Chapter 1: Introduction – The Initial Target and Change of Plans

1.1 SOE’s Strategic Context in Occupied Crete

Following the dramatic and costly German airborne invasion, Operation Mercury, in May 1941, the Greek island of Crete fell under Axis occupation. Its strategic position in the Eastern Mediterranean made it a valuable asset for German forces, serving as a base that influenced operations in North Africa and controlled vital sea lanes. Despite the Allied evacuation, resistance on the island began almost immediately, characterized by fierce determination from the local population, including civilians who attacked German paratroopers during the initial invasion.

Into this volatile environment, the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) inserted agents. Established by Winston Churchill with the mandate to “set Europe ablaze,” SOE’s role in Crete was multifaceted. Agents were tasked with liaising with and supporting the burgeoning Cretan resistance movements, gathering crucial intelligence, conducting sabotage operations against German forces and infrastructure, and assisting Allied personnel evade capture or escape the island. The Cretan resistance, aided by SOE, inflicted damage on German morale and tied down significant occupation forces. However, this resistance came at a high price, as German occupation forces frequently responded with brutal reprisals against the civilian population even before the events of 1944.

1.2 Targeting General Müller: “The Butcher of Crete”

In late 1943, within SOE circles in Cairo, a particularly audacious plan began to take shape: the abduction of the German commander of the 22nd Air Landing Division (22. Luftlande-Infanterie-Division) and military governor of the Heraklion sector, General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller. Müller was not just a high-ranking officer; he was a figure of profound hatred and fear among the Cretan populace. His ruthless methods and direct responsibility for numerous atrocities had earned him the grim moniker “The Butcher of Crete”.

Müller’s command was stained by acts of extreme brutality. These included mass executions of civilians in villages across Crete, such as the Viannos massacres in September 1943 where over 500 civilians were killed over three days in some 20 villages. Other locations associated with massacres under his command or during his tenure include Anogeia, the Amari villages (later site of the Kedros Holocaust), Damasta, Skourvoula, and Malathyros. Furthermore, in October 1943, Müller ordered the execution of over one hundred captured Italian army officers on the island of Kos who refused to side with the Germans after Italy’s armistice with the Allies. He was also known for the conscription of civilians into forced labor units.

The SOE’s rationale for targeting Müller was clear. His removal would eliminate a commander known for exceptional cruelty, potentially easing the burden on the Cretan people. More significantly, the successful abduction of such a notorious figure was expected to deliver a powerful blow to German prestige and provide a substantial boost to the morale of the Cretan resistance and the Allied cause in the region. The operation aimed for propaganda value, demonstrating the reach and capability of Allied special forces and their Cretan allies deep within occupied territory.

1.3 The Unforeseen Change: General Kreipe Becomes the Objective

The plan to abduct Müller, however, was disrupted by personnel changes within the German command structure. Around March 1, 1944, before the full SOE abduction team could be assembled on the island, General Müller was replaced as commander of the 22nd Air Landing Division by Major General Heinrich Kreipe. Müller moved to become the overall commander of Fortress Crete (Festung Kreta) based in Chania, replacing General Bruno Bräuer.

Major Patrick Leigh Fermor, the SOE officer leading the operation who had already parachuted onto the island in February, learned of this change while awaiting the arrival of the rest of his team. Faced with the choice of aborting the mission or proceeding with the new commander as the target, Leigh Fermor advocated for the latter. Despite knowing little about Kreipe’s character or reputation at the time, he argued that the capture of any German general officer would achieve the primary objective of boosting Allied and Cretan morale and demonstrating the resistance’s effectiveness. SOE Cairo concurred, and the operation, codenamed “Landmark,” was redirected towards General Kreipe.

Heinrich Kreipe was a different figure from Müller. A career soldier decorated in World War I, he was not associated with the same level of systematic brutality that defined Müller’s command. While still a representative of the occupying power, he lacked the specific notoriety that had made Müller the “Butcher of Crete”. Some accounts even suggest Kreipe was disliked within his own officer corps for his perceived pettiness and rudeness, leading to subdued celebrations in the officers’ mess upon news of his abduction.

This change in target significantly altered the nature of the operation. What was initially conceived partly as a punitive action against a known war criminal transformed into an operation primarily focused on symbolic and propaganda impact. The objective became demonstrating the vulnerability of the German command and the prowess of the Anglo-C Cretan resistance, rather than removing a specific perpetrator of atrocities.

