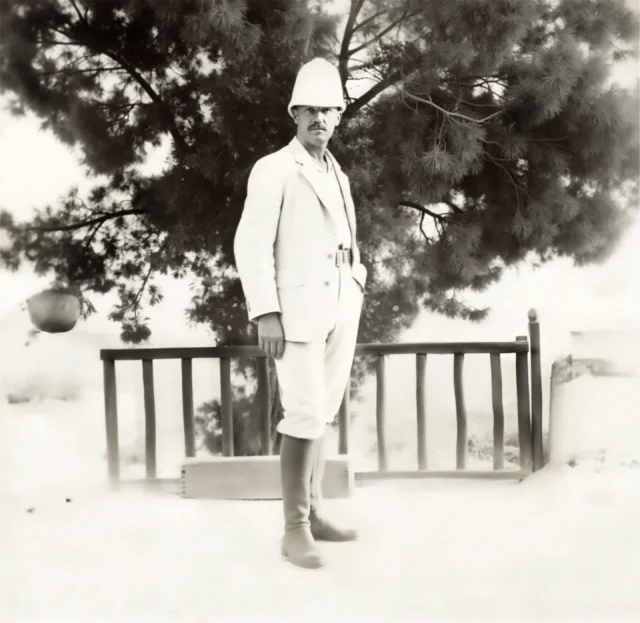

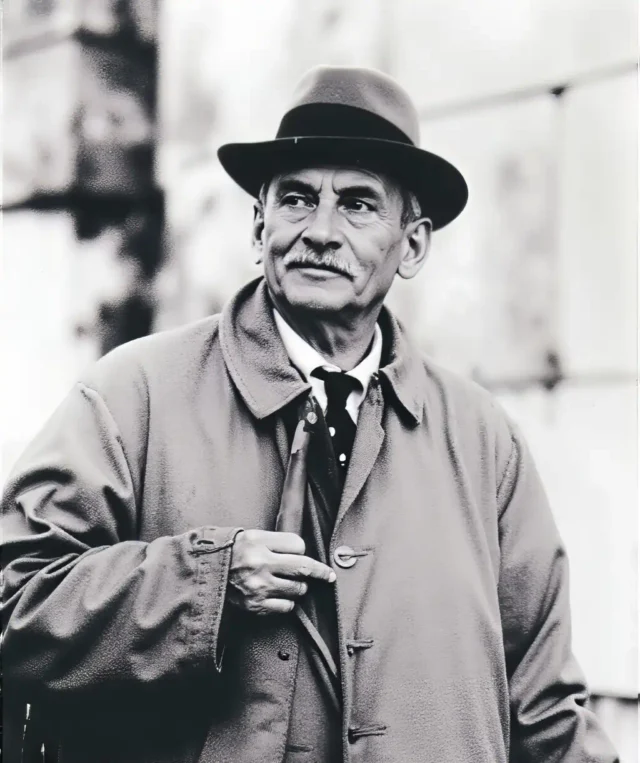

Federico Halbherr excavating the northeast compex at Phaistos. The photo is facing east where the road to Heraklion is barely visible and the area that today is characterized by the bustling town of Moires appears remarkably undeveloped.

Unearthing Minoan Crete – The Pioneering Era (Late 19th Century – 1940s)

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a significant period in understanding Crete’s ancient history. For centuries, knowledge of the island’s past came primarily from Classical texts and mythology, with physical remains largely unexamined or misinterpreted. However, political change, increasing scholarly interest, and the work of early archaeologists led to the discovery of the Bronze Age civilization now known as Minoan. This report describes the individuals and institutions that led archaeological work in Crete from the late 19th century until the Second World War in the 1940s.

The political situation in Crete during this period was important. Under Ottoman rule for centuries, large-scale archaeological work by outsiders was often difficult. Early attempts, like that of Minos Kalokairinos at Knossos in 1877-78, were sometimes stopped by Ottoman authorities. A significant change occurred with the establishment of the autonomous Cretan State (1898-1913), under the protection of Great Britain, France, Italy, and Russia. This stability and European influence allowed more foreign archaeological missions. The desire of these major powers to exert cultural and political influence likely contributed to supporting their national schools’ activities on the island. This political change provided access to major sites like Knossos, Phaistos, Gournia, and Malia, allowing for sustained and systematic investigation by newly established or increasingly active foreign archaeological schools. Furthermore, the autonomous status helped ensure that many significant discoveries remained on the island, forming the basis of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum’s collection. Before this, isolated discoveries had been made, and individuals like the British naval captain Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt had surveyed the island in the mid-19th century, correctly identifying the location of ancient Phaistos using topography and textual references.

