200% |

Palace of Knossos (Crete) | €15 / €8 | €20 | 33.3% | 150% |

Temple of Olympian Zeus (Athens) | €8 / €4 | €20 | 150% | 400% |

Archaeological Site of Mycenae | €12 / €6 | €20 | 66.7% | 233.3% |

Athens Combo Ticket | €30 (7 sites, 5 days) | Abolished (Cumulative cost > €90) | N/A | >200% |

Analyzing the Impact on Access and the Principle of Common Heritage

The official justifications provided by the Greek Ministry of Culture centered on aligning ticket prices with the “European average” and generating necessary revenue for the preservation and maintenance of sites amidst surging post-pandemic tourism. While international tourists may absorb these costs, significant concerns have been voiced domestically. Archaeologists, heritage sector unions, and political opposition parties have criticized the scale of the increases and the abolition of affordable options, viewing the policy as a move towards the aggressive commercialization of cultural heritage. The policy disproportionately impacts Greek citizens, residents, and budget-conscious travelers, particularly those who took advantage of winter discounts and combo passes to access their own national patrimony. The changes signal a clear prioritization of revenue extraction from high-paying, short-term foreign tourists over the principle of ensuring broad and affordable access for the domestic population, effectively treating heritage less as a public good and more as a premium consumer product.

What State Policy Reveals About the View on Communities and Heritage

When viewed together, the Papoura verdict and the 2025 ticketing policy are not contradictory or isolated events. They are two sides of the same coin, revealing a consistent and coherent ideological stance from the Greek state. In this worldview, cultural heritage is not valued for its intrinsic, scientific, or communal worth, but is judged by its utility within a market-driven and geostrategic framework.

In the case of Papoura, the monument’s unique heritage value became an “obstacle” to a project of perceived higher strategic and economic importance; therefore, it was sacrificed. In the case of the ticketing policy, the heritage of the Acropolis and other sites is seen as an under-leveraged asset, whose primary function is to generate maximum revenue; therefore, its price was increased, and access for less-affluent groups was curtailed. In both scenarios, the local and national community is alienated and disenfranchised. In Papoura, the community’s desire to protect its local heritage is overridden by state and corporate power. With the ticketing policy, the national community’s ability to affordably access its own shared history is diminished in favor of a commercial logic. The state, in these instances, positions itself not as the steward of the commons, but as the primary agent of its enclosure, commodification, and, when deemed necessary, its destruction.This approach risks a “boomerang effect.” The very development the Kasteli airport is meant to serve—mass tourism—is built upon Greece’s global brand as a cradle of civilization and a responsible custodian of world heritage. The international outrage sparked by the Papoura decision, with hundreds of academics protesting and global media reporting on the controversy, places this brand under intense scrutiny. This negative attention could have damaged the then-pending UNESCO nomination for the Minoan Palaces, a serial nomination for which the Papoura find is a critical new element. By prioritizing the airport’s construction over the monument’s protection, the government engaged in a form of self-sabotage, risking the international reputation that underpins the long-term health of its tourism economy.

Resistance and the Fight for Public Access and Resources

The increasing pressure of overtourism and the perceived lack of state intervention have been met with resistance. Across Crete, various movements have emerged. These are not isolated protests but represent an island-wide effort by communities to reclaim public spaces, assert their right to their locality, and demand a more sustainable future.

Reclaiming the City and the Coast: From Urban Activism to the “Beach Towel Movement”

The city of Chania is a center for this resistance. It is one of the few places in Greece where overtourism has led to social movement campaigns by the local population. Public dissatisfaction is visible in graffiti that protests tourism growth. Grassroots organizations, such as the “Initiative Against Touristification,” have organized campaigns to highlight the negative effects on housing and community life. Student and teacher associations have held public protests, demanding policy interventions to address the housing crisis that directly affects their members. These actions are part of the struggle for the “right to the city.” Residents are fighting against the negative social effects caused by an economy focused only on tourism.

This urban activism is mirrored in rural and coastal areas by the “beach towel movement.” This grassroots movement began on the island of Paros and spread to Crete and other islands. It is a direct response to commercial businesses illegally using public coastlines. According to Greek law, beaches are public. However, local people have protested against hotels, bars, and restaurants placing umbrellas and sunbeds outside of their licensed areas. This practice limits public access and privatizes parts of the shoreline. The movement is presented as a response to “lawlessness” and the state’s failure to act. Its goal is to ensure beaches remain free for everyone. This action asserts a collective right to a natural public resource. It is similar to the urban effort to reclaim public squares from commercial use.