Furthermore, the decision to proceed with Kreipe carried a significant, albeit perhaps underestimated, risk. While the abduction itself might boost morale, it left Müller, the architect of previous massacres, still in a position of authority on the island (now as Fortress Commander). The potential for Müller to eventually order even harsher reprisals in response to the abduction or continued resistance activities remained. This danger was not unforeseen; senior SOE executive Bickham Sweet-Escott had opposed the original plan to capture Müller precisely because of the high probability of devastating German reprisals against the Cretan civilian population. Capturing the relatively less offensive Kreipe did nothing to mitigate this underlying threat, and indeed, Müller would later return to oversee brutal collective punishments in August 1944.

Chapter 2: Planning and Preparations

2.1 The Architects: Leigh Fermor, Moss, and SOE Cairo

The plan to abduct a German general from Crete originated in the SOE’s Cairo headquarters in late 1943. While earlier discussions had considered targeting previous commanders like Generals Andrae and Bräuer, the specific operation targeting the commander of the 22nd Division was primarily conceived by two young British SOE officers: Major Patrick Leigh Fermor and Captain William Stanley “Billy” Moss.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, aged 29 at the time of the operation, was already a seasoned operative with extensive experience on Crete. Having participated in the Battle of Crete in 1941 and subsequently returning as an SOE agent, he had spent over two years living clandestinely in the mountains, often disguised as a Cretan shepherd under the aliases ‘Michalis’ or ‘Filedem’. His fluency in Greek and deep understanding of the island’s culture and terrain, along with established contacts within the resistance, made him uniquely suited to lead such a mission.

Captain W. Stanley Moss was younger, only 22, and possessed less direct experience in Crete but was characterized by an adventurous spirit and eagerness for action. He had served with the Coldstream Guards before joining SOE in Cairo. Leigh Fermor selected Moss as his second-in-command for the operation.

The plan was submitted to the SOE command structure in Cairo, headed by Brigadier Karl Vere Barker-Benfield. It garnered widespread enthusiasm, seen as a potentially high-impact operation. However, notable opposition came from Bickham Sweet-Escott, a senior executive on the Special Operations Committee, who argued forcefully that the potential morale boost was outweighed by the almost certain risk of brutal German reprisals against the Cretan population. Despite these concerns, the plan was approved in late 1943 or early 1944.

2.2 Forging the Alliance: Collaboration with the Cretan Resistance

From the outset, the operation was conceived as a joint effort between British SOE agents and the Cretan resistance. Leigh Fermor and Moss were joined in the core abduction team by two experienced Cretan SOE agents: Georgios Tyrakis and Emmanouil Paterakis.

Beyond this initial quartet, the success of the mission depended heavily on a wider network of Cretan resistance fighters and civilians. Key figures recruited during the planning and execution phases included Michail Akoumianakis (whose house provided a crucial observation point), Antonios Papaleonidas (nicknamed ‘Wallace Beery’) and his brother Grigorios, Grigorios Chnarakis, Ilias Athanasakis (who manned an observation post overlooking German HQ), Efstratios Saviolakis (‘Saviolis’), Dimitrios Tzatzadakis (‘Tzatzas’), Nikolaos Komis, and Antonios Zoidakis. The renowned Cretan runner and resistance member, George Psychoundakis, later played a vital role in re-establishing communications.

The contribution of these Cretan allies was indispensable. They provided intimate local knowledge, crucial intelligence on German movements and routines, logistical support including safe houses and food, armed escorts, and acted as guides through the treacherous mountain terrain. Leigh Fermor himself consistently emphasized that the majority of those involved in the operation were Cretan, acknowledging their courage and the immense risks they undertook.

Table 1: Key Personnel Involved in Operation Landmark

Name | Affiliation | Role(s) |

Patrick Leigh Fermor | British SOE | Leader, Planner, Abductor |

W. Stanley Moss | British SOE | Second-in-Command, Planner, Abductor, Driver |

Georgios Tyrakis | Cretan Resistance/SOE | Abductor, Escort |

Emmanouil Paterakis | Cretan Resistance/SOE | Abductor, Escort |

Michail Akoumianakis | Cretan Resistance | Support, Intelligence (House near Villa) |

Antonios Papaleonidas | Cretan Resistance | Abduction Team Member, Escort |

Grigorios Papaleonidas | Cretan Resistance | Abduction Team Member, Escort |

Grigorios Chnarakis | Cretan Resistance | Support Team |

Ilias Athanasakis | Cretan Resistance | Lookout (German HQ) |

Efstratios Saviolakis | Cretan Resistance | Abduction Team Member, Escort |

Dimitrios Tzatzadakis | Cretan Resistance | Lookout (Signal) |

Nikolaos Komis | Cretan Resistance | Abduction Team Member |

Antonios Zoidakis | Cretan Resistance | Abduction Team Member |

George Psychoundakis | Cretan Resistance | Runner, Facilitated Communications |

Numerous unnamed guides, runners, villagers | Cretan Resistance/Civilians | Shelter, Food, Intelligence, Guidance |