The initial motivation for much of the archaeological interest came from the study of Classical Greece and the desire to find physical connections to ancient texts and myths. Epigraphy was a significant factor; Federico Halbherr, an important Italian figure, became known for his work on the Gortyn Law Code, and Arthur Evans went to Crete in 1894 seeking evidence for early writing systems, particularly seal stones he believed contained evidence of a pre-alphabetic script. However, excavations soon revealed something much older and different. The discovery of large, complex structures such as the palaces at Knossos and Phaistos, along with their distinct material culture (pottery, frescoes, artifacts), significantly changed the focus. Archaeologists realized they were uncovering not just a forerunner to Classical Greece, but a sophisticated Bronze Age civilization. This change from textual research to discoveries from excavations shows how fieldwork can alter historical understanding.

Various individuals were involved in the exploration of Crete during this early phase. Early Cretan scholars and antiquarians, associated with local groups like the Philological Association of Heraklion, played important roles as both excavators and facilitators. At the same time, foreign archaeological missions from Italy, Great Britain, the United States, and France established themselves on the island, often defining distinct geographical areas of focus. Their work, with that of independent researchers, formed the basis for modern Cretan archaeology. This report will examine the contributions of these key individuals and institutions, detailing their activities and discoveries up to the 1940s, which marks the end of this initial period of exploration before the major post-war expansion of archaeological research.

Early Cretan Archaeologists and the Greek Archaeological Service

Although foreign missions were prominent, the work of Cretan archaeologists and the developing Greek Archaeological Service was essential for the advancement of archaeology on the island. These individuals were excavators and also key facilitators, administrators, and institution builders who managed the complex political and cultural conditions of early 20th-century Crete.

Minos A. Kalokairinos (Μίνως Α. Καλοκαιρινός) stands as a crucial forerunner. An antiquarian from Heraklion, he conducted the very first, albeit limited, excavations at the site of Knossos in 1877-1878. He unearthed large storage jars (pithoi) in the west wing area, demonstrating the site’s potential. Although his work was cut short after only three weeks by Ottoman authorities wary of finds leaving the island, Kalokairinos’s initiative revealed the importance of the Kephala hill and undoubtedly influenced later excavators, including Arthur Evans. His effort represents the earliest local attempt at systematic exploration of a major Minoan center.

Iosif Hatzidakis (Ιωσήφ Χατζιδάκης) (1848-1936) was a leading figure in Cretan archaeology during this time. As President of the Philological Association (Syllogos) of Heraklion, he was an important local contact and facilitator for foreign missions and corresponded with individuals such as Federico Halbherr. He conducted significant excavations himself, including at the Idaion Antron (a sacred cave on Mt. Ida, initially with Halbherr), the harbour site of Amnisos, and the major Greco-Roman city of Gortyna. He also performed important early work at Tylissos, discovering Minoan villas (likely around 1909-1913, before Xanthoudides‘ later work there). Notably, Hatzidakis and Stephanos Xanthoudides played a key role in founding the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. This museum started as a small collection in 1883, and its first dedicated building was constructed between 1904 and 1912. This was essential for keeping Cretan antiquities on the island for housing and study. Hatzidakis also served as the first Ephor of Antiquities for Crete, providing official supervision. In this role, he carried out initial investigations at Malia between 1919 and 1922, concentrating on the Chrysolakkos ossuary structure, before the French School began the main site excavations. He also conducted early explorations at Dreros. Hatzidakis’s career demonstrates the mutually beneficial relationship between local knowledge and foreign resources; his position and expertise were very valuable to visiting archaeologists, and his own work and efforts in institution-building established an important foundation for archaeology in Crete.

Stephanos Xanthoudides (Στέφανος Ξανθουδίδης) (1864-1928) worked closely with Hatzidakis, especially in establishing the Heraklion Museum. His archaeological work focused significantly on the early periods of Minoan civilization and funerary practices. Between 1904 and 1906, he excavated an important Prepalatial cemetery complex at Koumasa in the Asterousia Mountains of southern Crete, uncovering characteristic circular tholos tombs, associated rectangular structures, and rich grave goods. This work provided crucial insights into Early Minoan society and burial customs. He also excavated at the Minoan villas of Tylisos, with work recorded for 1923-1925, following Hatzidakis’s initial exploration there. In 1917, Xanthoudides conducted the first excavations at the important Geometric/Archaic site of Dreros. His contributions were vital in broadening the understanding of Cretan archaeology beyond the palatial centers to include the island’s earlier prehistory and later Iron Age.

The next generation of Greek archaeologists began their careers in the interwar period, building upon the foundations laid by Hatzidakis and Xanthoudides. Spyridon Marinatos (Σπυρίδων Μαρινάτος) (1901-1974), who later became known for his work at Akrotiri on Thera, conducted significant early excavations in Crete before 1940. His work focused notably on cult sites: he excavated a Late Minoan III shrine with distinctive “snake tube” cult vessels at Gazi, explored sites near Kousses, and investigated the important Arkalochori Cave, known for its rich deposits of bronze weapons and votive offerings, including double axes (partly in cooperation with Nikolaos Platon). In 1935, he excavated the important early Temple of Apollo Delphinios at Dreros, uncovering hammered bronze statuettes (sphyrelata) of the Apollo triad. Marinatos’s early focus on ritual sites and caves expanded the scope of Minoan studies.