A United Front: The Scientific, Social, and Political Coalition to Save Papoura

The KAS decision on Papoura Hill caused an immediate and unified reaction. A multi-sector coalition formed, turning a local planning dispute into a national and international issue.

The scientific community in Greece and abroad was central to the opposition. This provided the movement with scientific and academic support. The Association of Greek Archaeologists (SEA) and the Association of Contract Archaeologists (SEKA) issued strong announcements, calling the decision a “day of shame.” The protest became international after a letter gathered over 300 signatures from Cretologists and field archaeologists worldwide. This showed a global scientific consensus against the Greek government’s plan and made the case an issue of international heritage concern.

In addition to the scientific response, the local community also mobilized. The Municipality of Minoa Pediada and its Mayor, Vasilis Kegeroglou, have consistently opposed the decision. They provide the official local government opposition and have the legal standing to challenge the decision in court. A “Citizens’ Committee for the Protection of Papoura” was formed to organize protests, and an online petition on Avaaz.org quickly gathered thousands of signatures, demonstrating widespread popular opposition. The coalition was also supported by the Technical Chamber of Crete, which represents the island’s engineers. Their opposition provided technical credibility and countered the government’s claim that the opposition was an “anti-development” stance by “romantic” archaeologists.

This coalition has stated its intention to use all available legal and political methods. The primary legal action is a “Writ of Annulment” before the Council of State, Greece’s highest administrative court. The appeal is expected to be based on strong grounds, including the violation of the constitutional duty to protect heritage (Article 24), the failure to follow legally required procedures (such as studying alternative solutions), and a lack of sufficient legal reasoning for the decision. In parallel, opponents plan to appeal to international bodies like UNESCO and Europa Nostra, seeking to place Greece’s heritage management under global review and potentially list Papoura as an endangered site.

Emerging Alternatives: The Discussion of Degrowth and Regenerative Tourism

Beyond specific protests, a broader critique of the current development model is emerging in Crete. This has led to alternative proposals for the future. The discussion by academics and activists about “tourism degrowth” challenges the current situation. This viewpoint rejects the “current model of continuous and unlimited growth of tourism.” It promotes an alternative model based on “locality, development of small-scale enterprises, quality of life, environmental sustainability,” and the rights of local communities. This is a challenge for an economy that depends heavily on tourism. However, the degrowth debate shows a growing recognition that the current approach is not sustainable.

These ideas are complemented by practical, local initiatives that suggest a more sustainable future. Across the island, some businesses and organizations are starting to use regenerative practices. Some hotels are working to reduce their environmental impact by sourcing food locally and using conservation systems. Tour operators are developing low-impact products that support small, family-run accommodations, distributing economic benefits more widely. One example is the “TUI Field to Fork Greece” initiative. It follows the principles of regenerative tourism by seeking to improve the local ecosystem and community. The initiative connects local farmers with hotels and supports regenerative agricultural practices. These practices improve soil health and help the local economy, which benefits farmers, businesses, visitors, and the environment.

The different forms of resistance in Crete should not be seen as contradictory. They range from the passive “feeling of depression” of a resident, to policy proposals from those who want to improve the system, to graffiti from activists who reject the system. Instead, these are all responses to the same underlying social conditions, shaped by each person’s social position, resources, and ability to act. The Papoura case, in particular, shows how a local land-use dispute can be successfully internationalized. Through the use of global academic networks and the media, the conflict changed from a local planning issue into a global discussion on Greece’s national heritage policy. This created significant external pressure on the government.

Creating a New Model for Heritage and Tourism

The alienation of local populations and the damage to their cultural and natural heritage are direct consequences of a development model that prioritizes short-term monetary benefits over the long-term values of community, culture, and environmental health. A more sustainable future requires more than minor adjustments; it requires a shift from a model of exploitation to one of stewardship.

A Failure of Valuation and Governance

The alienation of locals and the degradation of heritage in Crete result from a system that is biased against non-monetary values. Traditional economic analysis, with its focus on market transactions, does not properly account for the full value of cultural and environmental resources, many of which are public resources without a set price. This leads to a “market failure,” where the real costs of tourism, like environmental damage or social harm, are not paid by the developers or tourists who cause them. Standard economic impact assessments, which focus on metrics like GDP contribution and job creation, capture the tangible benefits while ignoring these intangible costs, creating an incomplete picture for decision-makers.