2.3 Laying the Groundwork: Intelligence, Reconnaissance, and Logistics

Top row from left to right: Efstratios Saviolakis, Emmanouil Paterakis, Antonis Papaleonidas, Georgios Tyrakis,Nikolaos Komis

Bottom row: Grigorios Chnarakis, Patrick Leigh Fermor, W. Stanley Moss

The operational phase began with the insertion of the team. Leigh Fermor successfully parachuted onto the Katharo plateau in eastern Crete on February 4, 1944, but adverse weather forced the aircraft carrying Moss, Tyrakis, and Paterakis to return to Egypt. After numerous failed attempts, the rest of the core team finally landed by motor launch on the southern coast at Tsoutsoura on April 4, 1944.

During the intervening two months, Leigh Fermor re-established contact with local resistance networks and began reconnaissance. The reunited team established a base in a cave system above the village of Kastamonitsa. A crucial element of the reconnaissance involved Leigh Fermor, disguised as a Cretan shepherd, traveling by local bus to observe General Kreipe’s residence, the Villa Ariadne in Knossos, and his divisional headquarters in Ano Archanes, approximately 5 miles away. The Villa Ariadne, enclosed by wire barriers and heavily guarded, was deemed too difficult for a direct assault.

Intelligence gathering focused on Kreipe’s daily routine. It was learned that he regularly traveled by car between his residence and headquarters, often returning late at night, sometimes after playing bridge. This predictable pattern made him vulnerable to an ambush. The team surveyed the route and identified an ideal spot: a T-junction (referred to as Point A) on the road from Archanes joining the main road to Heraklion, near the villages of Skalani or Patsides, where vehicles were forced to slow considerably. Local support was vital: Michail Akoumianakis’s house across from the Villa Ariadne provided an observation point, as did a cottage near Skalani used by another collaborator. Ilias Athanasakis established a lookout post overlooking the German headquarters to signal Kreipe’s departure.

Logistical preparations were meticulous. Akoumianakis procured two authentic summer uniforms of the German Feldgendarmerie (Military Police), complete with insignia and sidearms. Weapons, including a cosh (truncheon) for neutralizing the driver, were readied. A signaling system, involving either an electric bell triggered by a wire or torch flashes, was arranged to alert the ambush party of the car’s approach.

The planning phase was not without challenges. The team’s wireless radio broke down, forcing reliance on slower and less secure communication via runners. They also received a threat from a local commander of the communist-aligned ELAS resistance group, demanding they leave the area, though this threat was ultimately neutralized through careful diplomacy by Leigh Fermor. Several planned attempts had to be aborted due to adverse weather or unexpected changes in Kreipe’s schedule.

The detailed planning, particularly the reconnaissance of Kreipe’s routine and the route, underscores the vital importance of the Cretan contribution. Identifying the optimal ambush point, understanding Kreipe’s predictable movements, and even acquiring the necessary German uniforms were all facilitated by local knowledge and connections. This deep integration with the local resistance network was a fundamental prerequisite for the operation’s design and eventual execution.

Chapter 3: The Abduction, Evasion, and Extraction

3.1 Execution: The Ambush and Capture (Night of April 26, 1944)

On the night of April 26, 1944, after several frustrating postponements, the conditions were finally right. Positioned near Point A – the pre-selected T-junction or bend near Archanes/Skalani/Patsides – the abduction team waited. At approximately 9:30 PM, the lookout, Dimitrios Tzatzadakis, signaled (likely with torch flashes) that General Kreipe’s staff car was approaching, crucially, without an escort.

Major Leigh Fermor and Captain Moss, disguised in the acquired Feldgendarmerie uniforms, stepped into the road. As the Opel slowed for the junction, Moss waved a traffic baton and shouted “Halt!”. Leigh Fermor approached the passenger side where General Kreipe sat. Accounts vary slightly on the precise sequence, but essentially, as Kreipe possibly reached for identification papers or questioned the stop, Leigh Fermor opened the door, jumped in, and held the General at gunpoint.

Simultaneously, the Cretan members of the team converged on the vehicle. Moss swiftly neutralized the driver, Sergeant Albert Fenske. Historical accounts differ on whether Fenske was killed or knocked unconscious with Moss’s cosh. Given Leigh Fermor’s stated intention to conduct a “bloodless” operation, the latter is often favored, though the situation was undoubtedly violent and chaotic. Fenske was dragged away by some of the Cretans. General Kreipe, struggling and protesting, was quickly overpowered and bundled into the back seat by Emmanouil Paterakis, Georgios Tyrakis, and possibly Efstratios Saviolakis.