Nikolaos Platon (Νικόλαος Πλάτων) (1909-1992), known for his post-war discovery of the palace at Zakros, also performed important work before 1940. He collaborated with Marinatos at the Arkalochori Cave and conducted excavations at Poros-Katsampas, the harbour town of Knossos, between 1930-1935 and 1938-1941. This work revealed details about Knossos’s maritime connections and the characteristics of Minoan port settlements. His early career demonstrates a focus on specific site types that complemented the ongoing work at the major palaces.

The Greek Archaeological Service, officially established in the 19th century, strengthened its systematic activities in Crete through the appointment of Ephors such as Hatzidakis and the work of archaeologists including Xanthoudides, Marinatos, Platon, and Vasileios Theofaneidis (Βασίλειος Θεοφανείδης) who was active as Ephor in Western Crete between 1935 and 1941. Its responsibilities included conducting independent excavations, issuing permits and supervising the work of foreign missions, preventing illegal trade in antiquities, and importantly, establishing and managing the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. The Ephorates (regional divisions, for example, the 23rd Ephorate covering Heraklion or the Lassithi Ephorate) became the main administrative bodies for managing the island’s growing archaeological heritage. The work of these Greek early figures shows an increasing local ability for archaeological research and heritage management, working alongside, and sometimes in cooperation with, the major foreign expeditions. Their focus often supplemented that of the foreign schools by exploring different types of sites or periods, and ensuring a Cretan perspective in the interpretation of the island’s history.

The Foreign Missions: Unveiling Crete’s Past

In addition to the significant work of Cretan archaeologists, the early 20th century saw the arrival and significant activity of several foreign archaeological missions. Supported by institutions and funding from their home countries, these missions brought considerable resources and personnel to the island, conducting large-scale excavations that significantly altered the understanding of Aegean prehistory. Each mission typically developed specific geographical or thematic focuses, providing distinct information for the overall understanding of ancient Crete.

The Italian Archaeological Mission (Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene – SAIA): The Mesara Plain and Beyond

The Italian presence in Cretan archaeology was arguably the earliest and most sustained of the foreign missions, primarily due to the dedicated work of its central figure, Federico Halbherr (1857-1930). An epigrapher by training, Halbherr began explorations in Crete as early as 1884. His discovery and publication of the Great Law Code of Gortyn in 1884 brought him international recognition and strengthened his connection to the island. In the same year, he conducted initial investigations at Phaistos and, with Iosif Hatzidakis, explored the Idaion Antron. Halbherr’s work defined the Italian focus on the fertile Messara plain in south-central Crete. He formally established the Italian Archaeological Mission in Crete around 1899 (though 1898 has also been suggested), which later became integrated with the Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene (SAIA), founded in 1909. Halbherr directed the major excavations at Phaistos from 1900 to 1904, alongside his student Luigi Pernier. Simultaneously, he initiated and oversaw the extensive excavations at the nearby site of Hagia Triada, which continued intermittently from 1902 until 1914, involving a team of Italian archaeologists. He also explored the site of Afratì (ancient Arkades) in 1894 and continued work at Gortyna. Halbherr maintained extensive correspondence with other key figures like Arthur Evans and relied on local collaborators such as Manoli Iliakis. His long career and focused efforts established a dominant Italian archaeological presence in the Mesara.

Luigi Pernier (1874-1937) was Halbherr‘s principal collaborator and successor. He co-directed the Phaistos excavations (1900-1904) and continued work there until 1908. His most famous discovery was the enigmatic Phaistos Disk in 1908, found in a basement room of the palace. He also worked extensively with Halbherr at Hagia Triada (1902-1908) and participated in excavations at Gortyna and the sanctuary site of Lebena (modern Lentas) between 1900 and 1913.