The case studies of Chania, the Papoura decision, and the 2025 ticketing policy show a consistent pattern of this failure. In each case, a decision-making process focused on monetary value—whether from real estate, development, or revenue—has overridden the value of the place and its heritage for the community. To counter this, a broader economic framework is needed to recognize and quantify the value of these assets. Non-market valuation offers tools for this. The Total Economic Value (TEV) framework provides a structure for identifying all the benefits an asset provides, including its direct use value, indirect use (like ecosystem services), and its option, bequest, and existence values. Methods such as the Contingent Valuation Method (CVM), which uses surveys to determine the public’s “Willingness-to-Pay” (WTP) for preservation, and the Travel Cost Method (TCM) can translate these non-monetary values into policy terms. These tools, while not perfect, are important for making the non-monetary value of heritage clear in economic and political decisions. This allows for a more balanced accounting of the costs and benefits of tourism.

Strategic Recommendations

Putting these principles into action requires a new approach to tourism policy and governance. The goal of tourism development must be redefined. Instead of the goal of maximizing visitor numbers, the objective must be optimizing resident well-being, environmental health, and visitor experience. Achieving this requires a multi-part approach that integrates the valuation of non-monetary assets into decision-making and empowers communities. The following recommendations outline a path toward this new model:

- Integrate Non-Market Valuation into Policy: Government and planning authorities should require the use of non-market valuation techniques, such as the TEV framework and WTP studies, in all major tourism-related policy and project assessments. This will make the environmental and social costs of development visible and allow for a more complete cost-benefit analysis, countering the bias toward monetary benefits.

- Empower Local Governance: Tourism planning decisions should be made at a more local level. This includes creating formal roles for local communities through participatory planning, community advisory boards, and support for community-based tourism businesses. Giving residents control over tourism in their area is the most effective way to ensure it aligns with their values and needs.

- Reform DMOs and Redefine Success: The goals and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for Destination Marketing Organizations must be reformed. Success should no longer be measured primarily by visitor numbers or total tourist spending. New metrics must be adopted that reflect a more complete vision, including a Resident Quality of Life Index, indicators of ecosystem health (e.g., water quality), visitor satisfaction scores, and the health of local businesses not dependent on tourism.

- Implement an Island-Wide Land Use and Housing Policy: There should be consistent, island-wide regulations for short-term rentals, including limits on the number of days a property can be rented and the number of licenses per district. Create affordable housing programs, funded by fees on new tourism developments, to address the housing crisis affecting residents.

- Legally Protect Public Resources: Enforce existing laws and create new ones to protect the public’s right of free access to all coastlines, beaches, and natural landscapes. This must include strict penalties for commercial businesses that illegally use public space, directly addressing the core issue of the “beach towel movement” and legally protecting public resources.

- Foster a Regenerative Economy: Support the shift from an economy based only on tourism to a more diverse one. This involves redirecting support towards small-scale, regenerative agriculture and creating local supply chains that connect these producers with the hospitality sector, ensuring tourism money stays in the local community.

The choice facing destinations like Crete is between two competing models, as shown in the table below.

Mass Tourism / Exploitation Model | Sustainable / Stewardship Model | |

Primary Goal | Maximize visitor numbers and gross revenue. | Optimize community well-being and ecosystem health. |

Economic Logic | Short-term profit; high economic leakage; externalization of social/environmental costs. | Long-term value; local circular economy; internalization of costs through taxes/fees. |

Cultural Approach | Commodification; staged authenticity; culture as a product. | Co-creation; lived heritage; culture as a source of identity and exchange. |

Environmental Approach | Resource extraction; high footprint; exceeding carrying capacity. | Conservation and regeneration; low footprint; operating within carrying capacity. |

Governance Model | Top-down; driven by external corporate and national bodies (DMOs). | Bottom-up; community-led or co-managed; DMOs as destination managers. |

Primary Metric | Tourist arrivals; total tourist expenditure; GDP contribution. | Resident Quality of Life Index; Ecosystem Health Index; visitor satisfaction. |

The global overtourism crisis and its effects—such as cultural commodification, environmental damage, and the alienation of local communities—are the result of a system that treats places as products for consumption. The conflict is not between residents and tourists, but between two different value systems: one that views a place as a resource for exploitation and another that views it as a home. The path forward requires a major shift in thinking, starting with an effort to recognize, value, and protect the non-monetary qualities of a place. The resistance from Chania to Papoura and the emergence of alternative models show that a new vision for tourism is possible. The goal is to move from a model that sells a product to one that manages a place. This would ensure travel is a positive exchange for both visitors and residents, securing the future of global heritage.