According to accounts by Moss and Leigh Fermor, once Kreipe was secured, he was offered parole: if he promised not to shout or attempt escape, he would be treated honorably as a fellow officer rather than strictly as a prisoner. Kreipe reportedly gave his word immediately. Kreipe himself later disputed having given his parole under these circumstances.

3.2 Through the Checkpoints: An Audacious Bluff

With Kreipe subdued in the back seat, Moss took the driver’s position, and Leigh Fermor sat in the front passenger seat, donning the General’s distinctive peaked cap to complete the impersonation. The car sped off towards Heraklion, the island’s main city, embarking on perhaps the most audacious phase of the operation.

For the next hour and a half, the commandeered vehicle successfully navigated an astonishing 22 German military checkpoints within and around Heraklion. This remarkable feat was not merely attributable to luck or the darkness. The planners had astutely leveraged intelligence about German military culture and General Kreipe’s personality. Kreipe was known among the garrison troops for his impatience and rudeness when stopped at checkpoints. Anticipating this, Leigh Fermor, wearing the General’s cap, likely offered curt salutes or gestures, while Moss drove assertively. The German sentries, recognizing the General’s car and pennants, and likely intimidated by his reputation or adhering strictly to hierarchical deference, waved the vehicle through without proper inspection, prioritizing the avoidance of an officer’s displeasure over strict security protocols. This calculated exploitation of psychological factors and established routines was crucial to the bluff’s success.

Having passed through the gauntlet of Heraklion’s checkpoints, the car headed west along the road towards Rethymno before turning off. Moss stopped the car near a steep mountain track leading towards the village of Anogeia. Here, the party began to split up according to plan. Moss, Paterakis, Tyrakis, Saviolakis, and the captive General began the arduous trek into the mountains on foot.

Leigh Fermor, meanwhile, drove the car further on to abandon it. Sources differ on the exact location: some state it was left near the hamlet of Heliana, while others indicate it was left on the coast to create the false impression of an immediate seaborne evacuation. Inside or near the abandoned vehicle, Leigh Fermor deliberately left evidence designed to mislead the Germans and, crucially, to protect the local population from reprisals. This included a note explicitly stating the abduction was a British special forces operation conducted without local assistance, along with items like British cigarettes, a commando beret, and an English-language paperback novel. Leigh Fermor then rejoined the main party heading into the mountains.

3.3 The Mountain March: Traversing Psiloritis

The journey that followed was an epic feat of endurance and evasion, lasting approximately 18 to 20 days, from the night of April 26/27 until the extraction on May 14. The primary route led the party southwards across the formidable spine of Crete, traversing the rugged and snow-capped peaks of the Psiloritis mountain range, also known as Mount Ida. The terrain was challenging, demanding stamina and resilience from both the captors and their captive.

3.4 The Network of Courage: Civilian Support and Shelter in Cretan Villages

The successful evasion of thousands of searching German troops over nearly three weeks would have been impossible without the extensive and courageous support of the Cretan resistance network and the civilian population. The abduction party relied entirely on this network for survival and movement.

Numerous villages and remote locations provided critical aid. The party found initial rest in Anogeia shortly after abandoning the car. They utilized cave systems (like the one above Kastamonitsa used during planning and another near Tapais) and remote shepherds’ huts, known as mitata, for shelter. As they moved south through the Psiloritis and descended towards the Amari Valley, they received assistance in villages like Pantanassa, where crucial radio contact was re-established thanks to runner George Psychoundakis and SOE officer Dick Barnes, and Patsos, where the group temporarily split for safety. Later staging points included Karines, Vilandredo, Asi Gonia, Agia Paraskevi (where they received intelligence updates), and Fotinos.

The assistance provided took many forms: secure shelter in homes, caves, or huts; provision of food and water; critical intelligence regarding German patrol locations and search patterns; expert guidance through the complex mountain paths by local shepherds and resistance fighters who knew the terrain intimately; and communication support through runners when the team’s wireless failed.

The risks undertaken by every Cretan who offered aid were immense. The German command reacted swiftly to the abduction, dropping leaflets over villages like Anogeia as early as April 27, threatening severe reprisals if the General was not returned within three days. The established German policy of collective punishment meant that assisting the escapees could lead to execution, imprisonment, and the destruction of homes and entire villages. Despite these mortal dangers, the Cretan code of honor (philotimo) and resistance spirit prevailed. The abduction party benefited from an extraordinary level of solidarity and secrecy; not a single villager is known to have betrayed them to the Germans. This unwavering support network functioned as a human shield and logistical lifeline, enabling a small group to evade a massive manhunt in occupied territory. The operation was, in this evasion phase, fundamentally a joint Anglo-Cretan success, predicated on local bravery.