Several other Italian archaeologists made significant contributions as part of the Mission and later the School. Antonio Taramelli (1868-1939) conducted early work at Phaistos in 1894, excavating pottery at Halbherr’s request. He also explored prehistoric caves, finding Neolithic remains at Miamou (1894) and excavating the Kamares Cave (1899), known for its distinctive Middle Minoan pottery style. Later, he initiated excavations at the site of Apollonia (modern Agia Pelagia) on the north coast, though the exact dates are unclear. Roberto Paribeni (1876-1956) and Enrico Stefani (1869-1955) were key members of the Hagia Triada excavation team during the main campaigns between 1902 and 1914. Luigi Savignoni (1864-1918), along with Gaetano De Sanctis, explored western Crete in 1893, identifying mainly Classical and later sites. He also published early finds, including relief pithos fragments recovered by Halbherr. Lucio Mariani (1865-1924) spent three months in Crete in 1893 collaborating with Halbherr, conducting explorations and notably conducting the first analysis of Kamares ware pottery. He returned in 1896, visiting Knossos and other sites, and published observations on relief pithoi. Gaetano De Sanctis (1870-1957), besides his early work in the west with Savignoni, explored Afratì (Arkades) in 1908 and participated in the later Hagia Triada campaigns (1910-1914). Giuseppe Gerola (1877-1938), primarily known for his extensive documentation of Venetian monuments in Crete (1900-1902), also participated briefly in the archaeological research at Gortyn around 1900. Antonio Minto (1880-1954) focused on the area around Phaistos, excavating fortification walls on the nearby hill of Christos Effendi between 1909 and 1922.

Later in this period, Doro Levi (1899-1991) conducted extensive excavations at Afratì (Arkades) in 1924, discovering a significant Geometric-Archaic settlement and necropolis. His publication on the Early Hellenic pottery from this site was influential. While his major work at Phaistos began in 1950, his 1924 excavations established his early involvement in Cretan archaeology.

The sustained Italian activity, particularly in the Messara, shows clear continuity of personnel and focus. Halbherr’s initial successes led to decades of research concentrated on Phaistos, Hagia Triada, and Gortyn. This regional concentration of work strongly influenced early interpretations of Minoan civilization, which were largely based on evidence from south-central Crete. The succession from Halbherr to Pernier, and the later involvement of Levi at sites previously explored by the mission, indicates a strong institutional commitment and knowledge transfer within the Italian archaeological community working on the island.

The British School at Athens (BSA): Knossos, East Crete, and Cave Sanctuaries

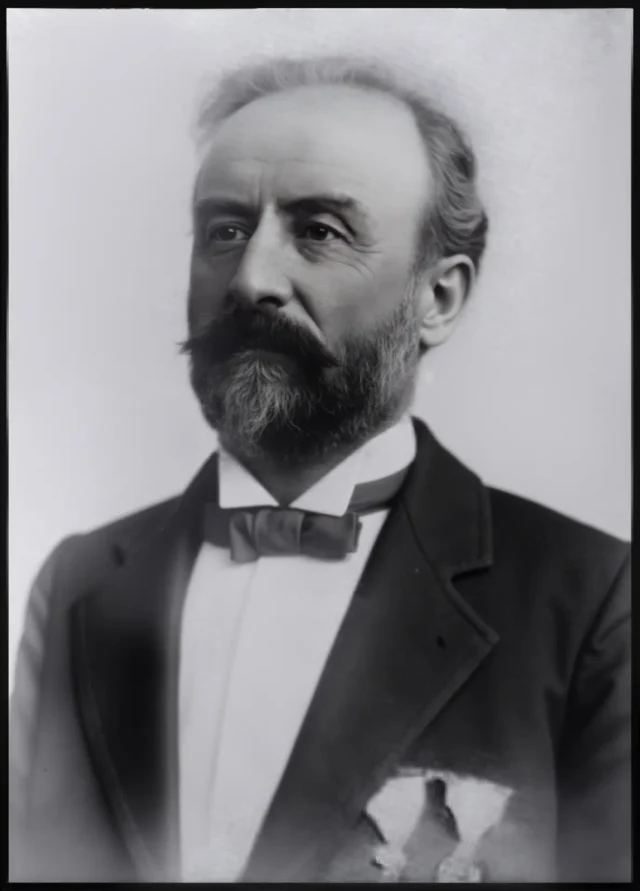

The British engagement with Cretan archaeology in this period is closely linked with Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941) and his extensive excavations at Knossos. Drawn to Crete in 1894 by his interest in early scripts, Evans acquired the Knossos site and began large-scale excavations in March 1900. His work, continuing with interruptions until 1931, uncovered the vast palace complex and led him to define the Minoan civilization, establishing its chronological framework (Early, Middle, Late Minoan periods) and identifying the Linear A and Linear B scripts. Evans’s discoveries received worldwide attention and fundamentally changed the understanding of European prehistory. Beyond Knossos, Evans also showed interest in other sites, purchasing artifacts from the Psychro Cave in 1894, visiting it in 1895, and conducting a small test excavation there in 1896. He also visited Lato, initially misidentifying its ruins as prehistoric, and Zakros in 1894 and 1896.