3.5 Outwitting the Wehrmacht: Evasion Tactics

Facing a German search operation involving potentially up to 30,000 troops and reconnaissance aircraft, the abduction team employed various evasion tactics. Constant movement was key, primarily at night or through terrain inaccessible to large German patrols. They relied heavily on the expertise of their Cretan guides, who navigated secret paths and possessed up-to-date knowledge of German positions. When their wireless failed, messages were relayed via trusted runners. At times, the party split into smaller groups to reduce visibility or cover more ground. They received timely warnings from the resistance network about nearby German patrols, allowing them to take cover or change course.

Despite these precautions, there were several close calls. On one occasion, a German patrol passed within a mile of their cave hideout. The first planned evacuation attempt from a southern beach had to be aborted when a messenger brought news that German troops, searching for the party, had coincidentally occupied the rendezvous site, forcing a retreat back into the mountains. Near Asi Gonia, they learned German forces were only an hour behind them.

3.6 Escape: Rendezvous and Extraction (May 14, 1944)

After nearly three weeks on the run, communication with SOE Cairo was re-established, and a new extraction plan was formulated. The final leg of the journey brought the party, now sometimes accompanied by cheering partisans and peasants in liberated mountain areas, towards the designated pickup point on the south coast. They were escorted in the final stages by guerrillas from the Rodakino region.

The chosen location was a beach in the vicinity of Rodakino, Peristeres beach. On the night of May 14, 1944, at around 10:00 or 11:00 PM, a British Royal Navy Motor Launch (ML 842, commanded by Brian Coleman) arrived offshore. A unit from the Special Boat Service (SBS) was also present, landed to provide covering fire if necessary, although their intervention proved unneeded as the extraction proceeded without detection.

Major Leigh Fermor, Captain Moss, General Kreipe, and their core Cretan team boarded the launch and departed Cretan shores undetected. They were transported across the Mediterranean to the safety of Allied-controlled Egypt, arriving at the port of Mersa Matruh the following day, May 15, 1944.

Chapter 4: German Reprisals

Kentros mountain, Vrysses village, Kardaki village and at the distance Gerakari village

4.1 The German Response: Search Operations and Threats

The abduction of a divisional commander from under the noses of the substantial German garrison on Crete provoked an immediate and massive response. Upon discovering General Kreipe’s disappearance and the abandoned car, the German command launched large-scale search operations across the island. Thousands of troops, estimated by some sources to be as high as 30,000, were mobilized to scour the mountains and valleys, attempting to block potential escape routes. Reconnaissance aircraft were deployed to search from the air.

Simultaneously, the German authorities issued stark warnings to the civilian population. As early as April 27, leaflets were dropped, particularly over the village of Anogeia where the party had briefly rested, demanding Kreipe’s return within three days and explicitly threatening reprisals if he was not surrendered. General Bruno Bräuer, who was the Commander of Fortress Crete at the time of the abduction, initially threatened harsh retaliatory measures. However, perhaps influenced by the lack of bloodshed during the abduction itself and the notes left by Leigh Fermor attempting to deflect blame onto British forces alone (notes the Germans ultimately chose to ignore), large-scale massacres did not immediately follow in May or June 1944.

While the specific intelligence methods are not fully detailed, the German forces eventually deduced the general escape route taken by the abduction party through the central mountains. The subsequent targeting of villages like Anogeia and those in the Amari Valley/Kedros region for reprisals strongly suggests that German intelligence, through interrogations, observation, analysis of resistance activity patterns, or potentially information from collaborators (though none are implicated in betraying the main party), identified these areas as having harbored or facilitated the escapees.

4.2 Unleashing Vengeance: The Kedros Holocaust and the Razing of Anogeia

The situation escalated dramatically later that summer. On July 1, 1944, or possibly returning specifically for this purpose in August, General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller – “The Butcher of Crete” – replaced Bräuer as the overall Commander of Fortress Crete. Müller was reportedly determined to exact punishment on the Cretan population for their continued resistance and perceived support for the Kreipe abduction. In August 1944, months after the abduction itself, Müller unleashed a wave of brutal reprisals against civilian communities suspected of aiding the resistance.