Essential to the success and interpretation of the Knossos excavations was Duncan Mackenzie (1861-1934), a Scottish archaeologist who served as Evans‘s field director during the crucial early seasons (1900-1905) and remained involved for much longer. Mackenzie was responsible for the daily operations of the excavation, managing large teams of workers, and keeping meticulous records in his ‘Daybooks’. He developed a detailed understanding of Minoan pottery sequences and site stratigraphy, making crucial contributions to the interpretation of the complex site. Although often overshadowed by Evans in publications, Mackenzie’s careful fieldwork provided the foundation for Evans’s comprehensive synthesis of Minoan civilization. His role highlights the vital importance of skilled field directors in large-scale early excavations, as their detailed observations might not always receive full credit in final reports.

While Knossos was the primary focus, the British School at Athens (BSA) pursued broader activities in Crete, particularly under successive directors. David George (D.G.) Hogarth (1862-1927), BSA Director from 1897 to 1900, conducted the first systematic excavation of the Psychro Cave (often identified with the mythical Diktaion Antron) in 1899, uncovering significant votive deposits dating from the Middle Minoan to Archaic periods. In 1901, with the support of the Cretan Exploration Fund, Hogarth conducted excavations at Zakros on the far eastern coast. He investigated houses in the town area and explored pits that produced LM IA material, including early sealings and a Linear A roundel. He also briefly assisted Evans at Knossos around 1900.

Hogarth’s successor as BSA Director (1900-1906), Robert Carr (R.C.) Bosanquet (1871-1935), shifted the BSA’s major field focus towards East Crete. He initiated excavations at the important Minoan town site of Palaikastro in 1902, leading a campaign that lasted until 1906. He is also credited with excavations at Praisos, a significant site of the Eteocretans (considered indigenous Cretans). Bosanquet’s initial work established the BSA’s long-term interest in the archaeology of East Crete. After his Cretan campaigns, he began planning the BSA’s next major project in Laconia, visiting Sparta in 1903 and 1904.

Richard MacGillivray (R.M.) Dawkins (1871-1955), BSA Director from 1906 to 1914, continued the School’s work in Crete. He participated in the Palaikastro excavations and, around 1913-1914, excavated a Late Minoan settlement at Plati on the Lasithi plateau, contributing to the understanding of this inland region during the Bronze Age. The BSA also explored the Kamares Cave during this period, likely continuing Taramelli’s earlier work.

The British activities show a strategy that, while centered on Evans’s work at Knossos, deliberately diversified to explore other regions and site types. The BSA under Hogarth, Bosanquet, and Dawkins made significant contributions in East Crete (Palaikastro, Zakros, Praisos), cave sanctuaries (Psychro, Kamares), and the Lasithi plateau (Plati). This broader approach provided a more balanced perspective on Minoan Crete than would have been possible from Knossos alone, showing regional variations and the importance of different kinds of settlements and ritual centers across the island.

American Pioneers in East Crete (University of Pennsylvania Museum & ASCSA Affiliation)

American archaeological involvement in Crete during this period was characterized by a strong geographical focus on the eastern part of the island, particularly the Isthmus of Ierapetra and the Mirabello Bay region, and was closely associated with the University of Pennsylvania Museum. A key figure was Harriet Boyd Hawes (1871-1945), a pioneering archaeologist who was the first woman to direct major field excavations in Greece. In the spring of 1900, she led excavations near the village of Kavousi, discovering Late Minoan IIIC to Early Archaic settlements and cemeteries at Vronda and Kastro, and conducting a test excavation at the important Archaic site of Azoria. Her most significant work occurred between 1901 and 1904 when, supported by the American Exploration Society and affiliated with the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), she discovered and excavated the very well-preserved Minoan town of Gournia. Her comprehensive report, Gournia, Vasiliki and Other Prehistoric Sites on the Isthmus of Hierapetra, published in 1908 by the University Museum, is a foundational work in Minoan archaeology. During her time in Crete, she met British anthropologist Charles Henry Hawes, whom she later married; together they co-authored Crete, the forerunner of Greece (1909).

Working closely with Boyd Hawes and also supported by the Penn Museum were Richard Berry Seager (1882-1925) and Edith Hayward Hall Dohan (1877-1943). Seager gained his initial field experience with Boyd Hawes at Gournia. He subsequently conducted independent excavations at several key sites in the same East Cretan region. He excavated the Early Minoan site of Vasiliki, known for its distinctive mottled pottery, and published his findings with the Gournia material in 1908. In 1908, he excavated the island of Mochlos, uncovering a settlement and a rich Prepalatial cemetery that contained fine gold jewelry and stone vases. His Mochlos finds were published in 1909 and 1912. Seager also excavated the island settlement of Pseira and the important cemetery at Pacheia Ammos, known for its numerous pithos (jar) burials. There is some discrepancy in the reported dates for the Pacheia Ammos work; one source gives 1914-1915, while another suggests 1910-1911 based on the 1916 publication date. This ambiguity shows the need for careful source evaluation. Seager also worked at the Sphoungaras cemetery, located near Gournia. He lived for two decades near Pacheia Ammos, gaining extensive knowledge of the region.