The Razing of Anogeia: Beginning on August 13, 1944, German forces systematically destroyed the large mountain village of Anogeia. Müller’s official order cited multiple justifications: Anogeia being a center of British intelligence; the alleged murder of German soldiers from the Yeni-Gave garrison by Anogeians; their involvement in the Damasta sabotage (a separate resistance operation); sheltering guerrillas from various groups; and serving as a passage point for Kreipe’s kidnappers. German troops surrounded the village, allowed most men to flee to the mountains, forcibly evacuated the women and children to the Mylopotamos area, and then executed approximately 25 elderly, infirm, or defiant villagers who remained. Over the next 23 days, until early September, German soldiers systematically looted, burned, and dynamited every single one of the village’s 940 houses, destroyed the school, desecrated churches by using them as stables, demolished shepherd huts in the surrounding area, and confiscated all livestock.

The Kedros Holocaust (Holocaust of Amari): Starting on August 22, 1944, Müller ordered another major reprisal operation targeting villages in the Amari Valley, situated at the foot of Mount Kedros, south of the Psiloritis range. This campaign, often referred to as the “Holocaust of Kedros” or “Holocaust of Amari,” involved the mass execution of civilians – one specific count mentions 164 civilians killed. German infantry systematically destroyed villages, looted property, and destroyed livestock and harvests. Sources indicate this operation was intended not only as retaliation but also to intimidate the population and deter guerrilla attacks during the planned German withdrawal and consolidation of forces towards Chania.

The villages subjected to these collective punishments in August 1944 included:

- Anogeia: Completely razed, inhabitants executed or displaced.

Villages of the Kedros/Amari region: Subjected to mass executions, razing, and looting. While the term encompasses multiple villages, specific executions occurred at Skourvoula on August 14 (prior to the main Kedros operation but part of the same wave of reprisals under Müller), where 36 civilians (including women) from Skourvoula itself and the nearby villages of Magarikari and Kamares were shot. The broader Kedros operation starting August 22 targeted nine villages in total.

Table 3: Villages Subjected to Major Reprisals (August 1944)

Village Name | Region | Date(s) of Reprisal | Nature of Reprisal | Commander Responsible |

Anogeia | Psiloritis Foothills | Aug 13 – Sep 5, 1944 | Razing, Mass Execution (~25), Looting, Displacement | Müller |

Skourvoula | Psiloritis Foothills/Messara | Aug 14, 1944 | Mass Execution (36 civilians, incl. from nearby villages) | Müller |

Kamares | Psiloritis Foothills/Amari | Aug 14, 1944 | Inhabitants executed at Skourvoula | Müller |

Magarikari | Psiloritis Foothills/Amari | Aug 14, 1944 | Inhabitants executed at Skourvoula | Müller |

Villages of Kedros/Amari Valley* | Amari Valley / Mt Kedros | Aug 22, 1944 onwards | Mass Execution (164+), Razing, Looting, Destruction | Müller |

*Note: The Kedros/Amari operation involved multiple villages (reportedly nine).

4.3 Command Responsibility for Atrocities

The primary responsibility for ordering and overseeing the brutal reprisals of August 1944 lies unequivocally with General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller. His actions during this period solidified his reputation as “The Butcher of Crete.”

After the war, Müller was captured by the Red Army in East Prussia and subsequently extradited to Greece. He was tried by a Greek military court in Athens for war crimes, including the Viannos massacres, the Kedros Holocaust, and other atrocities involving the killing of hostages and civilians. Found guilty, Müller was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad on May 20, 1947, alongside General Bruno Bräuer, the former Fortress Commander he had replaced.

The significant delay between the Kreipe abduction in late April/early May and the major reprisals in August suggests a complex causality. While the abduction undoubtedly angered the German command and was cited as a justification for the destruction of Anogeia, it was likely not the sole trigger for the August atrocities. Müller’s return to overall command, his established propensity for brutality, ongoing Cretan resistance activities (such as the Damasta sabotage, also cited in the Anogeia order), and the German strategic decision to consolidate forces and intimidate the population during their retreat towards Chania all appear to have converged in August 1944, leading to this final, devastating wave of collective punishment. The reprisals were less an immediate, direct response to the abduction itself, and more a culmination of Müller’s brutal command philosophy applied during a period of heightened resistance and German strategic repositioning.

Chapter 5: Aftermath and Legacy

5.1 Immediate Consequences: Morale, Command, and the Resistance

The successful abduction of General Kreipe sent shockwaves through the German garrison on Crete and resonated across Allied and occupied territories. For the Germans, it represented a significant blow to morale and a considerable loss of face. The ease with which a divisional commander could be snatched from his car on a supposedly secure island undermined the sense of German control and invincibility. Allied propaganda quickly capitalized on the event, portraying it as a daring Allied coup and even suggesting Kreipe might have defected. Within the German officers’ mess itself, the reaction was reportedly muted, even celebratory among those who disliked Kreipe’s leadership style.