Edith Hall Dohan, a classmate of Boyd Hawes, assisted at the Gournia excavations (1901-1904) and co-authored the 1908 report. She conducted her own significant excavations, also with the support of the Penn Museum and ASCSA. She excavated the cemetery site of Sphoungaras, which produced finds from the Early Minoan through Late Minoan I periods, publishing the results in 1912. Between 1910 and 1912, she excavated the prominent hilltop settlement of Vrokastro, a refuge site occupied primarily during the Late Minoan IIIC and Geometric periods (the “Dark Ages” following the collapse of Minoan palatial society). Her Vrokastro publication appeared in 1914.

Charles Henry Hawes (1867-1943), primarily an anthropologist, had a peripheral role in excavation but contributed through collaboration with Harriet Boyd Hawes. He visited Gournia in 1904 and travelled in Crete in 1905. While one source mentions his diary recording excavation work at Palaikastro (a BSA site) in 1905, the primary excavation and publication credit for Sphoungaras belongs to Edith Hall. His main contribution seems to be the co-authored 1909 book.

The American efforts, strongly linked to the University of Pennsylvania Museum and affiliated with the American School of Classical Studies at Athens (ASCSA), were thus highly concentrated in East Crete. This geographical focus, likely influenced by Boyd Hawes’s initial successes and institutional support, led to a detailed understanding of the Minoan and post-Minoan periods in that specific region. This group of early American archaeologists formed a close network, often collaborating or working on nearby sites. They also promptly published their findings through the University Museum, a practice that differed from the longer publication schedules of some other major excavations like Knossos, possibly reflecting different funding structures and institutional expectations.

The French School at Athens (École française d’Athènes – EfA): Malia, Lato, and Geometric/Archaic Sites

The French School at Athens (EfA), founded in 1846 and the oldest foreign institute in Greece, also played a significant role in Cretan archaeology, focusing primarily on the major Minoan palace site of Malia and important post-Minoan centers.

Early French involvement included the work of Joseph Demargne (1870-1912). In 1897, he conducted investigations at the Psychro Cave, finding a fragment of the offering table previously found by Evans, along with a gold diadem. He was part of the EfA team that conducted the first systematic excavations at the important Dorian city of Lato, overlooking Mirabello Bay, between 1899 and 1901. He is also associated with work at Itanos, another coastal site in the far east of Crete. Some sources also link a Demargne to early work at Malia (finding a kernos) and initiating work at Dreros in 1932. However, given Joseph Demargne‘s death in 1912, the later Dreros work (and possibly the Malia kernos find if it dates later) should likely be attributed to his nephew, Pierre Demargne (1903-2000), also a prominent archaeologist associated with the EfA.

The most significant French contribution in Minoan archaeology during this period was the long-term excavation project at Malia. Following the initial work by Iosif Hatzidakis (1919-1922), the EfA took over the site in 1922 under the direction of Fernand Chapouthier (1899-1953). Chapouthier led the excavations of the palace and surrounding town area until 1936. This work established Malia as the third-largest known Minoan palace complex and a key site for understanding Minoan architecture, urbanism, and society.

The French School at Athens (EfA) thus concentrated its major Cretan efforts on Malia, Lato, Itanos, and later Dreros. The Malia excavations, partly funded by patrons like the Goekoop de Jong family, became a leading project, showing a long-term institutional commitment that spanned decades and involved successive generations of French archaeologists. This focus on major centers – the Minoan palace of Malia and the significant Dorian city-state of Lato – allowed the EfA to make substantial contributions to the understanding of both the Bronze Age and the subsequent Iron Age and Archaic periods in Crete.

Consolidated List: Pioneer Archaeologists in Crete (Late 19th C. – 1940s)

The preceding sections have detailed the individual contributions and institutional contexts of the key figures and organizations involved in the early archaeological exploration of Crete. To provide a clear overview, the following table presents information about these early archaeologists, their affiliations, approximate periods of activity in Crete up to the 1940s, and the primary Cretan sites associated with their work during this timeframe. The table compiles data from the research material.

Table: Key Early Archaeologists Active in Crete (Late 19th Century – 1940s)

Archaeologist Name (Greek Name) | Nationality / Primary Affiliation | Approx. Dates of Activity in Crete (pre-1941) | Key Cretan Sites Excavated/Discovered/Studied (pre-1941) |

Greek | 1877-1878 | Knossos (first excavator) | |

Greek / Phil. Assoc. Heraklion, Arch. Service (Ephor) | ca. 1883 – 1920s | Idaion Antron, Amnisos, Gortyna, Tylisos (early work), Malia (Chrysolakkos, 1919-22), Dreros (prelim. invest.), Heraklion Museum (founder) | |

Italian / Italian Arch. Mission, SAIA | 1884 – ca. 1914 (d. 1930) | Idaion Antron, Gortyna (Law Code), Phaistos (1884, 1900-04), Hagia Triada (1902-14), Afratì (Arkades, 1894), Lebena, Kamares Cave (exploration), Mission Founder | |

British / Independent, Ashmolean Museum, assoc. BSA | 1894 – 1931 (excavation period) | Knossos (main excavator), Psychro Cave (1894-96), Lato (visit), Zakros (visit) | |

American / ASCSA, U. Penn Museum, Am. Expl. Soc. | 1900 – 1905 (main field seasons) | Kavousi (Vronda, Kastro, Azoria test), Gournia (discoverer/excavator), Vasiliki (co-pub) | |

Greek / Arch. Service, Heraklion Museum | ca. 1904 – 1925 (d. 1928) | Koumasa (cemetery, settlement), Tylisos (1923-25?), Dreros (1917), Heraklion Museum (founder) | |

Richard Berry Seager | American / U. Penn Museum | ca. 1903 – 1915 (d. 1925) | Gournia (assistant), Vasiliki, Mochlos (1908), Pseira, Pacheia Ammos (cemetery, 1910-11 or 1914-15), Sphoungaras |

Spyridon Marinatos (Σπυρίδων Μαρινάτος) | Greek / Arch. Service | ca. 1925 – 1938+ | Gazi, Kousses, Arkalochori Cave, Dreros (Temple of Apollo, 1935) |

Greek / Arch. Service | ca. 1930 – 1941+ | Arkalochori Cave, Poros-Katsampas | |

Luigi Pernier | Italian / SAIA | ca. 1900 – 1914 | Phaistos (1900-08, Phaistos Disk 1908), Hagia Triada (1902-08), Gortyna, Lebena |

Antonio Taramelli | Italian / SAIA | 1894 – ca. 1900s | Phaistos (1894), Miamou Cave (Neolithic), Kamares Cave (1899), Apollonia (Agia Pelagia) |

Robert Carr (R.C.) Bosanquet | British / BSA (Director) | ca. 1901 – 1906 | Praisos, Palaikastro (1902-06) |

British / BSA (Director) | ca. 1902 – 1914 | Palaikastro, Plati (Lasithi) | |

Edith Hayward Hall Dohan | American / ASCSA, U. Penn Museum | ca. 1901 – 1912 | Gournia (assistant), Sphoungaras (cemetery, pub. 1912), Vrokastro (settlement, 1910-12, pub. 1914) |

Duncan Mackenzie | British (Scottish) / BSA (Knossos Field Director) | 1900 – ca. 1929 (in Knossos) | Knossos (field director for Evans, stratigraphy, pottery) |

David George (D.G.) Hogarth | British / BSA (Director), Ashmolean Museum | ca. 1897 – 1901 (in Crete) | Psychro Cave (1899), Zakros (town, pits, 1901), Knossos (assisted Evans) |

Lucio Mariani | Italian / Independent, later SAIA affiliation? | 1893, 1896 | Various sites (exploration 1893), Knossos (visit 1896), Kamares Ware study, Relief Pithoi study |

Luigi Savignoni | Italian / Italian Arch. Mission | 1893, ca. 1901 | West Crete (exploration 1893), Publication of Halbherr’s pithos finds (1901) |

Roberto Paribeni | Italian / SAIA | ca. 1902 – 1905 (at Hagia Triada) | Hagia Triada |

Enrico Stefani | Italian / SAIA | ca. 1902 – 1914 (at Hagia Triada) | Hagia Triada |

Gaetano De Sanctis | Italian / Italian Arch. Mission, SAIA | 1893, 1908, 1910-14 | West Crete (exploration 1893), Afratì (Arkades, 1908), Hagia Triada (1910-14 campaign), Gortyn (inscriptions) |

Italian / Venetian Institute, assoc. SAIA | 1900 – 1902 (main survey), early 20th C. | Gortyn (briefly involved in research), Venetian monuments survey | |

Joseph Demargne | French / EfA | ca. 1897 – 1901 | Psychro Cave (1897), Lato (1899-1901), Itanos |

Fernand Chapouthier | French / EfA | 1922 – 1936 | Malia (Palace, town) |

Antonio Minto | Italian / SAIA | 1909 – 1922 | Phaistos (Christos Effendi fortifications) |

Italian / SAIA | 1924 (main pre-1940 work) | Afratì (Arkades, Geometric/Archaic settlement & necropolis) | |

Vasileios Theofaneidis (Βασίλειος Θεοφανείδης) | Greek / Arch. Service (Ephor) | 1935 – 1941 | Western Crete |

Charles Henry Hawes | British / Anthropologist, assoc. BSA | ca. 1904 – 1905 (visits/travel) | Gournia (visit), Palaikastro |

Note: Dates reflect primary activity periods in Crete relevant to the pre-1941 scope. Some individuals had longer careers with later work not detailed here. Affiliations indicate the primary institutional connection for their Cretan work. SAIA = Scuola Archeologica Italiana di Atene; BSA = British School at Athens; ASCSA = American School of Classical Studies at Athens; EfA = École française d’Athènes (French School at Athens).