In terms of command structure, Kreipe was promptly replaced as commander of the 22nd Division, initially by Generalleutnant Helmut Friebe on May 1, 1944. More consequentially, the event likely contributed to the decision to eventually reinstate General Müller as the overall commander of Fortress Crete later that summer. This change ultimately led to a period of intensified brutality and the devastating reprisals in August 1944, marking a harsher phase of the occupation in the affected regions.

For the Cretan resistance movement, the abduction was an unqualified triumph. It served as a major morale booster, demonstrating their capability, daring, and effective collaboration with Allied forces. The operation significantly raised the standing of the resistance, showcasing their ability to strike at the heart of the German command structure and successfully evade capture against overwhelming odds. It became a potent symbol of defiance and inspired continued opposition to the occupation.

5.2 Operation Landmark in Historical Context: Strategic Value vs. Symbolic Victory

Despite its operational brilliance and immediate impact on morale, the long-term strategic significance of Operation Landmark remains a subject of historical discussion. Many assessments conclude that its primary value was symbolic and propagandistic, rather than yielding tangible military advantages. General Kreipe himself, once interrogated in Cairo and later in POW camps, provided little intelligence of significant value to the Allied war effort. The balance of power on Crete was not fundamentally altered; the Germans continued their occupation, albeit with damaged pride.

However, a counter-argument exists regarding the broader context. The abduction was a high-profile manifestation of the persistent Cretan resistance. This resistance, sustained throughout the occupation and bolstered by SOE support and operations like the Kreipe kidnapping, successfully tied down a substantial German garrison on the island, variously estimated at 20,000 to 50,000 troops depending on the period. These forces were thus unavailable for deployment on other critical fronts, such as North Africa or the Eastern Front. In this sense, while the abduction itself may not have been strategically decisive, it contributed to the overall Allied strategy of attrition and resource diversion.

Nevertheless, the success of the abduction must be weighed against its tragic aftermath. Leigh Fermor and Moss had aimed for a “bloodless” operation that would avoid reprisals against the civilian population. While the immediate aftermath under General Bräuer saw threats but not mass killings, the later return of General Müller led directly to the brutal collective punishments of August 1944, including the razing of Anogeia and the Kedros Holocaust. This outcome raises profound ethical questions about the operation’s justification, questions debated even within SOE at the time, as exemplified by Sweet-Escott’s initial opposition and later concerns voiced by officers like Dunbabin and Stockbridge.

The Kreipe abduction starkly illustrates the inherent tension within SOE’s mission. The directive to actively resist and disrupt the enemy (“set Europe ablaze”) often carried the foreseeable consequence of vicious enemy reprisals against the very populations SOE sought to liberate. The attempt by Leigh Fermor to mitigate this risk by leaving notes claiming sole British responsibility proved futile against a commander like Müller, predisposed to collective punishment. Operation Landmark thus stands as a compelling case study of the complex moral calculus involved in clandestine warfare and resistance support during World War II, highlighting the difficult balance between operational audacity and the protection of civilians.

5.3 Enduring Memory: Commemorations, Literature, and Historical Perspectives

Operation Landmark remains one of the most celebrated and remembered special operations of World War II, its legacy preserved through memorials, literature, film, and historical assessments.

In Crete: The abduction is revered as a heroic chapter in the island’s long history of resistance against occupiers. It stands as a symbol of Cretan courage, resilience, and effective cooperation with Allied forces. The participants, particularly the Cretan members of the team, are honored as heroes. The event is physically commemorated by a distinctive memorial featuring barbed wire sculptures, designed by Manolis Tzobanakis, located at the abduction site near the Patsides junction. While specific commemorations focus on the abduction, the broader annual events marking the Battle of Crete often encompass the spirit of resistance demonstrated throughout the occupation, including Operation Landmark.

In Britain: The operation captured the public imagination as a daring “commando-style” raid, epitomizing ingenuity and bravery behind enemy lines. Patrick Leigh Fermor and W. Stanley Moss became well-known figures, celebrated for their roles. Both officers received decorations for their actions: Leigh Fermor was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), and Moss received the Military Cross (MC).

In Germany: The event is acknowledged in historical accounts of the occupation of Crete. While likely viewed primarily as a successful enemy operation and an embarrassment, its memory is inevitably intertwined with the subsequent, brutal reprisals ordered by Müller. There is no specific German memorial related to the abduction itself; the main German war cemetery at Maleme commemorates the heavy losses suffered during the initial 1941 invasion.