This table shows several patterns. The main period of discovery and excavation occurred primarily between approximately 1900 and 1914, coinciding with the existence of the Cretan State and the establishment or strengthening of the foreign schools. There is a clear geographical distribution: Italian archaeologists were primarily active in the Mesara (Phaistos, Hagia Triada, Gortyn); the British focused on Knossos and East Crete (Palaikastro, Zakros); American teams concentrated heavily in the Isthmus of Ierapetra and Mirabello Bay (Gournia, Mochlos, Pseira, Vrokastro); and the French centered their efforts on Malia and Lato. Greek archaeologists, while initially focused around Heraklion and key sites like Tylisos, gradually expanded their activities across the island, often investigating sites or periods that complemented the large foreign projects. The information highlights the international nature of early Cretan archaeology, which was influenced by a combination of national interests, institutional support, and the intellectual curiosity of individual scholars.

Conclusion: Foundations of Cretan Archaeology

The period from the late 19th century to the 1940s represents a foundational period in Cretan archaeology. In a few decades, the island changed from being archaeologically little-known, primarily understood through myth and scattered classical references, into a recognized center of a major Bronze Age civilization. The archaeologists, both Cretan and foreign, played a key role in this change. Their efforts led to the discovery and initial excavation of the major Minoan palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and later Zakros, along with significant town sites like Gournia and Palaikastro, and important administrative centers like Hagia Triada. Cemeteries with significant finds were excavated at sites such as Mochlos, Pacheia Ammos, Sphoungaras, and Koumasa, providing insights into burial customs and artistry. Sacred caves (Idaion Antron, Psychro, Kamares, Arkalochori) and peak sanctuaries provided information about Minoan religion. Furthermore, significant post-Minoan sites like Lato, Dreros, Vrokastro, Gortyn, and Afratì were investigated, providing links between the Bronze Age and the Classical period. The discovery of unique artifacts like the Phaistos Disk, the Snake Goddess figurines from Knossos, the Hagia Triada sarcophagus, and the inscribed tablets in Linear A, Linear B, and Cretan Hieroglyphs offered new ways to understand Minoan society, administration, and possibly, language.

This period also saw the gradual development of archaeological methodology. While early work sometimes resembled a search for valuable objects, individuals like Duncan Mackenzie at Knossos applied more systematic approaches to excavation, emphasizing the importance of stratigraphy and pottery sequences for establishing chronology. The development of typology, classifying artifacts based on form and style, became an important tool for dating finds. Although methods were often basic by modern standards, and large-scale clearances sometimes prioritized architecture over detailed context recording, these early efforts represented a significant advance over previous antiquarian approaches. The prompt publication by some American excavators also set a valuable precedent, although the very large scale of sites like Knossos led to much longer publication timelines.

The legacy of these early archaeologists is considerable. They provided the essential basis for all subsequent archaeological research in Crete. Evans‘s chronological framework still provides the basic structure for Minoan studies. The key sites they identified remain central to the field. The collections they gathered form the core of the Heraklion Archaeological Museum and other major museums worldwide. The institutional structures they established – the foreign schools (SAIA, BSA, ASCSA, EfA) and the Greek Archaeological Service with its Ephorates – continue to influence research, training, and heritage management on the island today.

However, a critical perspective acknowledges the complexities of this early period. Early methods, while advancing the field at the time, were often destructive, and interpretations could be influenced by the dominant intellectual ideas and biases of the excavators. Evans‘s extensive and sometimes speculative reconstructions at Knossos remain controversial. Furthermore, the relationship between foreign archaeologists and local Cretan communities, including excavation workers, was often hierarchical, reflecting the broader colonial context of the period. The contributions of local collaborators and skilled workers were frequently not fully recognized or were ignored in official publications.

The archaeological landscape of early 20th century Crete was thus shaped by a complex interaction of collaboration and competition. Rivalry between national schools and individuals undoubtedly increased the pace of discovery, as each sought prestige through significant finds. Yet, progress also depended on collaboration, both formal and informal, between the foreign missions and the Greek authorities and scholars who assisted their work, granted permits, and contributed their own expertise. This complex mixture of competition and cooperation ultimately led to the rapid discovery of Crete’s ancient past. While leaving many questions unanswered and large areas unexplored, the work undertaken between the 1870s and the 1940s firmly established the foundations for the current understanding of ancient Crete.