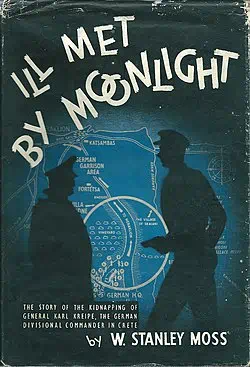

The story of the abduction has been immortalized in literature, most notably through the accounts of the two lead SOE participants. W. Stanley Moss published his contemporary diary-based account, “Ill Met by Moonlight,” in 1950, which became a bestseller. Decades later, Patrick Leigh Fermor’s own detailed account, “Abducting a General: The Kreipe Operation and SOE in Crete,” drawing on his wartime reports and recollections, was published posthumously in 2014. Other historical works, such as Rick Stroud’s “Kidnap in Crete,” have also examined the operation.

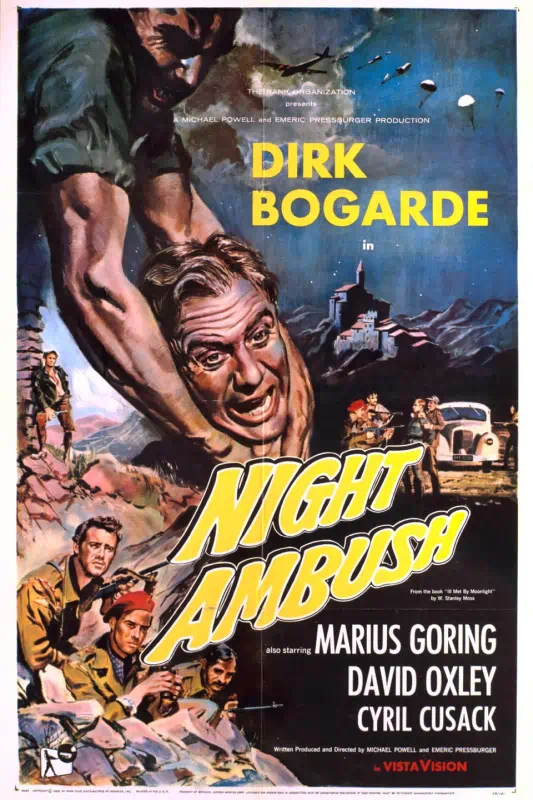

Moss’s book was adapted into a popular film, “Ill Met by Moonlight” (released as “Night Ambush” in the US), directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in 1957, starring Dirk Bogarde as Leigh Fermor.

Historical assessments continue to analyze the operation’s execution, impact, and ethical dimensions. A remarkable postscript occurred in 1972 when General Kreipe was reunited with his former captors, including Leigh Fermor, Moss, and several Cretan participants, on a Greek television show, providing a unique moment of reconciliation years after the conflict. Kreipe, who had been treated relatively well as a prisoner of war in Canada and Wales before his release in 1947, reportedly described his treatment during the abduction itself as being “like a knight, with chivalry”. He passed away in Germany in 1976.

Conclusion

Operation Landmark, the abduction of General Heinrich Kreipe from occupied Crete in April-May 1944, stands as a remarkable episode in the history of World War II special operations and resistance. Conceived initially to target the notoriously brutal General Müller, the mission adapted to capture his replacement, Kreipe, shifting its primary objective from punitive action to a bold demonstration of Allied and Cretan capability.

The operation’s success hinged on meticulous planning, audacious execution, and, most critically, the unwavering support and courage of the Cretan resistance network. From providing vital intelligence and logistical support, including the German uniforms essential for the initial ambush, to guiding the escape party through treacherous mountain terrain for nearly three weeks while evading a massive German manhunt, the contribution of Cretan civilians and fighters was indispensable. Their willingness to risk extreme German reprisals underscores the depth of their commitment to resisting the occupation.

The abduction delivered a significant blow to German morale and prestige on the island, serving as a powerful symbol of defiance and boosting the spirits of the Cretan resistance and the Allied cause. However, this symbolic victory was overshadowed by the horrific German reprisals that followed several months later under the command of the returned General Müller. The razing of Anogeia and the massacres in the Kedros/Amari region stand as tragic testaments to the brutal reality of Nazi occupation policy and the terrible price paid by civilians caught in the conflict.

Operation Landmark thus encapsulates the complex dynamics of resistance warfare: the daring and ingenuity required for successful operations, the critical importance of collaboration between external forces like SOE and local populations, the potent value of symbolic victories, and the devastating potential for enemy reprisals. Remembered through memorials, personal accounts like “Ill Met by Moonlight” and “Abducting a General,” and film, the Kreipe abduction continues to be studied not only as a feat of arms but also as a case study in the strategic calculations and profound human costs of irregular warfare in occupied territories. Its legacy endures in Crete as a symbol of resistance and in military history as an example of audacious special operations planning and execution, forever linked to the courage of the British officers and their indispensable Cretan allies.